Learning And Memory In The Classroom: What Teachers Should Know (Especially After The Summer)

Learning and memory are cognitive functions integral to the learning process. Without an understanding of learning and memory, too often we are wont to stare at our class in September wondering what has happened to everything they were taught the previous year.

Former headteacher Clare Sealy is well known for her clarity in explaining many of the complexities of cognitive neuroscience as it applies to the primary school educator.

Here she looks at memory formation and working in the classroom, alongside the science of forgetting. She also provides some guidance on how to best support your pupils and their academic progress.

As teachers continue to feel the impacts of Covid-19 and school closures on pupil knowledge and progress, this advice continues to be ever more relevant.

The Ultimate Guide to Effective Maths Interventions

Find out how to plan, manage, and teach 1-to-1 Maths interventions to raise attainment in your students. Includes a 20 point checklist for improvement.

Download Free Now!Summer brain drain is real…

It’s definitely a tough one. Imagine this: It’s the start of term, and you feel well-prepared for your new class.

The summer break saw you meticulously studying their assessment data; you know which objectives the children understood last year.

You are ready to hit the ground running this academic year by building on what they already know. So, you plan a range of interesting and challenging classroom activities to facilitate this, propped up by teaching strategies you’ve carefully woven through them.

Yet a couple of maths lessons in, it is apparent that those green boxes on your tracker system are lying …

Your pupils cannot do the maths you’ve planned, and some deny all knowledge of the concept.

Percentages? Never heard of them!

Division? What’s that?

Even those children who’ve kept themselves busy with plenty of summer activities (or even summer schools) might seem to have lost some of their learning, with maths skills and concepts often more ‘leaky’ than writing or reading skills.

Your carefully planned strategies have become pointless because pupils just can’t engage with the material.

There’s no alternative: scrap those lessons you lovingly crafted during your well-earned break, and go right back to basics.

Why do children forget their learning over the summer months?

Many potential reasons might occur to you for why this has occurred. Maybe their previous teacher’s assessment was more generous than the evidence strictly warranted.

Have over optimistic colleagues ticked boxes that a more sober analysis would have left empty?

It is only human to want to feel effective as a teacher, and it can certainly be tempting to blame the situation on your predecessor.

But think for a moment about the class you have just said goodbye to – is their new teacher secretly cursing your misplaced generosity too?

You know that the data you passed on was robust. Yet maybe they are just as baffled about the gap between reported academic skill and the ability of the children sat in front of them as you are.

Maybe, these memory failures are a result of human learning and working memory ability, and how these skills and information were initially encoded in pupils’ memories.

After all this, you are left wondering how on earth you’ll beat this summer ‘brain drain’.

The rest of this article looks at some of the findings into human memory and how memory encoding takes place so that we are better prepared to address the summer slide next time it comes around.

We’re not so much interested in which brain regions or cerebellum this takes place or how the brain systems of neurons and synapses function. Instead, we focus on what happens to memory performance and share some useful advice for teachers that you won’t need a psychiatry degree to implement.

What is working memory?

Working memory is an executive function that allows the brain to hold information temporarily. It has a limited capacity, meaning it can only retain limited pieces of information and only for short periods of time.

Working memory plays an important role in the process of learning (Gathercole, 2004). It is how we store, organise and interleave the information and skills needed to complete any calculation in the maths classroom, or reading or writing during literacy.

It’s for this reason poor working memory can result in working memory overload, where children cannot effectively store and manipulate the information required to complete a task. All children can benefit from working memory training but it can be especially useful for children with learning difficulties, dyslexia, and ADHD who more often face working memory difficulties and deficits.

Working memory is also an essential part of the journey to encode key information in long-term memory.

The importance of long-term memory

There is a reason the summer slide all too familiar situation occurs year after year. A child may well have demonstrated an understanding of a skill at one time, but being taught a new skill and successfully completing it once is only the beginning.

How to learn maths by having that concept securely stored in a child’s long-term memory – in a form where it can be used flexibly and adaptively – is the ultimate goal. Unsurprisingly though, the journey from A to B can be really tough.

It is really worth teachers understanding the journey of a concept to longterm memory, for two reasons:

- to ensure we provide the right enhancement to enable a child’s knowledge to reach its ultimate destination.

- to prime us to be alert for the pitfalls along the way and how we can mitigate against them.

