Goal Free Problems And Focused Thinking: How I Wish I’d Taught Primary Maths (3)

Clare Sealy looks at the benefits that focused thinking and goal free problems (also known as open ended maths investigations), can have when used in a KS2 classroom.

This article is part of a series published to help primary school teachers and leaders implement some of the insights and teaching techniques derived from Craig Barton’s bestselling book How I Wish I’d Taught Maths. Links to the other 5 articles appear at the end.

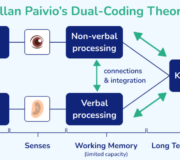

In the introduction to this series, I outlined how Craig Barton in his book How I Wish I’d Taught Maths described how he had changed his teaching. This was as the result of reading research around cognitive load theory in the classroom, and in particular, realising how easy it was to inadvertently prevent learning by overwhelming working memory through cognitive overload.

In order to avoid this, Craig now plans his teaching with cognitive science considerations at the forefront of his thinking. By making relatively straightforward changes to the presentation of information and instructional design, unhelpful cognitive load (called ‘extraneous’ cognitive load in the research literature) is removed.

Craig’s preferred technique for this is through direct instruction and worked examples, and as a result of these teaching strategies, working memory is freed up to think about what needs to be thought about.

Crib Sheet for How I Wish I'd Taught Primary Maths

Download the key findings from research; share with your staff, your SLT, and at your next job interview!

Download Free Now!Results from the research: Cognitive overload can affect pupils’ working memory

Cognitive overload is the enemy of learning. This is because if the capacity of working memory is exceeded, the stuff you actually want children to remember may not make it from the working memory to the long-term memory.

Since learning involves change in the long-term memory, if nothing has changed in the long-term memory, nothing has been learned. Sweller et al, 1998 suggest that teachers should take care to design instruction so that working memories are not overwhelmed. Fortunately, there is a simple way you can do this…

What are goal free problems?

While goal specific questions have an exact answer, goal free questions do not. They are a form of open ended maths investigation and an questioning in the classroom technique, and they are a great way to help prevent cognitive overload among pupils.

Goal free questions are the longer two or three-part reasoning questions that appear in maths, not simple calculations, and they are best used once you have taught the children something and now want them to apply it in a problem-solving context.

They are not intended to be used at the very start of teaching something.

These are ‘application’ questions, once the initial stage of how to do something has been taught and reinforced through deliberate practice in the short term, and retrieval practice across the school year.

If these open ended maths investigations are introduced before a topic has been fully grasped by pupils, this can result in confusion.

Meet Skye, the voice-based AI tutor making maths success possible for every student.

Built by teachers and maths experts, Skye uses the same pedagogy, curriculum and lesson structure as our traditional tutoring.

But, with more flexibility and a lower cost, schools can scale online maths tutoring to support every student who needs it.

Watch Skye in actionThe difference between a goal specific and goal free question

