Ofsted Mathematics Subject Report: Coordinating Mathematical Success

There is a large gap between the lowest and highest achievers in maths in the UK, and between disadvantaged and advantaged students. Ofsted recently researched why this may be and maths teaching in primary and secondary schools in the UK. They published their findings in the latest mathematics subject report, “Coordinating Mathematical Success” in July 2023.

The report uses themes from their 2021 research review and looks at examples of stronger and weaker practice in 50 schools visited between September 2021 and November 2022.

It is a detailed and fairly lengthy document so this article aims to do a bit of the legwork for you by summarising the main themes and key points to reflect on to plan effectively for maths teaching in your context.

Ofsted maths report: Key takeaways

- There has been a positive shift in the quality of mathematics education at both primary and secondary over the last few years;

- Schools are increasingly using support of Maths Hubs and other professional networks to disseminate good practice;

- Recruitment and retention of specialists is recognised as a major issue, particularly at secondary level;

- Curriculum planning has improved considerably at both primary and secondary;

- There remains a concern around how much external examinations or accountability measures are affecting curriculum decisions, particularly Year 6 key-stage tests at primary and GCSEs in KS4.

Ofsted Maths Fact File

Find out how to prepare for your Ofsted maths inspection. Written by experienced school leaders and former Ofsted inspectors, this guide will help you and your team to prepare.

Download Free Now!Keep reading to learn more about what Ofsted says about these key areas of teaching mathematics:

Curriculum

Curriculum intent

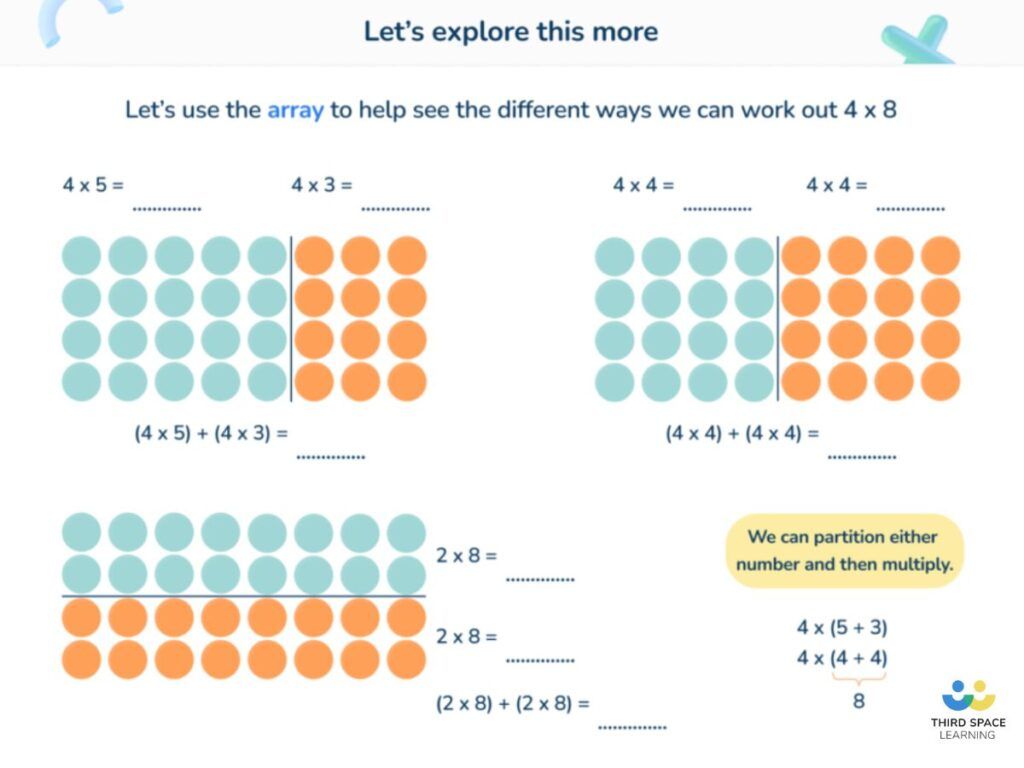

Drawing on Ofsted’s maths review, the report states that the curriculum should “identify and sequence, in small steps, declarative, procedural and conditional knowledge, and plan for pupils to learn this in small steps”.