Problems of working memory in the classroom and transferral to long-term memory

The journey to encoding a concept from working memory to long term memory, and creating secure retention, is fraught with obstacles. Understanding working memory capacity, and how it can affect memory process and memory storage is key to being able to support children.

1. Thinking about the wrong things

Our brains have to be selective; if we remembered everything going on at every moment we would become overwhelmed. The brain has evolved to prioritise the things we pay close attention to.

Therefore, it’s important to avoid planning lessons where a child’s focus is on the medium rather than the concept.

Playing maths games can be a great way to aid learning. However, the working memory demands of games include not only the mathematical skills and knowledge but also the rules of the games.

As a result, the brain may prioritise the rules and decide that the mathematical skills are not that important – and thus won’t remember them.

Open-ended maths problems can be similar. Problem solving requires pupils to use much of their working memory capacity on strategies, leaving less available to attend to maths.

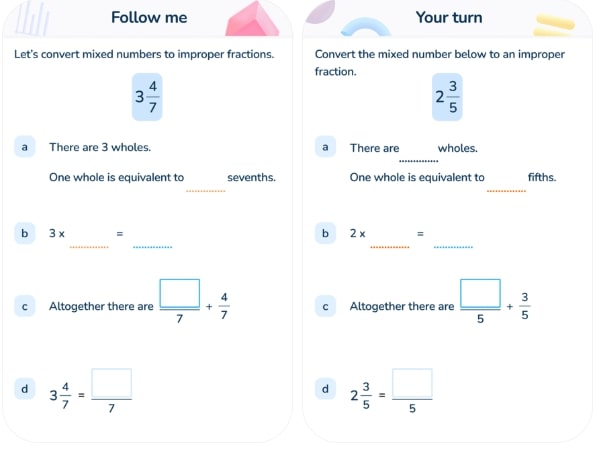

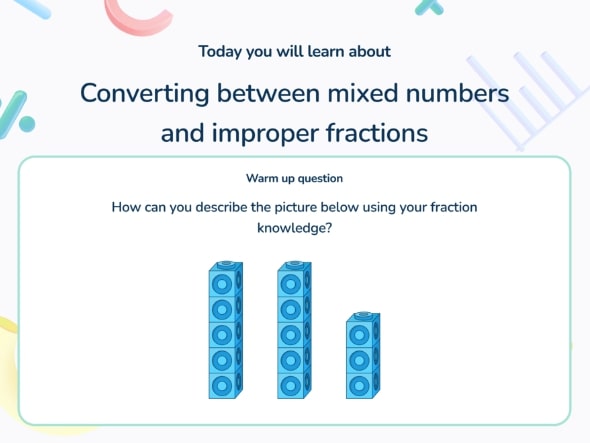

In Third Space Learning’s interventions, pupils begin with explicit instruction of the key skills required for the lesson and move on to problem solving only once pupils are secure in their understanding. We further support pupils from guided practice to more independent practice with worked examples and breaking down complex problem solving questions into easier chunks.

Goal-free problems can be an invaluable tool, but if used too early in the learning process (and especially without the requisite thinking skills), they are unlikely to result in long-term recall of the maths concepts we thought the children were practicing.

In contrast, if concepts are taught in a direct instruction method, it reduces the amount of information pupils must handle in their working memory and reduces the risk of cognitive overload.

Solution: plan learning activities with working memory loads in mind and ensure that they make students think about the right things.

Read more: Cognitive load theory and cognitive load theory in the classroom

2. Weak memory storage strength

Sometimes the memory can make it into the learner’s long-term memory but it isn’t a very strong memory yet.

The brain makes the pragmatic decision to let memories fade unless they get used. It will assume we only want to store long-term memories that we actively retrieve. A concept can make it into the learner’s long-term memory, but without regular use there will be no, or poor memory retrieval.

All teachers will have had that frustrating experience where a lesson appears to go very well, yet the next day the children appear to have remembered nothing.

The good news is – this is normal for the human brain and actually useful.

It sounds bizarre, but forgetting something is a necessary part of the journey from short term memory to long term memory.

The forgotten memory is not really forgotten; it is floating about somewhere in the long-term memory ready for activation, but needs to be retrieved in order to make itself stronger.

A rather counter-intuitive process, memory strengthening works best if the memory has been forgotten! For example: trying to remember new material a few minutes after a lesson will reap fewer dividends than trying to remember it the next day.