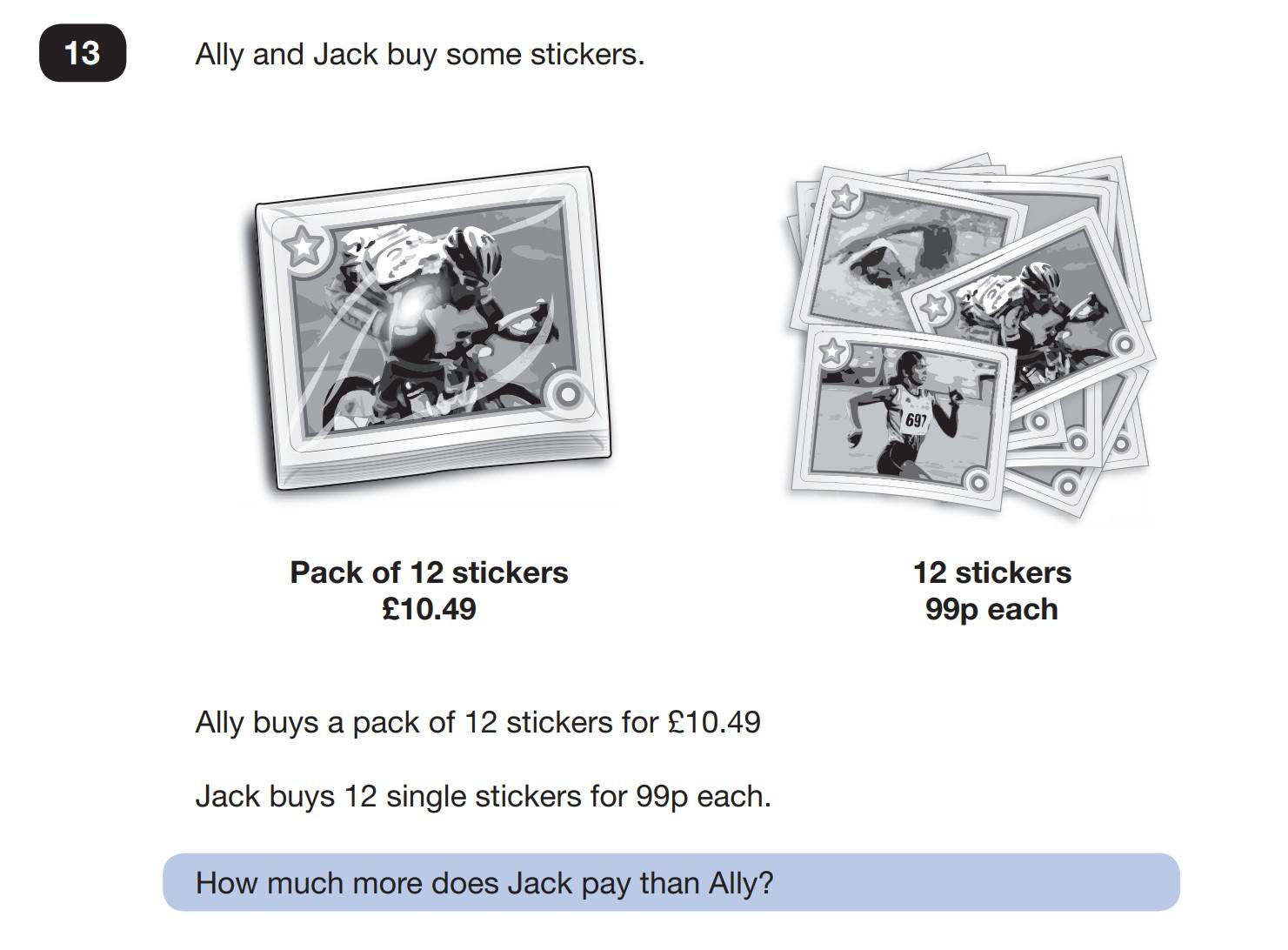

The following examples are all from the KS2 2017 Maths SATs Paper 2:

This is a goal specific question with a specific answer.