The report underlines the importance that curriculums “emphasise secure learning” of mathematical knowledge, rather than aiming for content coverage or simply encountering the topics.

At the primary level, many schools used curricula that sequenced learning in small steps including ‘buffer zones’, also known as ‘consolidation blocks’, to allow more time to respond to needs of individual pupils. The report views the use of commercial schemes positively where these are used to reduce teachers’ planning workload.

Curriculum sequencing at primary was mentioned as an area for improvement in some schools. For example, the report is critical of the practice of leaving Geometry until the summer term which results in long gaps before revisiting this key knowledge each year. The report also notes that Geometry topics were occasionally left out of in-house assessments.

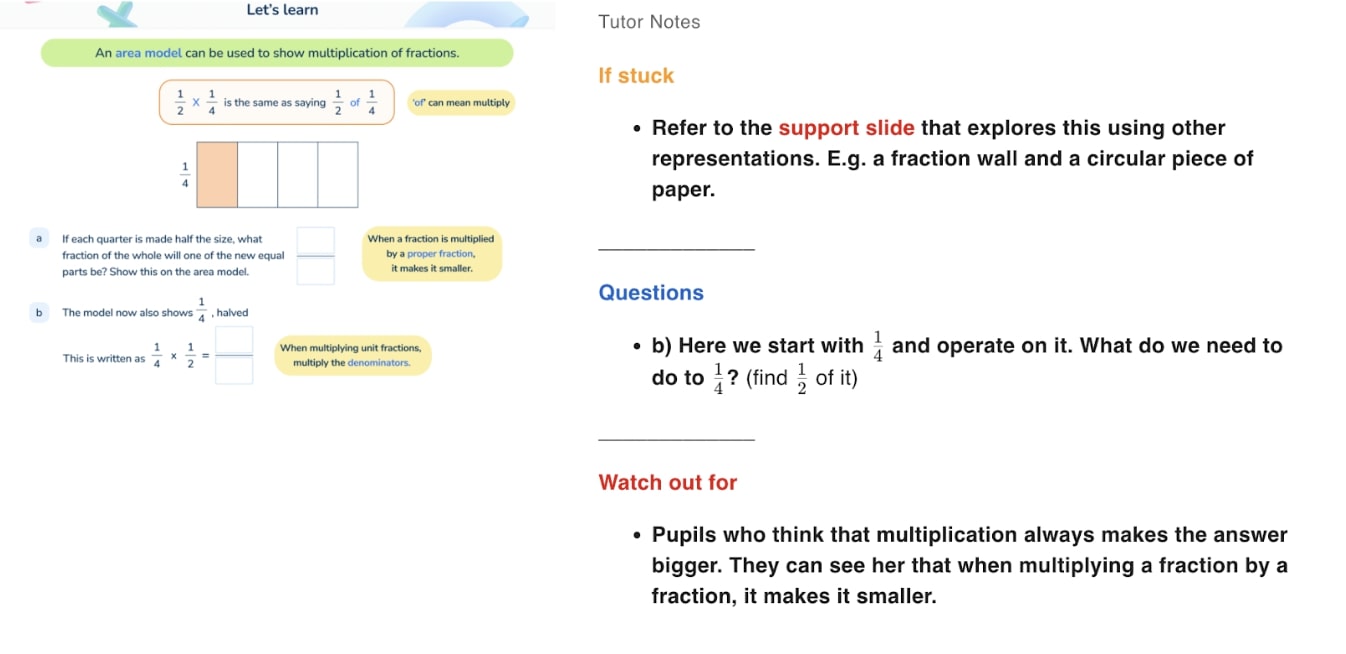

The one to one nature of Third Space Learning’s online maths tutoring allows for completely personalised delivery and aims to meet pupils wherever they are. Tutors have access to support slides and resources designed by former teachers and pedagogy experts to support pupils as and when they need it.

