AI Literacy in Schools: A Practical Guide for Teachers and Leaders

For centuries, schools have focused on helping young people to read, write, and work with numbers. Today, another core skill is becoming just as important: AI literacy. The ability to understand and work with digital tools, specifically artificial intelligence, is shaping how students learn, how teachers teach, and the skills that will be needed in future jobs.

AI is already part of daily life in education, from the tools students use to research and create, to the systems that organise lessons and manage assessment. Yet many encounters with artificial intelligence happen informally and without guidance. Schools that take a deliberate approach can help staff and students to use these tools with clarity and confidence.

This guide sets out what AI literacy means in practice, why it matters for both primary and secondary education, and how schools can start and continue the work. It offers a balanced view of opportunities and risks, and provides practical steps for teachers, school leaders and policy makers who want to integrate AI literacy into their curriculum, culture and digital strategy.

Discover how AI tutor, Skye, can improve your students’ confidence and maths results.

Get in touch to arrange a free AI maths tutoring session.

Try a free sessionReading, Writing, Arithmetic… and Algorithms: What is AI literacy, and why does it matter?

AI literacy is the ability to understand, use and interact with artificial intelligence responsibly and safely. For teachers and students, it means knowing what AI is, where it appears in daily life and how to work with it thoughtfully, much like any other learning or digital tool.

An effective AI literacy framework in educational settings brings together four key elements:

- Understanding: Knowing what AI systems can and cannot do, how their outputs are produced and where they appear in everyday tasks.

- Ethics: Recognising that every AI system reflects human choices and values, and exploring fairness, privacy and the consequences of design decisions.

- Safe use: Making informed decisions about which AI tools are appropriate, protecting personal data and recognising risks such as bias or misinformation.

- Judgement: Asking questions of AI outputs, checking information and avoiding uncritical acceptance.

These skills are now essential for both primary and secondary education. Generative AI tools, language translation services and Artificial intelligence-enabled classroom platforms are already part of learning and daily life. Without structured teaching, students’ first experiences often happen without guidance or awareness.

AI literacy in schools

AI now appears in many parts of school life, though often in quiet, unplanned ways. A student might test a homework helper to check a concept, experiment with an image generator for an art project, or use a translation tool to understand a text. These moments can be useful, but they can also raise questions about accuracy, bias and safety. Without shared understanding, experiences of AI can be inconsistent. AI needs human expertise.

How schools are using AI is developing. Some teachers have begun to explore AI tools for planning, feedback or generating lesson ideas, discovering where they can support creativity or free time for other priorities. Many schools have even started to expore AI tutoring. Others are more cautious of AI adoption, watching developments while considering the right moment to start. Both positions are reasonable in a period of rapid change.

Curriculum references to AI vary. Computing lessons may introduce algorithms and data, and PSHE might cover online safety, but opportunities to practise critical use of AI are still rare. Embedding these skills in existing subjects could make them part of everyday learning rather than a separate activity.

Policy work is ongoing. Many safeguarding and IT guidelines were created before current AI tools became widely available, so leaders are reviewing how these apply to today’s tools and contexts. Each adjustment is a chance to connect policy with practice and make expectations clear.

Understanding these varied starting points helps schools decide how to move forward. AI literacy frameworks can grow steadily, shaped by the school’s own values, priorities and pace.

