How The New No Marking Policy For Our Primary School Works

The previous heavy-duty marking policy wasn’t working at St Matthias Primary school so headteacher Clare Sealy decided to start from scratch with a new no marking policy for her primary school.

Read this earlier blog first to find out more about Clare’s research into what constitutes ineffective and effective marking in primary school.

How we set about creating our no marking policy

For us, it seemed important to differentiate the marking approaches we would use for different subjects – and then to a degree, with phases of the school. The marking and feedback policy that might work for KS2 Maths would not be the same as for KS1 Literacy.

What follows are some of the principles that underpin our no marking policy and then how these principles work in practice in Maths and English. As you’ll see the focus is very much on actionable feedback that children can taken into the next activity or the next lesson.

Ofsted Preparation Guides

Prepare for your next inspection with this step-by-step maths framework. Includes checklists and questions that Ofsted have asked during visits to other schools.

Download Free Now!Key principles of the St Matthias Primary School marking and feedback policy

These principles are taken from the marking and feedback policy on the St Matthias Primary School website.

- The sole focus of feedback should be to further children’s learning;

- Evidence of feedback is incidental to the process; we do not provide additional evidence for external verification;

- Feedback should empower children to take responsibility for improving their own work; it should not take away from this responsibility by adults doing the hard thinking work for the pupil.

- Written comments should only be used as a last resort for the very few children who otherwise are unable to locate their own errors, even after guided modelling by the teacher.

- Children should receive feedback either within the lesson itself or it in the next appropriate lesson.

- The ‘next step’ is usually the next lesson.

- Feedback is a part of the school’s wider assessment processes which aim to provide an appropriate level of challenge to pupils in lessons, allowing them to make good progress.

- New learning is fragile and usually forgotten unless explicit steps are taken over time to revisit and refresh learning. Teachers should be wary of assuming that children have securely learnt material based on evidence drawn close to the point of teaching it.

- Therefore, teachers will need to get feedback at some distance from the original teaching input when assessing if learning is now secure.