Our ready to go lesson slides for whole class teaching are block based lessons that support curriculum sequencing. They also include support slides that teachers can use as pre-teaching or support within the lesson.

Third Space Learning delivers personalised maths tutoring to support pupils to tackle the topics they need help with most. Our initial diagnostic and ongoing assessment identifies learning gaps and misconceptions to address them early and as they emerge – not leaving them to widen until the topic is covered in the curriculum once again.

At secondary school, just over half of schools visited had a 5-year programme with no distinction between KS3 and KS4. The report appears critical of other splits due to content either being rushed or repeated.

The report discusses the impact of GCSE examinations on KS4 curriculum planning in detail. Ofsted suggests that tiering decisions are generally being made too early, and that, in some cases, this reduces mathematics “to an exercise in preparing pupils to pass an external examination and does not provide pupils with a rich mathematical education”. The report acknowledges that external pressures and accountability measures are driving this narrowing of the curriculum.

In our GCSE revision programme, whilst we foreground preparing students for exams, we continue to build in opportunities for scaffolding, extension and challenge where needed to provide pupils with a rich learning experience and a secure understanding of key concepts.

Recommendations

- Ensure your curriculum engenders secure learning of mathematical knowledge, as opposed to simply covering the required content;

- Consider curriculum sequencing so that concepts and topics are revisited in a timely manner, rather than blocking content in terms (particularly Primary);

- Ensure that external examinations are not the main focus of curriculum intent and design, particularly in Years 6, 10 and 11.

Problem-solving

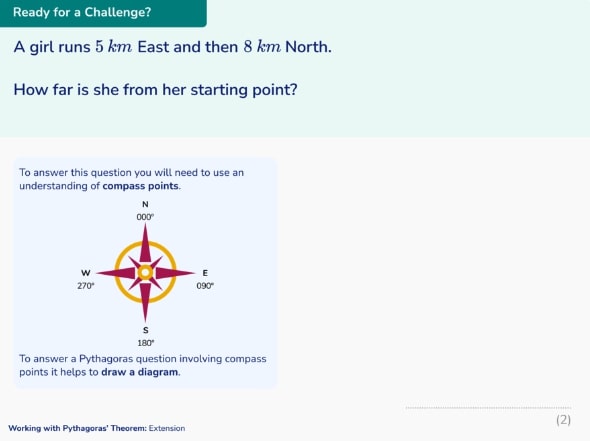

Ofsted describes problem-solving strategies as a taught combination of declarative and procedural knowledge. The research review indicates that pupils cannot “become problem-solvers by imitating the activities of experts” and that strategies to solve problems should be explicitly taught. The report highlights problem-solving as an area for development, both in primary and secondary schools.

At primary school, some pupils were given problem-solving as an activity choice – this meant that some skipped fluency practice, leading to issues in further study. Other pupils could choose to opt out of problem-solving work altogether. Ofsted discuss a lack of conditional knowledge (i.e. knowing when and why to apply declarative and procedural knowledge) as being a major stumbling block for solving problems.

Need support with problem solving at primary? See our blogs and resources:

- Maths Problem Solving: Engaging Your Students And Strengthening Their Mathematical Skills

- Fluency Reasoning and Problem Solving

- The Ultimate Guide to Problem Solving Techniques

At secondary school, the Ofsted maths report highlights a lack of whole-department planning of problem-solving, with the selection of problems and approaches to teaching problem-solving often left to individual teachers. The report notes that this often disproportionately affects pupils in lower sets or in sets with a less experienced teacher.

In some schools, problem-solving was addressed within the final few questions of “a predominantly procedure-focused exercise” – the report notes that many pupils did not progress onto these final questions, and therefore had limited opportunity to learn problem-solving skills.