Testing before re-teaching

If children have forgotten a concept, the temptation is to boost memory by immediately re-teaching. However, this is not the best approach initially.

Although it seems mean and inefficient to make children struggle, what actually gets the memory juices flowing is that act of struggling (and maybe failing) to retrieve memories. This tells the brain ‘hey, I really want to remember this stuff!’

This is known as the ‘testing effect’ and has been very well researched. The best way to implement this is through small, frequent pop quizzes on a few concepts.

The worry with over-testing is that it is stressful for children. However, these are not intended as big, high stakes tests like SATs, and they can be planned purely for making learning stronger – not for collecting data.

Of course, once students have had an initial, possibly unsuccessful attempt at retrieving a memory, at that point the teacher should re-teach it and make use of memory aids, such as mnemonics to support children to memorise key information. This time, when it is remembered again, the memory will be stronger. That is why some schools start each maths lesson with a problem from the previous lesson.

In Third Space Learning’s one to one maths intervention, sessions start with warm up questions to activate prior knowledge to strengthen pupils’ memory and for tutors to diagnostically assess pupils before moving on to new content.

Additional reading: Clare has written a blog about retrieval practice in the classroom and how it can benefit pupils’ long-term memory. It is packed with useful tips and techniques that can be applied not only to stopping the summer slide but also to improving pupils’ recollection of information throughout the school year.

Optimising the process

Retrieving something once usually isn’t enough to build a strong, durable memory. Ideally, students should be asked to engage in deliberate practice of concepts at increasing intervals; a day later, a week later, a month later, 6 months later. This is the process of consolidation of a memory.

The brain gets the message: this stuff is important.

What makes these memories even stronger is if their recovery arrives out of the blue, in the middle of learning about something else.

For example, in the middle of a sequence of lessons about fractions, give pupils a few subtraction questions to work on.

This is effective because the brain has to think particularly hard when asked to retrieve something it wasn’t expecting to. Research has shown that when children engage in this ‘interleaved’ practice is more likely to result in strong memories. It is also a good idea to connect different mathematical concepts together. This can be done visually through mindmaps and number lines.

Solution: frequent low stakes quizzes at spaced out intervals that get children to try and retrieve what they have previously learned.

3. The “use it or lose it” principle

Memories fade with time if they are not used. Exceptionally keen students might do some summer reading, or practice their maths through the summer holidays, but most children won’t have done any mathematical thinking between July and September. Their memories will be starting to fade.

However, don’t despair! Memories might be fading but they are not gone forever. With a bit of prompting, they will be reawakened.

It is very unlikely that you will need to reteach the concepts in the same detail as when they were first learned.

It’s best to anticipate this hurdle at the start of the year. Expect to have to reanimate faded memories from previous year group content. Plan with the view that forgetting stuff is inevitable, and it ultimately results in stronger memories.

This is all part of the brain’s cognitive architecture and memory systems.

Solution: plan deliberately to revise previous learning. It will come back quickly.

4. The transferability trap – episodic and semantic memory

The goal of learning is that concepts are securely stored in the long-term memory. They must also be in a form where they can be used flexibly to solve all sorts of different problems; this is known as declarative memory or explicit memory. (This is in contrast to procedural or implicit memory for something like riding a bike the process for which can be difficult to actually articulate or ‘declare’.)

Yet we know that students find this hard.

Understanding how this declarative memory functions and the way the brain learns can help us plan for this inevitable eventuality.

There are two different sub-types of memory that correlate with each other here.

Episodic memory

Episodic memory is the autobiographical part of our memory that remembers the times, places and emotions that occur during events and experiences.

When we first learn concepts, we initially remember them using our episodic memory.

In the episodic memory, the sensory data – what a child saw, heard, felt and possibly smelt during a lesson – alongside their emotions and mental health, become part of the learning.

These emotional and sensory cues are triggered when we retrieve the stored information.

Cognitive overload can be reduced if children are sitting at the same desk in the same class with the same teacher, as this familiar backdrop is part of their memory alongside whatever it is they are learning.

Take away these environmental cues and the memory is suddenly hard to find.

Semantic memory

Semantic memory retains facts, concepts, meaning and knowledge that have been liberated from the emotional and spatial/temporal context in which they were first acquired.

This type of memory that is not so context-dependent and is the final destination on our learning journey.