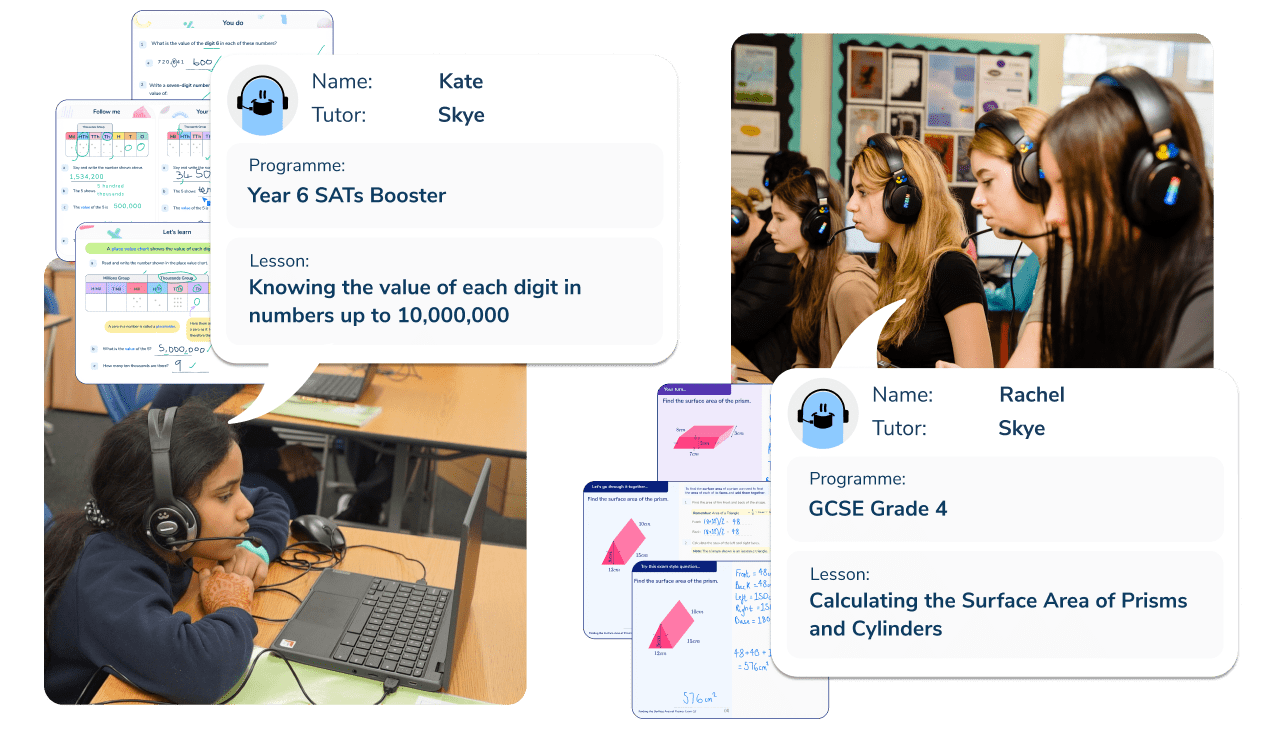

Meet Skye, the voice-based AI tutor making maths success possible for every student.

Built by teachers and maths experts, Skye uses the same pedagogy, curriculum and lesson structure as our traditional tutoring.

But, with more flexibility and a lower cost, schools can scale online maths tutoring to support every student who needs it.

Watch Skye in actionMarking policy approaches for maths

1. Pupils self-check their maths work

With our new system, Maths teachers now have answers to problems available. This means that, after four or five calculations, pupils can check their answers themselves. That way, if they have a misconception or misunderstand something they can alert the teacher immediately.

This avoids the situation where a child has diligently worked through reams of sums, as the class teacher works with a group, but has done entirely the wrong thing. This is worse still if it happens with a whole group.

Self-checking means that mistakes are realised ten minutes into the lesson, rather than at the end. It’s so much better for the pupils.

This approach also has the benefit of improving pupils’ confidence. We usually produce work at three levels of challenge. Pupils choose which level of challenge to start at and, naturally, less confident (but able) children usually start at the easiest level.

However, the new approach lets these pupils see when they get the first few calculations correct. Inevitably this helps them feel more confident and more willing to move on to the next level.

It also helps improve peer marking. For example, when more confident pupils finish their work with time to spare, they can consolidate their learning by ‘marking’ other children’s books. Crucially, those pupils actually have to do the calculations again – faster and possibly mentally – rather than just ‘checking’ against their own answers.

All this places the onus on the learner to check their work and identify their own errors which is fantastic for their learning. But like anything, pupils must be taught how to do this.

2. Teach pupils the skills of self-checking

Teaching self-checking involves teaching pupils to think deeply about the work they have just learnt. Otherwise, they might just scan through their work, reading but not really thinking.

When you think deeply about something, it is much more likely to get stored in your long term memory. As Daniel Willingham says ‘memory is the residue of thought.’ To get pupils thinking about their work, we sometimes use a visualiser to model ways of checking (as an alternative to providing answers). We expect pupils to do the same.

For example, pupils might repeat a calculation in a different coloured pen and check they’ve got the same answer. Here, we remind them that for addition calculations involving more than two numbers, adding the numbers in a different order is an even better way of checking.

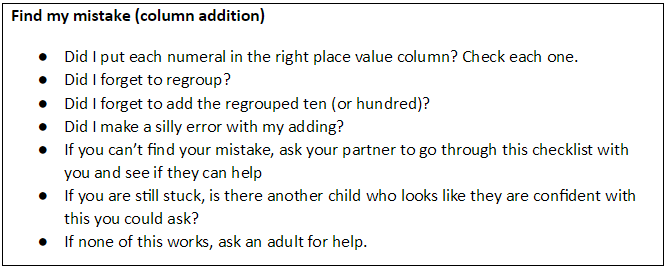

3. Provide marking prompt sheets for children

We also provide prompt sheets to help pupils who are struggling to identify their mistakes. These are shared at the start of a lesson and are so easy to make on word. In effect, these are just a process success criteria, but recasting them as an error-spotting checklist means pupils properly use it. Otherwise they might just tick each step willy-nilly.