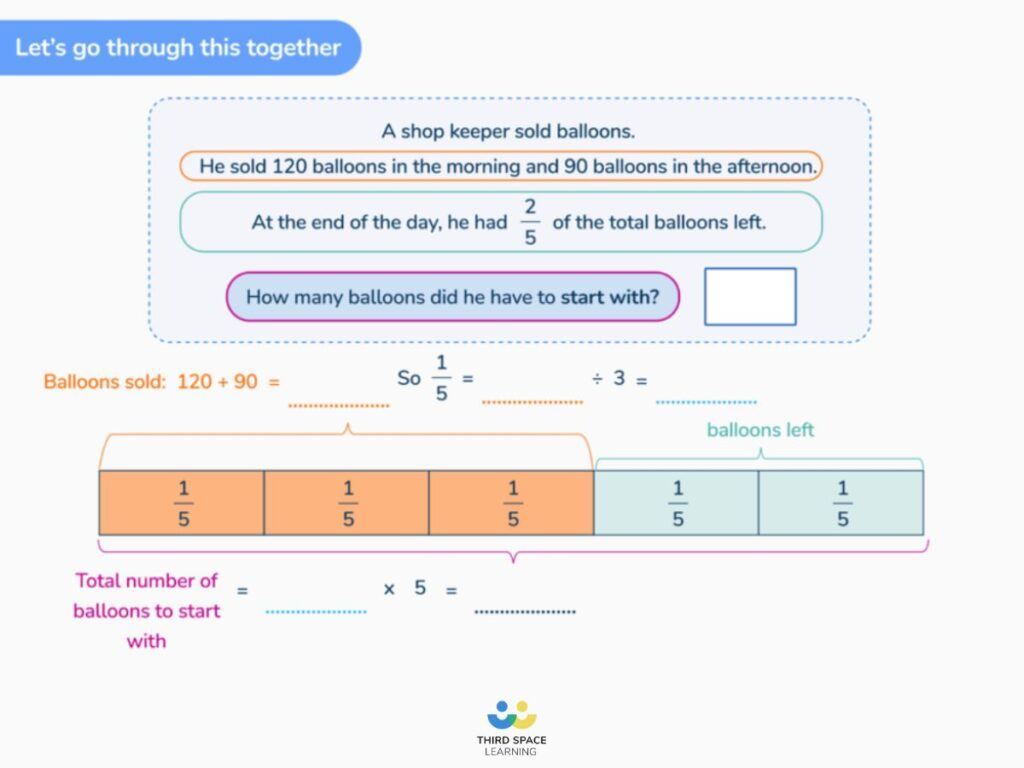

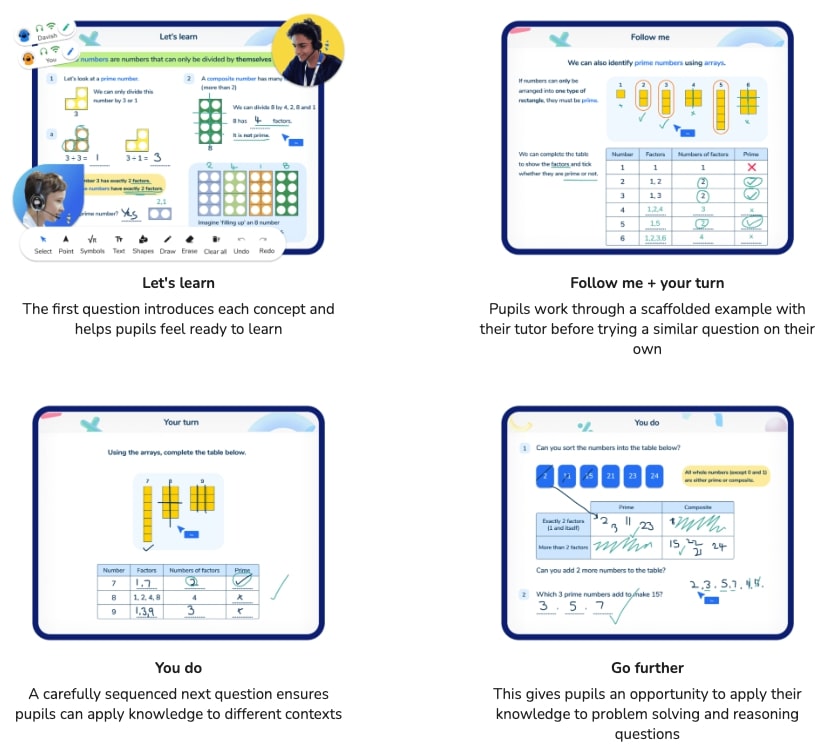

In order to support students to progress from procedural knowledge to practising questions that involve a variety of skills, our lessons break down complex problems into their constituent parts. Our specialist tutors then carefully scaffold learning to build students’ confidence in key skills before combining them to tackle problem solving questions.

