Formal Lesson Observation Just Isn’t Worth It: Here Are The Alternatives That Work Better

Formal lesson observation always used to be the unavoidable side effect of teaching in a UK primary school. Here Headteacher Clare Sealy explains why she ditched the idea of lesson observations in her primary school, and what different lesson observation and feedback mechanisms she came up with instead.

What is lesson observation

Lesson observation is, typically a termly event where, teachers in the UK are observed teaching a single individual lesson by one or more of their managers or SLT with the aim of assessing the quality of teaching that’s taking place.

In many schools, this lesson observation will still be graded, despite Ofsted doing away with grading lessons and fairly conclusive evidence that grading is inherently unreliable.

Ofsted Preparation Guides

Prepare for your next inspection with this step-by-step maths framework. Includes checklists and questions that Ofsted have asked during visits to other schools.

Download Free Now!Why is lesson observation important

The only valid reason for most of what we do as primary school teachers, has to be ‘does it improve pupil outcomes’, whether that’s subject knowledge, progress, confidence or any other measure you want to put on it.

The jury is still very definitely out on whether formal lesson observations – graded or not – lead to improved pupil outcomes, through improved teaching or faster pupil progress.

At this point, are they simply an expected ritual that leaders conduct because they think they have to? And by going through the motions in this way, might they make teaching less effective?

We stopped using any kind of proforma or Ofsted criteria for lesson grading a couple of years ago and, last September, we decided to stop doing termly lesson observations at all.

Why we dropped lesson observations at school

We stopped doing formal lesson observations because we didn’t find them helpful for improving practice or ‘taking the temperature’ of provision quality at our primary school. The largest problem, we found, was that lesson observations were too long and too infrequent.

Teachers also found them hugely stressful. They over-prepared, laminating everything in sight. What you ended up seeing was not their everyday practice but a pumped-up super lesson, designed to impress the observer rather than learning.

Of course sometimes these lessons went wrong – as lessons do – and the teacher would be devastated. Then we’d have to put them through that stress again a week later so they could “prove” that they really could teach. When we knew this anyway!

Plus a teacher who might be having problems could always pull off a tour de force and do a decent lesson on the day. Then a whole term would pass before they were observed again. That’s a lot of learning time where pupils might not be receiving the education they deserve.

The whole system seemed designed to cover up problems and impress leaders, while simultaneously being incredibly stressful for teachers.