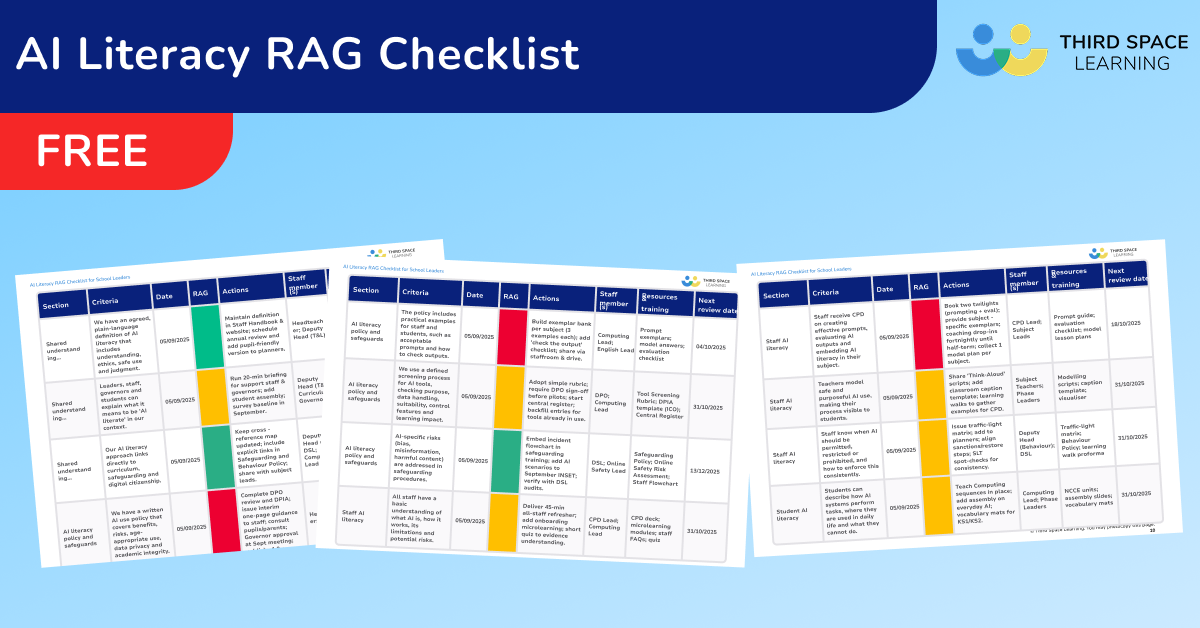

AI Literacy RAG Checklist

Download this practical AI audit, aligned with the DfE’s guidance on AI use in schools, to assess your school's AI literacy readiness. Includes a completed example and blank AI literacy RAG checklist for primary and secondary school leaders

Download Free Now!The role of AI literacy

AI literacy sits at the intersection of technical knowledge, critical thinking and digital citizenship. A strong literacy framework defines the skills, attitudes and safeguards that protect students and prepare them for a future where AI is part of both learning and life.

For teachers, AI literacy strengthens professional confidence, helping them use AI tools where they add value and to anticipate potential risks to wellbeing or academic integrity.

For school leaders, it supports informed decisions about resources, policy and communication with parents.

5 core components of AI literacy in education

AI literacy in schools is not just knowing that a tool exists or how to operate it. It is the gradual development of skills, attitudes and safeguards that help students use AI in the classroom in ways that are safe, thoughtful and purposeful.

1. Understand how AI works

Students benefit from a basic grasp of what AI systems do, how they process data and where their limitations lie. This is less about coding expertise and more about recognising that AI cannot think like a human or do what teachers do, that it works only with the data it has, and that its outputs can be incomplete or incorrect. This understanding helps learners question results rather than accept them uncritically.

2. Recognise ethical and social impacts

Every AI system is shaped by human choices. From the data it uses to the rules that guide its outputs, these decisions influence fairness, privacy and the distribution of benefits. Exploring these questions makes abstract concepts like bias more tangible and relevant.

3. Develop safe and critical use

AI literacy includes knowing how to protect personal data, avoid unsafe applications and check the reliability of AI-generated content. Students can learn to recognise signs of bias or misinformation and know when to involve a trusted adult if something feels wrong.

4. Apply AI purposefully

Used well, AI tools in education can support tasks such as generating ideas, refining drafts, testing hypotheses or exploring different perspectives. The emphasis is on enhancing thinking, not replacing it, so students remain active participants in the learning process.

5. Embed wellbeing, safeguarding and citizenship

AI literacy connects closely to digital citizenship. It includes making informed choices about technology use, participating respectfully online and maintaining a healthy balance between on-screen and offline life.