Our free GCSE worksheets have similarly been carefully structured. Each worksheet begins by building fluency through quality practice. The next section is a series of applied questions in a variety of contexts, often combining the focus topic with others. This supports teachers when planning to integrate important problem solving skills throughout the curriculum.

Recommendations:

- Ensure all pupils have sufficient opportunity to access problem-solving work

- Include explicit planning of problem-solving in curriculum development and documents

Reception

The report refers to Reception provision frequently and identifies planning in Reception as an area for improvement. Rather than using early learning goals for curriculum planning (as seen in some schools), the report states that planning should be “as detailed as” the planning for older years.

Furthermore, while activities at Reception level were generally well-planned, pupils could often select which activity to participate in, leading to some pupils getting significantly more mathematical practice than others.

It is suggested that, in some schools, this lack of detail in Reception is partly responsible for a widening attainment gap as pupils move up the school. For example, pupils who cannot easily subitise or recall addition facts may be able to mask these difficulties in Years 2 or 3 by using finger counting. However, this inability to work efficiently becomes more apparent as pupils reach Year 6, leading to a need for intervention at this stage.

If you’re looking to support a secure understanding of numbers in your young pupils, try out our Maths Memory Cards Numbers to 20. The cards show the numbers between 1 and 20 using words and concrete resources. These can be used to help recall or used together to make addition and subtraction number sentences.

Recommendations

- Identify and sequence small steps in the Reception Year curriculum;

- Ensure that all pupils are secure with fundamental knowledge such as subitisation and addition facts.

Pedagogy and assessment

Teaching

At KS1 and KS2, teachers generally showed strong subject teaching knowledge, using small steps and careful explanations. The report attributes this to increased use of networks of support, such as Maths Hubs.

Simple models, such as bar modelling, were used to develop understanding with pupils moving from concrete to pictorial to abstract representations as appropriate. In some cases, teachers used too many concrete or pictorial demonstrations, leading to confusion.

Questioning was generally used well, but the report highlights that, in a minority of cases, questioning required pupils to “second-guess” rather than understand and learn new knowledge. Learn more about effective questioning in the classroom here.

At secondary school, most teachers used correct mathematical terminology and modelled careful presentation of work. In some schools, inaccurate mathematics was modelled and then copied by pupils; this was ascribed to lack of subject specialist knowledge.

The choice and selection of methods at secondary is also discussed in some detail. Where method selection is deliberate and done as a result of pedagogical discussion, it is effective in helping pupils to understand new concepts. On the other hand, sometimes the methods chosen only applied to the specific situation that pupils were currently experiencing, limiting their ability to transfer this knowledge to future learning.

In some cases, the pressure of high-stakes accountability of examinations led to teachers using tricks or quick fixes, leading pupils to view mathematics as “a list of unconnected methods to remember and apply”.

Mathematical understanding is at the heart of our programme design. At Third Space Learning, all of our lessons and resources are created by our team of expert mathematics teachers. We combine the decades of specialist knowledge of our team with the latest educational research to ensure that our lessons, tutor training and resources are comprehensive and adaptable.

Recommendations

- Carefully select appropriate concrete or pictorial representations to enhance explanations – an excess of different representations may cause confusion;

- Ensure questions do not just require pupils to “second-guess” an answer;

- Use and model correct mathematical terminology and presentation – at secondary in particular, non-specialists may require support with this;

- Ensure that mathematics is not taught as a list of tricks or methods to remember.