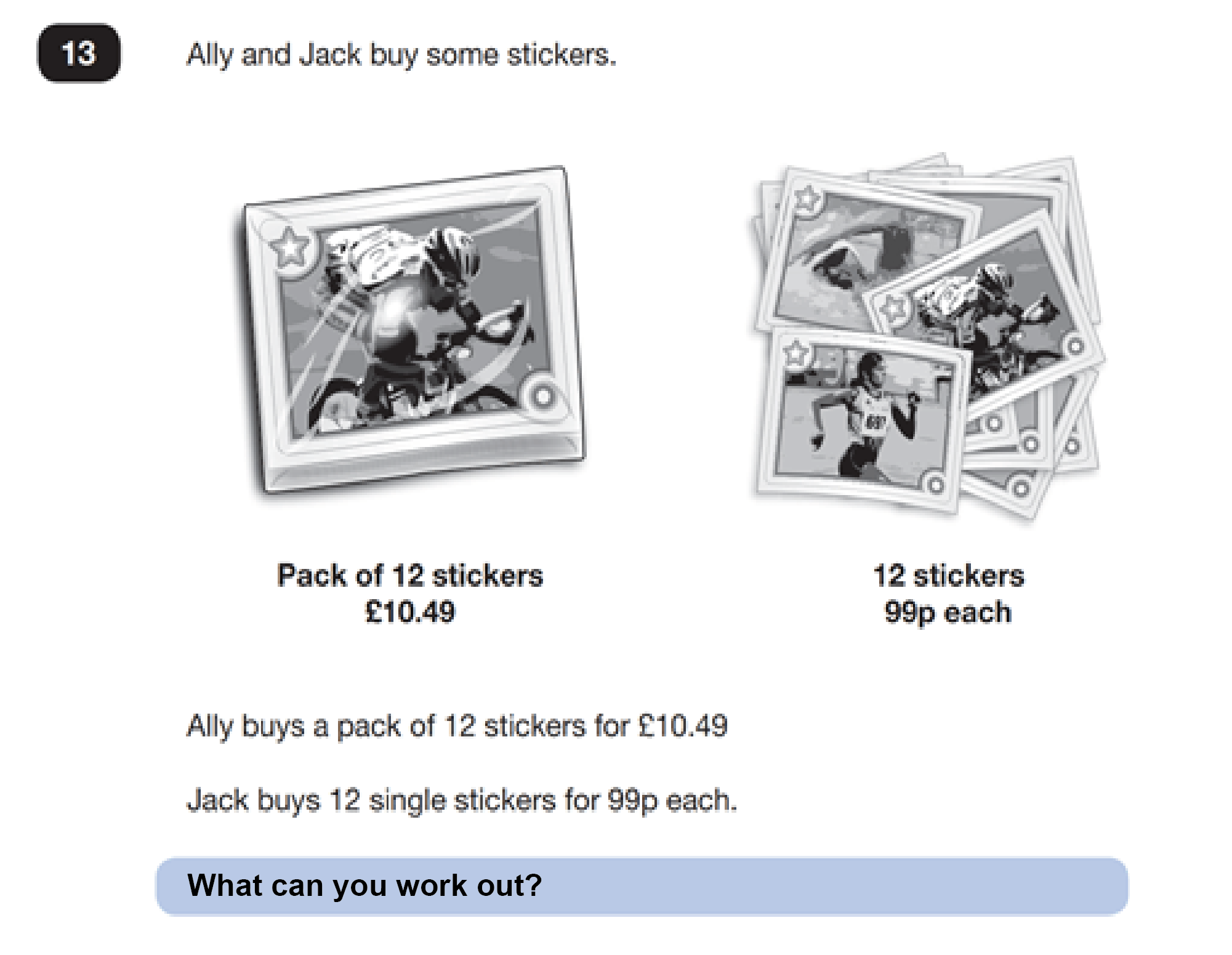

A goal free question would look like this:

So why are goal free questions better?

The reason why the second kind of question is better than the first is that in the second, the pupil can use metacognitive skills to work on parts of the question one at a time, rather than being overwhelmed trying to solve every part at once.

You can find out more about the sorts of thinking skills pupils might use from our blog on metacognition in the classroom.

Thanks to the open ended nature of these maths problems, pupils can focus on one singular part of the problem that they feel is important, and confidently solve this before moving on.

For example:

They would probably decide to work out how much 12 individual stickers cost. They would also not have any niggling, intrusive thoughts about what they need to do next competing for attention in their working memory. Therefore, all of their attention would be devoted to calculating 12x99p.

Having done that, they would probably then realise that buying individual stickers was a rip off! They might also work out other things, for example:

• If Jack had £11, how many individual stickers could he buy?

• Or what is the cheapest amount you could pay to get 16 stickers?

But whatever they decided to work out, they were thinking about that and that alone.

Why the traditional method of asking questions can hinder pupils’ learning

With a conventional problem, concerns about the final goal can intrude upon their thinking. The pupil’s attention is split between thinking about the first step and thinking about the other steps that they need to take next.

Therefore, even if they successfully answer the question, they may not have learnt anything generally that could be transferred to new kinds of problems.

Their attention has not been focused enough.

Goal free questions are a great way to help pupils solve the problem in front of them

Once you have given the children the goal free version of the question and various things have been worked out, at that point you can, if you wish, share the goal specific question. You should then realise the hard work of answering the question has already been done and a final tweak might be all that is now needed.