When introduced gradually, revisited often and linked to real learning scenarios, these components can help students and staff develop the knowledge and judgement needed to engage with AI confidently in both education and everyday life.

5 practical starting points for schools

Integrating AI literacy into teaching and learning does not require a fully formed programme from day one. A series of small, deliberate steps can build confidence for staff and students, while giving leaders the insight to develop AI literacy initiatives to suit their context.

1. Audit what is already happening

Find out which AI tools staff and pupils already use. This can reveal where effective practice is taking place, as well as highlighting tools that may not meet safeguarding or curriculum needs.

An audit can also uncover background uses of AI, such as translation or automated feedback, that influence learning without always being visible.

2. Link to recognised frameworks

Draw on existing guidance from trusted sources. The OECD and UNESCO offer AI literacy frameworks that set out the knowledge and skills learners need. The European Commission’s DigComp 2.2 framework adds competencies for using digital technologies critically and responsibly, including AI-specific elements. Referencing these helps ensure your approach aligns with leading international experts and can make it easier to explain priorities to staff, governors and parents.

3. Provide space for CPD

Education leaders and teachers need time and support to develop their understanding of AI and explore AI-enabled tools in a safe, low-pressure setting. This could take the form of short CPD sessions, peer workshops or subject-based discussions.

Encouraging staff to share examples of effective learning scenarios can help improve basic knowledge, confidence and spark new ideas.

Recommended CPD: Try the AI literacy course created specifically for school leaders.

4. Use safe, age-appropriate tools

Select AI tools with strong privacy protections and suitability for the age group.

- In primary education, that might mean using guided environments with clear prompts and structured discussion.

- In secondary education, a wider range of tools may be possible, but still with oversight to ensure they serve the learning purpose.

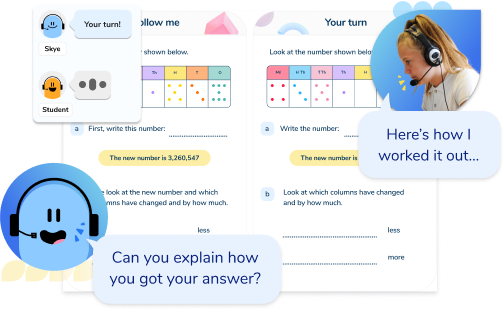

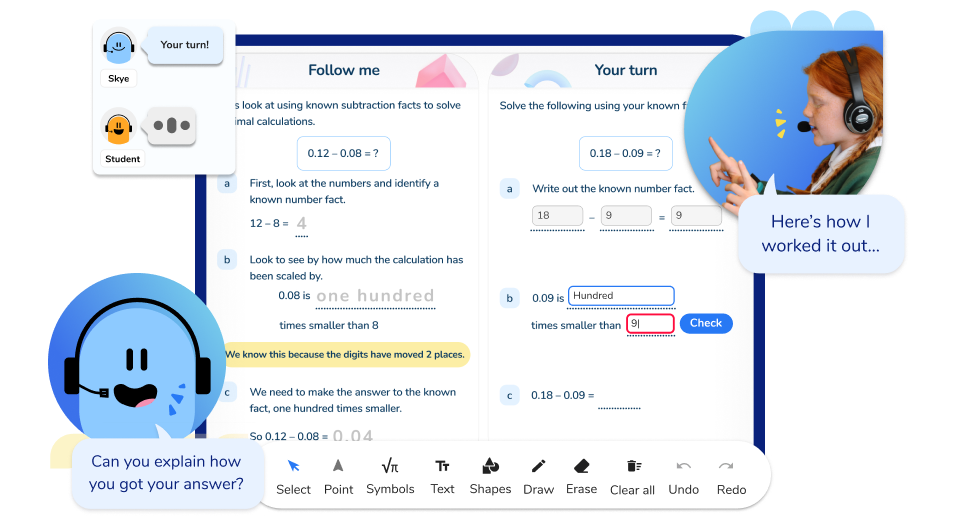

Skye, the age-appropriate AI maths tutoring tool

Hundreds of schools across the country are implementing AI tutoring with AI maths tutor, Skye. With unlimited sessions for unlimited pupils, primary and secondary schools can provide access for every KS2 and KS4 learner who needs additional support with maths.