Practice

The report outlines two types of mathematical practice:

- Type 1 – retrieving and rehearsing facts, methods and strategies

- Type 2 – explore and explain relationships, prove understanding and describe reasoning

In the primary schools, pupils were given increased opportunities to practise new material, including overlearning – the report describes this as a “very positive” step. This practice included songs, rhymes and choral response, drawing on effective strategies from phonics approaches.

In some cases, some pupils moved on too quickly from Type 1 practice. This was particularly when they were allowed to choose their own activities. On the other hand, some pupils did not tackle any problem-solving questions or activities.

In the secondary schools, pupils had the opportunity to practise new content in lessons, but in some cases, this practice did not become more complex over time. The report also notes that, as in primary, some pupils did very limited or no practice on “Type 2” problems.

In order to deepen pupils’ understanding of key concepts, Third Space Learning’s lessons are broken down into 4 stages, encouraging students to move from guided to independent practice. When applying learning to problem solving questions, pupils are encouraged to try the question independently, with appropriate support given as and when it is needed.

You can build reasoning and problem solving skills into your classroom teaching through our resource, Rapid Reasoning. This resource is designed to be used in conjunction with daily arithmetic practice to expose all pupils to problem solving.

Recommendations

- Ensure that all pupils have sufficient time to practise Type 1 problems to automaticity;

- Ensure that all pupils access Type 2 problems (reasoning and problem-solving), rather than just those who get to the end of the exercise.

Retrieval

In the primary schools, teachers consistently built in retrieval practice, including starting lessons with a “fluent in five” approach and adding another short practice session during the afternoon or during morning registration. Songs and rhymes were also mentioned as a valuable way to lead retrieval practice sessions with younger pupils.

At secondary, retrieval practice was effective when used for its primary aim: “to embed previously learned knowledge more deeply in long-term memory”.

In some schools, gaps or misconceptions occurring during retrieval practice exercises were not identified or dealt with, leading to misconceptions becoming embedded. There was very little problem-solving integrated into retrieval practice – spaced practice could include structural similar problems from previous work.

Our popular Fluent in Five resource provides students with the opportunity to practise key skills each day, five days a week for every week in every term of the academic year.

At primary, Fluent in Five follows the White Rose Curriculum and is focused on arithmetic skills. At secondary school, Fluent in Five focuses on key skills that have been carefully mapped over Years 7, 8 and 9 and at GCSE Foundation level.

PowerPoints and worksheets are provided to provide teachers with flexibility over how to use the questions during a form period, lesson or as part of a homework task.

My class has particularly benefited from Fluent in Five – they enjoy the daily challenge (which we do to funky music) and I have seen very good progress in their arithmetic fluency.

Year 6 Teacher, Oxfordshire

Recommendations:

- Build in consistent retrieval practice sessions, thinking creatively about where time could be used in the school day;

- Ensure that any misconceptions arising from retrieval practice are addressed and do not become embedded through repetition.

Identifying gaps

Many primary schools used a combination of live marking, whole-class feedback and same-day intervention to respond to individual pupils’ needs. This strong practice meant that errors and misconceptions were identified early, minimising later workload for teachers.

In Third Space Learning’s tutoring, our tutors are trained to identify and understand common errors and misconceptions in lessons. Our programme designers include notes and tips in every lesson for tutors to refer to throughout the lesson.

Pupils at primary school enjoyed low-stakes testing when presented in a competitive, fun way, and talked about these positively.

At secondary school, many schools reported that gaps in prior knowledge were addressed before beginning a new topic but in practice this was not done consistently.

Teachers should also think carefully about the best way to address gaps or misconceptions – the report gives an example of weaker practice where the example and explanation given increased misconceptions. The suggestion is that a better approach would be to carefully plan and then revisit the identified gap in a subsequent lesson.

We support teachers at secondary schools to identify and address misconceptions in a range of GCSE maths topics through our Diagnostic Questions resources.

Each diagnostic question has four answers to choose from: one correct answer and three answers that each highlight a different misconception. The detailed answer sheets help students to understand not only why the correct answer is correct, but also how each of the common misconceptions can be avoided.