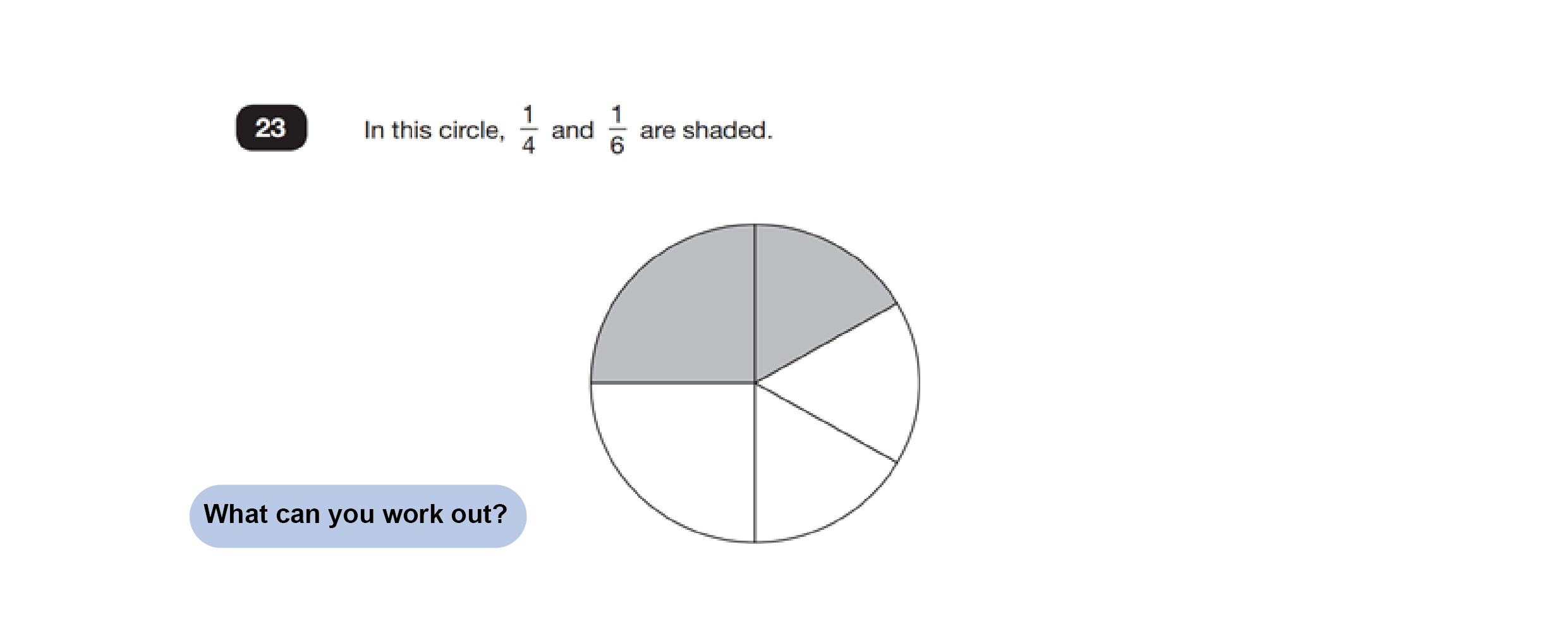

Consider this example, adapted to be open ended and goal free:

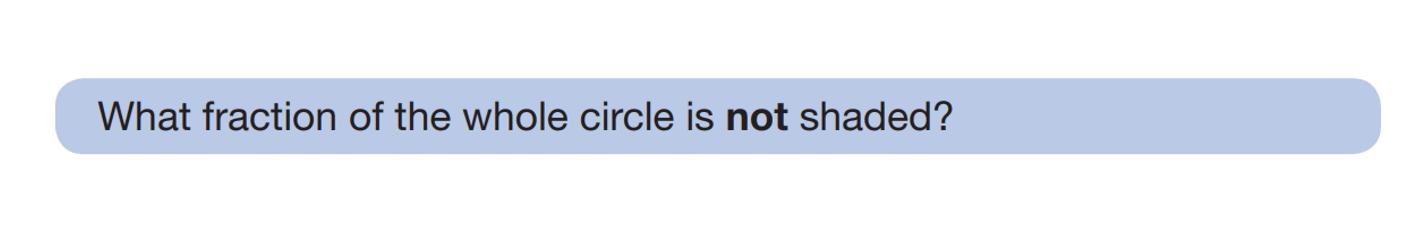

Without a goal specific question looming over them, children will probably quickly be able to identify the size of the individual unshaded parts. Then they might decide to work out what fraction is shaded. Then when the goal specific question is revealed…

…answering it is very easy. Even if they only initially worked out the size of the individual unshaded parts, they are still ahead of the game having done so.