Here are some example prompt sheets:

You can even use these for teaching at the start of the lesson. The lesson might, for example, feature the teacher deliberately getting a calculation wrong, before using the checklist to find their mistake. If there’s a TA in the room who can ham up playing the helpful partner, so much the better.

However you use them, it is key pupils internalise what they are doing (over the course of several lessons) so that they no longer need a written checklist. The aim is to get the checklist stored in their long-term memory. Giving pupils work to ‘mark’ from fictitious peers (with all the common mistakes) is a really good way of developing this.

Marking policy approaches for English/Literacy especially Writing

1. Use a redrafting approach to model primary school writing tasks

With writing, we use a redrafting approach. When the teacher looks at the books after a lesson, she makes notes on one piece of paper for the whole class about what went well and what still needs work.

This might include things to do with the technical accuracy of the writing; spelling errors, punctuation omissions, and other transcription mishaps, as well as any content improvements.

Where individual children have done particularly well or poorly, the teacher will make a note and use these in the lesson as a teaching point (where it is an error, she might use the mistake anonymously or write a similar sentence with the same error).

2. Showcase good practice in writing

In the next lesson the teacher will share extracts from pupils’ work, using either the visualiser or just a few typed lines to show examples of good work.

For example, she might showcase someone whose letter heights have the ascenders and descenders just right. She can then ask pupils to look at their work and rewrite one sentence from it, making sure they pay attention to letter heights.

Then she can move on to character description and show examples of work where this has been done well, pointing out what made the description so vivid.

3. Use a redrafting approach for mistakes in writing tasks

For mistakes, the teacher might share an example which an anonymous or fictional piece where the child has confused describing a character with listing their clothing, piling up adjective after adjective.

The children would then suggest how this might be improved. They might spend time with a partner – we always use mixed ability pairs for this – seeing if they included good description in their writing. Together the pupils reflect if the text would be improved by adding any additional description.

Finally, in pairs they read each other’s work together and suggest improvements, alterations and refinements which the author of the piece then adds – in green pen. We did, in fact, keep the green pen as it helps the teacher see what changes the pupils have made.

Spending every other writing lesson editing their work means they get through less than if the teacher had marked it for them. However, we think they learn more by forensically inspecting their own work and improving it, rather than simply writing more. It’s quality over quantity.

Plus, repetitive writing can lead to pupils simply recreating the same mistakes over and over again, no matter how many times the teacher’s marking tells them about full stops and capital letters.

The whole point of this approach is that the next step is the next lesson. You don’t need to write down the next step for each pupil either; you can either give them the opportunity to put it into action or teach them whatever the next step is for them.

Does this primary school no marking policy work for Ofsted?

Overall, the marking approaches have worked really well. Teachers still have to spend time after school looking at books, but much less time. Pupils have to think harder and put effort into improving their work. Of course, it is nerve wracking doing work surveys and seeing pages with very little annotation when you are used to a riot of colour!

Recently, I invited an advisor to come and do a work scrutiny with myself and the English leader. I was a bit nervous. Would he think I’d lost the plot? Though Ofsted’s new framework makes it clear that they will not comment on marking or make any judgments about it, it is scary throwing away the security blanket marking purports to offer.

But the pages showed children making good progress. It was certainly no worse than our old approach and in many cases much better. Also, despite almost half of lessons being given over to editing, books were still full of work.

Because our previous marking policy was such a huge workload drain, I think sometimes teachers – maybe subconsciously – avoided giving too many longer writing pieces. But now moving pupils on is just part and parcel of everyday teaching. That heart sinking feeling faced with 30 books just isn’t there anymore.