Skye, the spoken AI tutor, uses age-appropriate, curriculum-aligned lessons designed by our team of maths experts and former teachers. It adapts to the pace of each individual to provide personalised maths help that closes learning gaps and accelerates maths progress.

A recent study by Educate Ventures Research found that pupils receiving tutoring from Skye improved their accuracy from 34% to 92% within a session.

Find out more about the best AI tutors and 5 use cases for how schools like yours are using AI tutoring.

5. Identify curriculum touchpoints

Integrating AI literacy into existing subjects keeps it relevant. In English, students could compare different writing styles produced by generative AI. In Computing, they could explore how algorithms perform tasks and where bias might appear. In PSHE, they could discuss the ethics, wellbeing and citizenship aspects of AI use.

Leading with purpose: policy, culture, and what ‘good’ looks like

Strong AI literacy begins with leadership that treats it as part of the school’s long-term vision for teaching, learning and safeguarding. It is not simply about keeping pace with technology, but about ensuring staff and students can work with AI safely, thoughtfully and in ways that reflect the school’s values.

Develop clear, adaptable policies

AI policies should give staff and students clarity on expectations while leaving space to continue developing AI literacy. Policies need to address the following with examples relevant to everyday classroom practice:

- ethical use

- data privacy

- academic integrity

AI in schools guidance from the DfE, Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSIE) and the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) can provide a baseline, while OECD, UNESCO and European Commission frameworks can help define the knowledge and skills expected of AI-literate students.

While there is no official AI guidance from Ofsted, much can be inferred from their most recent commentary.

Embed AI literacy across school life

When AI literacy is included in CPD, curriculum planning and pastoral work, it becomes part of the school’s culture. Education leaders can encourage each subject area to consider the potential benefits and risks of AI in their discipline, and to revisit AI literacy as part of ongoing professional development. This reinforces the idea that AI literacy grows over time, through regular attention and shared responsibility.

Define and share a vision of excellence

A shared understanding of what ‘good’ looks like can guide decisions and help measure progress. This might include:

- Ethical and safe practices embedded in everyday teaching

- Staff with the technical knowledge to use AI-enabled tools appropriately

- Students able to reflect critically on their AI use and contribute to policy through structured feedback

- A clear literacy framework understood by staff, students and parents

Connect leadership to safeguarding and innovation

AI literacy is part of protecting students as well as preparing them for the future. Safeguarding policies should cover AI systems in the same way they cover other digital technologies, while also encouraging safe, creative use in learning scenarios.

Make policy visible in practice

Policies have the most impact when they are reflected in day-to-day routines. Consistent language from staff, assemblies exploring AI’s role in society, and subject leaders sharing examples of effective prompts can all help build a culture where AI literacy is simply part of how the school operates. Before long, AI will start to feel like wifi, part of the normal way of operating.

Responding to 5 common concerns

Leaders and teachers are carrying real pressure. Time is tight. Expectations from parents and students are high. The world is moving very fast. Our aim here is reassurance with substance, so that you can make informed decisions and teach with confidence.

AI raises practical and ethical questions for schools. Addressing them directly helps staff feel confident and ensures students learn safe, purposeful use.

1. “Students know more than we do”

Many students encounter AI before teachers do, but familiarity is not the same as judgment. The “digital native” label is misleading and unhelpful. Teachers set the boundaries, choose the context and guide exploration.

Scenario-based discussions work well: students analyse AI outputs against agreed criteria such as accuracy, bias and relevance, then reflect on what worked and why. This allows peer learning while keeping professional authority at the centre.