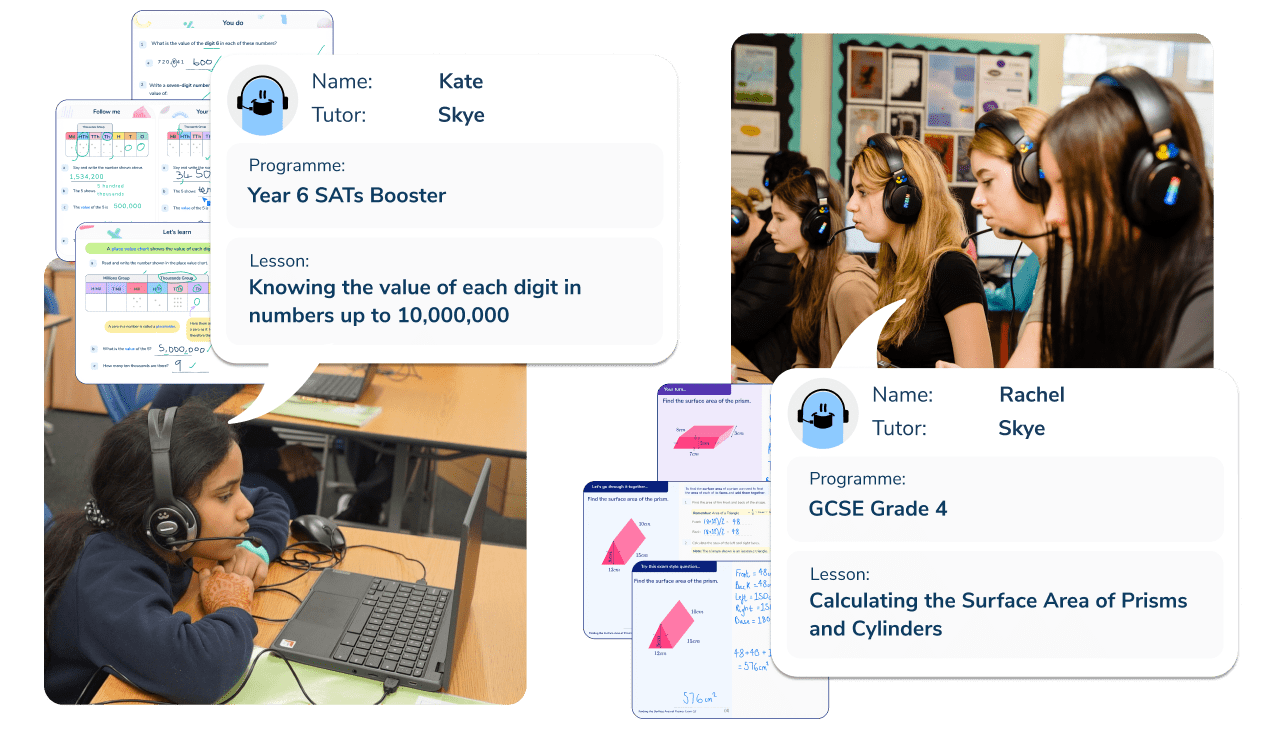

Meet Skye, the voice-based AI tutor making maths success possible for every student.

Built by teachers and maths experts, Skye uses the same pedagogy, curriculum and lesson structure as our traditional tutoring.

But, with more flexibility and a lower cost, schools can scale online maths tutoring to support every student who needs it.

Watch Skye in actionPrimary school learning is messy, not performance oriented

We feel the once-a-term formal lesson observation risks luring teachers down the path of aiming for performance. It makes leaders rely on a once-a-term impression to quality assure provision. Good performance may look neat and tidy (the teacher speaks and the children magically get it) but good learning is messy and takes time.

Read more

Informal classroom observation

I recently saw a Maths lesson in reception on addition. During my classroom observation children were learning to do missing number additions (2 + ? = 5). Those furthest ahead were using a number line to do this. It was challenging and not all children could do it independently by the end of the lesson.

They didn’t ‘perform’, they struggled; but I was delighted to see children thinking hard and trying to get it. I was especially happy to see the teacher patiently modelling it over and over.

I knew that this was only the first in a whole series of lessons. The children would undoubtedly go over this multiple times with that teacher and throughout their primary careers. There was no rush to get it right first time and I felt privileged to be there at the very beginning of this journey. Our post-observation feedback session was just a chat to get her views on how the lesson went and to check if we had both assessed it similarly.

In a couple weeks or so, I’ll drop by her Maths lesson again for 10 minutes. By then I’m sure it will be more secure.

My alternatives to formal lesson observations

That is what I do now at my school instead of a formal lesson observation observation process. I regularly drop into the primary classrooms, look at books and talk to the children. That’s all. It provides much better information on how things are really doing, without the distorting effects of high stakes make-or-break observations.

In fact, last September our entire school moved to a system of very frequent, low stakes observations just like this. The approach itself is based on the system described in Leverage Leadership by Paul Bambrick–Santoyo.

Lesson observation examples

The new 10 minute drop-in lesson observations give us plenty of examples of the teaching practice that’s taking place.

Not only can we see if generic teaching skills are present: is behaviour for learning good, is the teacher using their voice effectively, is questioning open and appropriate, and are expectations of the children are high enough.

One helpful use of a lesson observation that can be done quickly and without stress for any qualified teacher, is that it helps us see if new initiatives are being put in place. For example, this September we delivered INSET on developing vocabulary, sharing strategies from Isabel Beck’s Bringing Words to Life.

Having sat in on over 100 lessons in these more informal classroom observations since September, I can say with complete confidence that these strategies are now routinely embedded in by both our teachers and our trainee teachers. And I’m able to see a variety of approaches.

With formal lesson observations, I might have seen teachers use it in their ‘show’ lesson, but wouldn’t know if it was a routine part of their practice.

Lesson observation feedback

Of course the drop-in approach does not give teachers detailed lesson observation feedback or guidance to analyse whether a strategy is working or not. It is not designed to. Instead, it is an ‘early warning system’, picking up where things are not quite as they should be.

For instance, I saw a Maths lesson where the teacher (an NQT) was teaching equivalent fractions. They had previously used a fraction wall and she assumed this meant the concrete and pictorial elements of learning were ‘done’. As such, she was now teaching it purely through the written algorithm.