Recommendations:

- Live marking and same-day intervention are particularly effective strategies at primary level;

- Investing resources in addressing misconceptions as they occur saves time and workload in the long run;

- At secondary, misconceptions should be addressed carefully to ensure these are not compounded;

- Non-specialists or less experienced may not be able to respond immediately to misconceptions as they arise – in this case it is more effective to plan how to address the identified gap and revisit at a later date.

Summative assessment

Many primary schools used end-of-unit tests to assess pupils’ progress. Strong practice included setting a proficiency benchmark at 80% (rather than the 50% of ‘age related expectations’ on end of key stage tests) and using multiple choice questions to expose misconceptions.

The report highlights issues with using QLA at the end of key stage tests, as this does not “accurately pinpoint gaps in […] component knowledge”. Furthermore, the benchmark of 50% accuracy does not adequately prepare pupils for KS3.

At secondary school, many schools use termly or half-termly timed tests to assess whether curriculum goals have been achieved. Grades or other thresholds for performance were usually given, but generally there was little concern about gaps in pupil knowledge identified from these tests. Identifying pupils for intervention who were “behind target” according to progress tracking often missed other pupils with very similar mathematical needs who also needed support.

Using tests which include material that pupils have not covered (e.g. use of full GCSE papers in key stage 3) is an inefficient use of time and could impact on pupil confidence.

Recommendations:

- Consider the benchmarks used on summative assessments – for example, at primary the benchmark 50% for “age related expectations” may not be appropriate when measuring proficiency;

- Ensure gaps identified on summative assessments are addressed with all pupils;

- Avoid using tests which include material that pupils have not covered.

The impact of external examinations

The report is critical of the extent to which external examinations drive pupils’ experiences of mathematics, particularly in Year 6 of primary and in the latter years of secondary school.

It is positive to see that Ofsted appears to recognise that this is often beyond the control of teachers and leaders, and occurs as a result of accountability measures and external pressures. The report calls for the DfE, Ofqual and Awarding bodies to explore whether the design of the current mathematics GCSE contributes negatively to practices in schools.

Systems and organisation

Timetabling, resource allocation and subject specialists

In primary schools, the report discusses a common pattern of more teaching resources and time allocated to later years, particularly Year 6. This is often to the detriment of pupils lower down the school, and stronger practice would be allocating additional resources to closing gaps with the youngest pupils as they occur, rather than waiting until the gaps widen later on.

At secondary school, the norm was around 3.5-4 hours of maths teaching per week, mostly over three or four days. In some cases, this was over two longer lessons per week. Year 11 is generally allocated more curriculum time than KS3 classes.

All schools visited had split classes, due either to timetabling constraints or to ensure that no classes were taught entirely by non-specialists. Split classes were more likely to occur in Year 7, or in lower sets in other year groups.

The report acknowledges the wider picture of issues with recruitment and retention of specialist mathematics teachers. It also identifies the strong practice of supporting non-specialist teachers with additional CPD, close work with other departmental members, and use of comprehensive in-house curriculum planning.

At both primary and secondary levels, Ofsted recommends that teaching assistants and other adults working with pupils need a “secure knowledge of the […] curriculum and […] pedagogical approaches”. This can be accomplished by assigning a TA to work mainly with the mathematics department, and provide subject-specific CPD. In schools where TAs had less subject specific knowledge, explanations and assistance were more generic, and in some cases, increased the number of misconceptions or did not support pupil progress.

In the UK, maths subject specialists in education are in short supply and the country has failed to meet recruitment targets for several years. Third Space Learning offers a scalable programme that taps into the global talent pool to recruit maths specialists who we train as tutors through an intensive initial tutor training programme and ongoing CPD.

We also have a range of resources and development videos available on our Maths Hub to support your non-specialist staff to brush up their knowledge. You can also see our many blogs that break down key concepts in maths and education:

Recommendations

- Consider allocating additional resources earlier on in pupils’ education, rather than waiting until gaps have widened later on up the school;

- Ensure that non-specialist staff are supported through CPD and close work with other department or team members;

- At secondary, consider allocation of a “specialist” maths TA who works primarily with the maths department.