No more marking means better feedback

The other thing that really struck me was the increased quality of feedback on work. We were no longer checking for teacher compliance with our marking policy, so we could devote more energy examining the quality of book work.

It sounds silly to say now, but previously it was all too easy to assume that lots of dialogical marking inevitably meant that great teaching was happening. Of course, this isn’t necessarily the case at all.

Our previous marking policy was so overly tied to learning objectives and genre success criteria. A pupil could turn out work all year with the same basic words misconceptions or spelling mistakes never being fully addressed. Our old marking policy didn’t leave the time to address these essential issues once and for all.

Minimal marking policy at KS1

That is not to say we’ve got everything sorted. The younger the children are, the more difficult it is for them to edit their own work and the greater the degree of scaffolding the teacher needs to do.

Group editing

To combat this, in Key Stage 1 (especially with pupils who find writing hard anyway), the teacher often sets them a group editing challenge to do with her after the initial input. As such she can leave the rest of the class to get on with their paired editing.

Differentiating between proofreading and editing

Other pupils who might not get the most out our writing approach are those to whom writing so far has come more easily. They are great at helping their partner spot errors and improve content, but fail to adopt the same rigour with their own work.

In the worst cases, we might see two omitted full stops inserted and that’s pretty much it. The perception perhaps being that their work is pretty much perfect bar minor ‘slips of the pen’. This is very much a fixed mindset rather than the growth mindset we are trying to develop in school.

With this in mind, we’ve decided to make the difference between proofreading (error spotting) and editing proper (improving content) more obvious. With the expectation that everybody, including those who think their work is beyond improvement, work hard on redrafting their content just like adult writers.

The road ahead for marking in my primary school

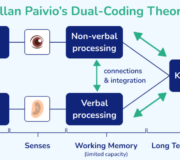

This brings me back to the MITA materials teaching triangle discussed in my previous post on banning marking in my school (pictured below).

Previously, our old approach over-scaffolded and spoon fed pupils. Leaving them with little thinking of their own to do. Perhaps, for some the new approach may go too far the other way. Only time will tell.

Some pupils still need extra support

Yet, returning to the triangle reminds us that some pupils will need a gentle prompt to narrow down their focus when hunting for mistakes. So if it isn’t enough for some pupils, we can provide scaffolding through a quick comment alerting them of errors. Or even a simple pointer; ‘description’, ‘ambiguous pronouns’ or ‘figurative language’.

Others might need even more support. For example, the teacher might need to draw a yellow box around a section of text to narrow down the search area for the pupil, alongside the comment that there are speech marks missing or tenses jumped or the same sentence structure over-used.

Where mistakes are deeply entrenched, the teacher may need to do some direct work modelling how to overcome these. For example, to clear up the confusion with apostrophe use.

However, with all of this, it is in addition to (and not instead of) the teacher modelling editing for pupils before the independent section of the lesson.

Is this really a ‘no marking’ policy?

You may say that this is beginning to look a lot like marking. Well, of course, it is a bit. But it is strategic minimal marking, using the very least marking possible for each child, on a case by case basis. What the teacher is not doing is using a marking code that does all the error identification for the pupil.

Just as in the triangle below, for almost all children the teacher input at the beginning of the lesson will be enough. Others will need a bit of a gentle prompt – a nudge in the right direction. A few might need some actual clues and one or two might need a lot more help.

The key element to any new no marking policy is to start with the assumption that all children can work independently given prior input.

Then increase the amount of intervention only if the pupil really can’t get on without it. Give children take up time; let them struggle for a bit, but above all, make sure they are the ones doing the hard work – not you.

Read more

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Skye – our AI maths tutor built by teachers – gives students personalised one-to-one lessons that address learning gaps and build confidence.

Since 2013 we’ve taught over 2 million hours of maths lessons to more than 170,000 students to help them become fluent, able mathematicians.

Explore our AI maths tutoring or find out about maths tuition for your school.