While it looked like the children were ‘performing’ this correctly, I was concerned she had skipped conceptual understanding and maths misconceptions in fractions might be occurring. I was also concerned that, if the teacher was rushing to solely abstract algorithms when teaching fractions, this might be happening across the Maths curriculum.

By catching this early on in one of my 10 minute drop in lesson observation sessions I was able to flag it with the subject leader as an issue to work on.

The lesson observation feedback then comes as part of a co-teaching / peer support lesson with the subject leader. To ensure teachers still receive a proper analysis of their teaching, subject leaders observe, coach and co-teach with their peers. These sessions are purely developmental; they exist only to help teachers teach more effectively and are not written up.

The leader often spends the whole lesson analysing a lesson, then discusses it with the teacher later that day. From there, the two agree on a course of action.

How we deal with a teaching ‘red flag’ after a drop-in lesson observation

If a drop-in flags up an issue (as in the example above) the leader works with the teacher to help them to improve. With the NQT, we knew they needed to understand the rationale behind CPA better and utilise bar modelling more effectively.

After attending a course on the CPA approach and bar model techniques, the class teacher and Maths lead agreed that the leader would plan and teach that part of the lesson next time. The following week, the lead would return and see if class teacher could deliver it independently (with planning support).

After this, the leader returned a week later to see a lesson with no planning support given in order to check if the teacher was applying what she had learnt. She was. At her next drop-in classroom observation, the teacher asked me to come and see a maths lesson again, because she was so proud of and excited by her new teaching tool.

What about lesson observation evidence for Ofsted?

This type of support is purely developmental. It does not contribute to performance management at all. Subject leaders do not need to write up their lesson observations or write accounts of the support they have given beyond logging that it was.

In fact, the only exception is if a teacher is really struggling and needs a support plan. Then, of course, we have to keep fuller records. Overall, notes from the drop-in teacher observations are brief bullet points and subject leaders essentially write nothing.

As such, I am sometimes asked how we will prove to Ofsted that we have been monitoring and supporting colleagues without detailed ‘evidence’. Were Ofsted to ask for evidence I would tell them that they can get all the evidence they need by talking to staff. From those who have provided support to those who have received it. And under the new Ofsted inspection framework it seems that this sort of evidence gathering is very unlikely ever to prove of interest to the inspector.

Say No to the verbal feedback given stamper

I also eschew staff using the notorious ‘verbal feedback given’ stamper. I feel strongly that staff should not waste precious time recording something just to prove it happened to an external audience. If our approach has had a successful impact, the books will show good progress, lessons will be effective and the data will reflect that.

As we don’t grade drop-ins, I can’t produce a table for my headteacher reports to governors detailing the percentages of lessons seen at each of the four Ofsted grades. Instead I report on my overall impression of teaching: having dropped into hundreds of lessons, looked at books, talked to children and staff, and analysed data.

To me, tables and charts give the illusion of rigour and certainty, but in the end, the information they present is no more objective than a narrative approach. Indeed, the numbers manipulated within an Excel spreadsheet can be a mirage to the real narrative behind the scenes.

Reactions from staff to these lesson observations

In December I asked teachers for their thoughts on the new system. It was unanimously preferred to the previous formal lesson observations. They found it to be less stressful and more helpful. With both SLT and teachers on the ground preferring this approach to observing lessons, it’s a win-win situation.

I can’t imagine going back to our old lesson observation model; it seems so pointlessly stress-inducing, yet yields so little usable information. In short, our old approach didn’t help us make things better, either for pupils or as part of our whole school improvement. Our new approach does.

By helping teachers up their game a little bit every week, over the course of a year we’ve made more improvement than would ever be possible from two or three termly observations. It’s the same marginal gains approach that led the British Cycling Team to Olympic victory!

We wanted a better way and, by implementing a system that helps us reflect together and be honest about problems, we believe we’ve found one. No blame, just the aim of making learning more effective.

Often issues picked up during these light touch lesson observations can be remedied swiftly by some targeted CPD. Find out some of the options for affordable and free professional development here or visit the Third Space Maths Hub of CPD videos.

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Skye – our AI maths tutor built by teachers – gives students personalised one-to-one lessons that address learning gaps and build confidence.

Since 2013 we’ve taught over 2 million hours of maths lessons to more than 170,000 students to help them become fluent, able mathematicians.

Explore our AI maths tutoring or find out about one to one tuition for your school.