Setting

In primary schools, most classes are mixed-attainment. If setting occurs, this tends to be in Year 6 (and occasionally in Year 2). The report suggests that this indicates that “despite strong curriculums and teaching, not all pupils are making good progress”. They highlight that a better use of these additional resources would be in significant intervention with younger pupils to address gaps and misconceptions when they first occur.

At secondary, all schools used setting or streaming by attainment at some stage. Mixed ability groups were more common in Year 7, with many schools stating that this was a temporary response as a result of pandemic disruption and lack of KS2 assessment.

CPD, Maths Hubs and department time

At the primary school level, the report mentions improvements in collaboration between schools via Maths Hubs, academy trusts and other more informal groups.

CPD from Maths Hubs and the NCETM have helped to inform leaders about high-quality mathematics teaching, and this has been disseminated via school staff meetings. There is some evidence that lesson observations at primary schools are becoming more low-stakes, with focus on improving quality of teaching and learning, rather than accountability. However, the report highlights that observations should, where possible, focus on pupils and their learning rather than “a checklist of observable features of teaching”.

At secondary school, the report praises the “significant move from […] administration activities to […] an opportunity to think about effective teaching”. Strong CPD was department-led, and focused specifically on effective teaching of mathematics; whole-school generic provision on themes is less likely to be effective.

Recommendations

- Ensure lesson observations focus on pupils and their learning, rather than observable features of teaching;

- Use department or team time to focus on effective teaching of mathematics, rather than more generic provision.

Culture

At primary school, the report praises a positive mathematical culture in many primary schools. Pupils are given opportunities to take part in “friendly competition” via online platforms, and encourage a culture where it is OK to make mistakes.

You can find ideas and downloadable resources for maths games and activities for your classroom here.

The report also discusses the positive use of songs and rhymes at primary to assist with retrieval and practice of important knowledge, such as times table facts or counting. This creates “a culture in which mathematics is celebrated”.

Useful information to support pupils in their mathematical learning was often shared with parents and carers.

Recommendations:

- Encourage a positive culture where it’s OK to make mistakes;

- Share information with parents and carers to support pupils in their mathematical learning.

Conclusion

Ofsted paints a broadly positive picture of maths education in the UK in both primary and secondary schools. It is in great contrast to Ofsted’s 2012 report, Made to Measure, which called on schools to urgently take action to improve maths teaching and learning. This is testament to the effective planning by SLT and Maths Leads and the commitment of teaching staff across the country.

Despite improvements, there remains a large gap between the highest and lowest achievers and between advantaged and disadvantaged learners. This suggests that there remains opportunities for schools to reflect on their approaches and learn from stronger practice in order to ensure that all pupils experience consistently good mathematics teaching.

It’s our mission at Third Space Learning to provide support to teachers and learners to reach this goal through our affordable online one to one maths tutoring and our range of downloadable teaching resources. Learn more about our tutoring programmes and how your schools can use the National Tutoring Programme to fund your in-school tuition.

More reading and resources:

- Ofsted’s Primary Maths Framework: Applying The EIF

- What to Do When You Get ‘The Call’ for an Ofsted Inspection

- A document about Third Space Learning for your school to share with Ofsted during an inspection

Important links

Gov.uk | Research review series: mathematics

Gov.uk | Coordinating mathematical success: the mathematics subject report

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Every week Third Space Learning’s specialist school tutors support thousands of students across hundreds of schools with weekly online 1 to 1 maths lessons designed to plug gaps and boost progress.

Since 2013 these personalised one to one lessons have helped over 150,000 primary and secondary students become more confident, able mathematicians.

Learn how the tutoring integrates with your SEF and Ofsted planning or request a personalised quote for your school to speak to us about your school’s needs and how we can help.

![The 12 Most Important Ofsted Safeguarding Questions and Answers [2024]](https://thirdspacelearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/safeguarding-questions-and-answers-1-180x160.jpg)