Best practice for open ended, goal free questions

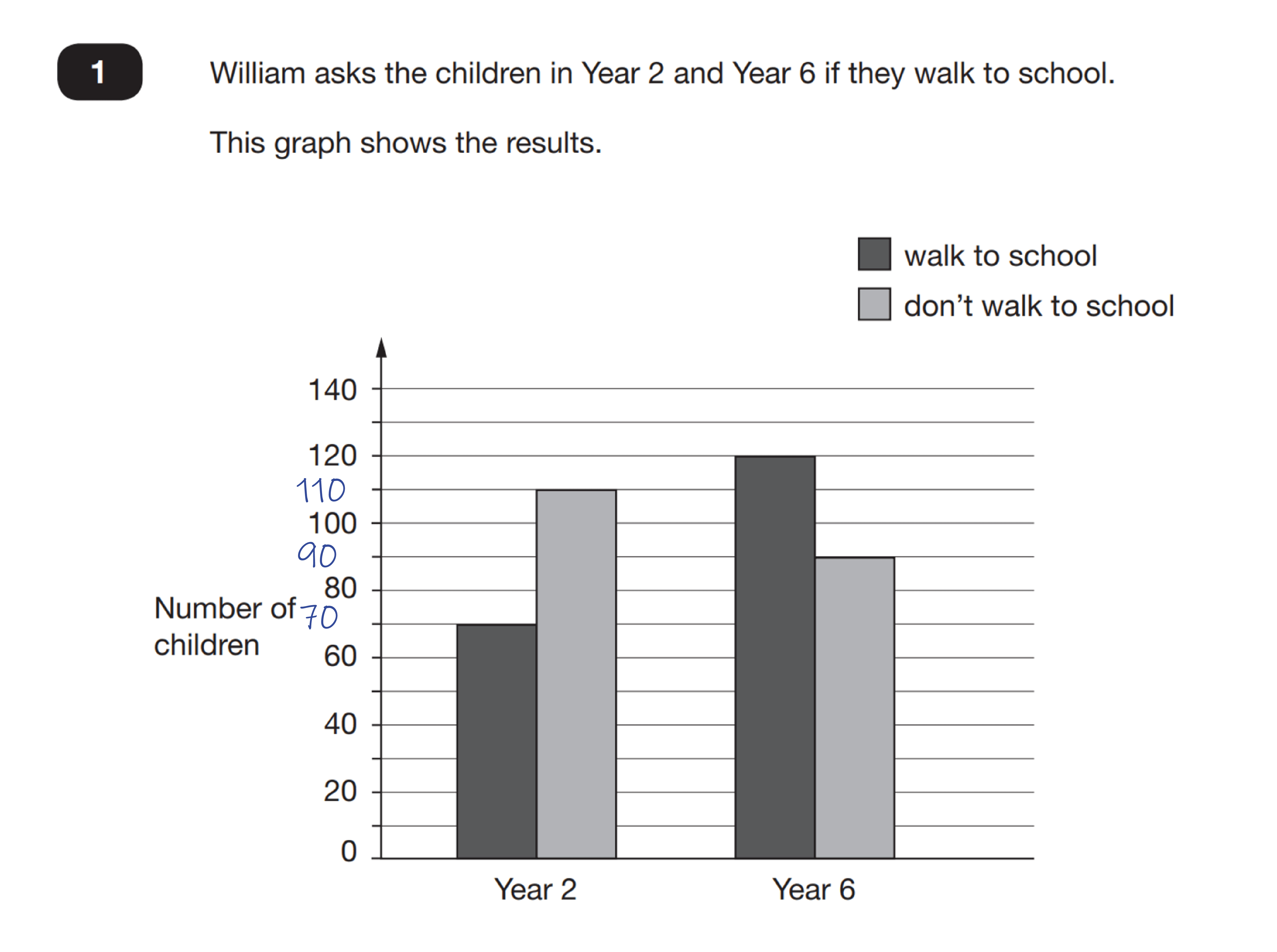

Using goal free questions works particularly well with graphs and geometry questions, with the pupil asking themselves: “What can I work out first?” before worrying (or being told) about what the question actually says.

Doing it this way in a test situation, the pupil is more likely to answer the actual question than if they had tried to solve it from the off. This is because they know that their initial goal free musing is a prelude to the final step of telling the examiner the actual thing that will get them marks.

So, for example, teach pupils to hide the question and first of all annotate the graph to show what it tells them.

As well as annotating the axes, the child also annotates their paper with the following.

Difference yr 2 – 110-70=40

Difference yr 5 – 120-90=30

Walk – 70+120=190

Don’t walk – 110+90=200

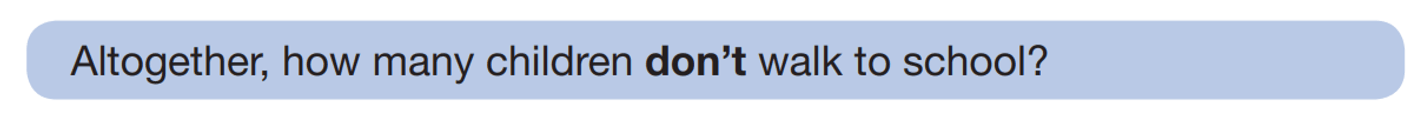

Then when the final specific question is revealed…

…The solution is already worked out. However, by not having to worry about the final question during the initial annotation stage, their attention is much better focused as they explore the graph to find answers to their own question.

It is not necessary to always share the ‘final’ question, especially during the early knowledge-acquisition phase. Goal free, open ended questions are particularly useful the first time you want pupils to apply a skill you have just taught. Goal free questions with an eventual goal specific big reveal are useful when revising in readiness for a test.

3 tips for bringing focused thinking and goal free learning into your classroom

1. Prepare a dedicated selection of open-ended maths investigations for your class in the form of problems, activities or worksheets

2. Present existing questions to students in the manner seen above, asking them what they can take from the question before the final request is revealed

3. Use goal free questions as a way to further cement knowledge, using them after you have taught pupils a principle. This will encourage focused thinking within the classroom

I hope that the theories about goal free, open ended maths investigations and focused thinking presented in this blog prove useful in your classroom.

Sources of inspiration

Sweller, J., Merriënboer, J.J.G. and Pass, F.G.W.C. (1998) ‘Cognitive architecture and instructional design’, Educational Psychology Review 10 (3) pp.251-296

This is the third blog in a series of 6 adapting the book How I Wish I’d Taught Maths for a primary audience. If you wish to read the remaining blogs in the series, check them out below:

Read more:

- 20 maths strategies that we use in our teaching to guarantee success for any pupil.

- Quality First Teaching Checklist: The 10 Most Effective Strategies For Primary Schools

- Differentiation In The Classroom: The 8 Strategies That Will Support Every Pupil To Reach A Good Standard

- Learning and Memory In The Classroom: What Teachers Should Know About Summer Learning Loss – And How To Fix It

- Teaching ‘Lower Ability’ Students Maths: “Are We Bottom Set?”

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Skye – our AI maths tutor built by teachers – gives students personalised one-to-one lessons that address learning gaps and build confidence.

Since 2013 we’ve taught over 2 million hours of maths lessons to more than 170,000 students to help them become fluent, able mathematicians.

Explore our AI maths tutoring or find out about one to one tuition for your school.