2. “AI undermines creativity or rigour”

Well-designed tasks make AI a starting point, not the finished product. In English, students might compare two AI-generated openings for a persuasive speech, then adapt them for a target audience. In Geography, they could assess AI-suggested hypotheses for fieldwork.

Recording prompts, annotating drafts and explaining improvements ensures creativity and rigour remain with the learner.

3. “It is too soon, or too uncertain”

Delaying action leaves AI use to happen unseen. Start small with a short pilot in one or two subjects, set clear boundaries, measure impact and adapt. Protect data privacy, avoid under-13 accounts and safeguard assessment integrity. Begin with trusted guidance and add context-specific expectations.

4. “Using AI is affecting how students think”

Over-reliance on AI can weaken critical thinking. Short routines such as comparing AI-generated summaries with trusted sources, or reviewing AI-provided maths solutions step by step, help students evaluate rather than accept. Make clear when AI is off-limits for mastery tasks and when it is permitted for exploration, always with evidence of process.

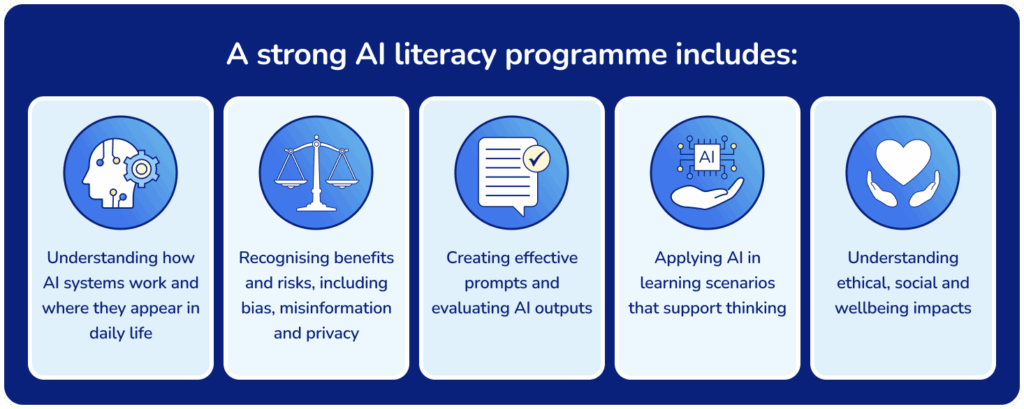

5. “We are not clear on what skills to teach”

A strong AI literacy programme includes:

- Understanding how AI systems work and where they appear in daily life

- Recognising benefits and risks, including bias, misinformation and privacy

- Creating effective prompts and evaluating AI outputs

- Applying AI in learning scenarios that support thinking

- Understanding ethical, social and wellbeing impacts

Staff need parallel knowledge plus the skills to select tools, embed AI literacy into the curriculum, recognise misuse and model safe, purposeful use.

6 practical steps for leaders that help right now

1. Set classroom norms for safe, purposeful use

Agree on when AI tools may be opened, how prompts are recorded and how outputs are checked. Require students to paste any prompt into their notes to build traceability and support coaching over time.

2. Teach effective prompts as part of literacy

Show students how to give purpose, constraints and sources. For example:

- Purpose: draft a balanced summary for a Year 8 audience.

- Constraints: 150 words, plain language, one benefit, one risk, two sources to check.

This keeps AI in service of the task and supports informed decisions.

3. Protect assessment while allowing practice

For coursework, require planning artefacts, annotated drafts and a short viva. For homework, alternate AI-permitted tasks with AI-free tasks, making expectations visible in the brief.

4. Use a simple, repeatable risk screening process

Before introducing an AI tool, check:

- Purpose: Is it aligned with curriculum or pastoral goals, and can it promote AI literacy?

- Data: What is collected, where stored and who can access it? Does it meet UK GDPR?

- Age suitability: Is it appropriate and safe for the age group?

- Control: Can functions be limited to prevent unsafe use?

- Impact on learning: Does it encourage critical thinking and creativity rather than over-reliance?