Once a concept has been stored in the semantic memory, then it is more flexible and transferable between different contexts.

When a child changes classes and teachers, concepts in the episodic memory will be much harder to recall without those familiar environmental prompts.

The presence of an unfamiliar teacher will mean that the emotional context is also different. Both these changes make remembering stuff harder.

Episodic memories have sensory data anchoring them down to specific contexts. The next step is to set the memory free of their emotional and environmental cues. It’s important to anticipate this in teaching and planning.

Solution: be aware of the need for sensory cues and manage your expectations initially with a new class.

3 simple ways to boost brain activity and support children’s synaptic plasticity before and after the summer

1. Change the environment

Some changes can happen straight away. For example, making sure children are not always in the same seat will help. It is during June and July that you can most effectively plan for this, as this is when most concepts are revisited.

Ideally, plan to change the physical setting – maybe by doing some maths in the hall or in the playground, but at the very least by making sure children sit next to different peers.

This way, they will encounter episodically memorised topics without familiar environmental stimuli. This nudges the memory forward on its journey from episodic to semantic.

2. Change the context for learning

Another way to beat the summer slide is to apply the learning to a different part of the curriculum.

For example, DT is ideal for practicing measures outside of the confines of a maths lesson, whether it involves measuring lengths of wood or weighing ingredients for a recipe.

Art lessons can involve revising symmetry or fractions. Reinforce that half of a shape can be made many different ways by giving children two differently coloured pieces of paper the same size. Get the children to cut one piece in half and discard one of the two halves.

The remaining half can be cut into different shapes, and each piece stuck onto the other coloured shape. The resulting pattern will be half one colour, half the other, yet every child will have demonstrated this differently.

Art could also be used to revise ratio. Perhaps launch a class investigation into the effect on tone by adjusting the different proportions of white to red paint. Or, experiment with different amounts of sand and water to see which mixture makes the firmest sandcastle. Definitely one for outside!

If you are feeling really brave, you could revise angles by using a water pistol and a giant protractor! The investigation would test which angle works best if you want to hit a particular target.

Although this lesson has the potential to provide lots of distraction (to put it mildly), which can result in children paying attention to the wrong thing, it does have a great advantage: it involves children measuring angles vertically as opposed to horizontally.

By explicitly transferring the learning to a different context, we strengthen the conceptual understanding.

3. Build memory, not memories in maths (or any other subjects)

What is important to stress here is that exciting lessons take place once the children already know the maths, have stored it in their long-term memory and have the working memory skills to retrieve and manipulate them. The above suggestions are not great for learning the concept in the first place because they are so episodically rich.

The danger is what will grab the children’s attention span is the extraneous context and not the maths: The children will only remember the experience.

One might assume that because children remember plays, trips and sports days, the key to remembering maths is to make lessons full of exciting, memorable experiences.

While that is not an unreasonable supposition, it is based on a misconception about how memory works. If we over-stimulate the neural circuits with emotions by trying to build good memories, we actually work against the development of strong long-term recall of the concepts we were trying to teach.

Children must forget the episodic clutter surrounding how they learned something. If learning is too focused on the time, place and context, that memory will be inflexible and not very transferrable.

The key to strong semantic memories is lots and lots of thinking hard, practicing and revisiting concepts and then finally, applying them in other contexts to aid transfer.

If teachers understood more about cognition and how the brain remembers information and didn’t just leave it to the neuroscientists, it might save us a lot of frustration.

If you want children to remember things long term, you need to plan for it not just at the point of delivery, but throughout the coming year.

Further Reading:

- 20 Maths Strategies KS2 That Guarantee Progress for All Pupils

- Quality First Teaching Checklist: The 10 Most Effective Strategies For Primary Schools

- The Most Effective Teaching Strategies To Use In Your School: Evidence Based And Proven To Work

- Teaching ‘Lower Ability’ Students Maths: “Are We Bottom Set?”

- Summer maths activities and Holiday maths activities

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Every week Third Space Learning’s maths specialist tutors support thousands of students across hundreds of schools with weekly maths intervention programmes designed to plug gaps and boost progress.

Since 2013 these personalised one to one lessons have helped over 150,000 primary and secondary students become more confident, able mathematicians.

Learn about the scaffolded lesson content or request a personalised quote for your school to speak to us about your school’s needs and how we can help.