5. Offer quick, regular CPD

Fifteen-minute slots in existing meetings can build confidence quickly, especially when linked to real classroom practice. Share examples and normalise high expectations.

6. Bring parents with you

Provide a short guide explaining AI literacy, where it appears in the curriculum and homework rules. Include three conversation starters families can use at home to build shared understanding.

Handled in this way, AI tools become part of a wider culture of curiosity and care. Teachers retain control of the learning journey, students develop skills for safe, thoughtful use and leaders can grow AI literacy initiatives that feel realistic and grounded in school values.

What the experts say on AI literacy: insights from research and practice

AI is not neutral: Professor Wayne Holmes

Holmes’ work with UNESCO shows that every artificial intelligence system reflects the data, values and priorities of the people and organisations that created it. He warns that treating AI as an impartial helper hides how bias, power and commercial interest shape its outputs.

For schools, this means AI literacy must include explicit teaching on how to question a tool’s origins, purpose and likely limitations. Leaders should also ensure that policies address ethics and governance, not just functionality.

Co-design matters: Professor Judy Robertson

Robertson’s research on computing education and the “Data Education in Schools” programme demonstrates that involving students in designing and critiquing AI projects deepens their understanding far more than passive use.

Professor Judy Robertson advocates giving young people authentic problems to solve with AI tools, combined with structured teacher guidance. This builds transferable skills in critical thinking, collaboration and ethical reasoning, and ensures AI literacy is rooted in purposeful, age-appropriate tasks.

Speculative thinking is vital: Professor Jen Ross

Ross’ work on digital futures in education focuses on asking “what kind of future do we want with AI?” rather than only “how does AI work?”. Her methods use structured activities where students and staff imagine near-term and longer-term scenarios for AI in their subject, weighing potential benefits and potential risks.

A futures-oriented approach makes values and priorities visible, helping schools align AI literacy with their broader vision for education.

What schools can take from this

- Treat AI as value-laden, not neutral: Teach students to identify whose goals and values are embedded in AI systems, using case studies and tool comparisons. Apply the same scrutiny when selecting tools for school use.

- Integrate co-design into learning: Build AI literacy initiatives around real-world projects where students and staff work together to plan, test and evaluate AI use. Include explicit discussion of ethics, bias and reliability at each stage.

- Use futures thinking to keep purpose in view: Run regular, structured scenario-building exercises that encourage reflection on AI’s role in different subjects and contexts. Compare these visions to current practice and adapt policy accordingly.

- Connect practice to recognised frameworks: Use benchmarks such as UNESCO’s AI in Education guidance and the European Commission’s DigComp framework to define what AI-literate students and staff should know and be able to do at different stages. Map these to curriculum plans and CPD priorities so that AI literacy develops systematically rather than in isolated activities.

AI literacy for a new era

Artificial intelligence is increasingly part of the systems, tools and habits that shape how young people learn and live. Schools cannot choose whether students will encounter it, only how prepared they will be when they do.

AI literacy is essential. It blends technical understanding, ethical judgement, critical evaluation and purposeful application so students can use AI safely and intelligently, and staff can guide them with confidence.

This is not about chasing every new tool. It is about creating a culture where staff and students recognise how AI works, question the values and risks embedded in it, and decide when and how to use it in the service of learning. Schools can lead wisely by grounding decisions in evidence, aligning practice with values and adapting as they learn.

The strongest programmes will be deliberate and evolving in their understanding of AI. They will draw on recognised frameworks, adapt to context, promote equity in education and balance ambition with realism. Change begins with clear intent and collaborative learning, with leadership that connects curriculum, policy and professional development, and treats AI literacy as part of safeguarding, academic integrity and digital citizenship.

Schools that commit to this journey will give their communities something powerful: the ability to think clearly, act responsibly and create boldly in an AI-shaped world. This is preparation for tomorrow and an opportunity to make learning today richer, more connected and more human. The opportunity is here. Let’s take it!

AI literacy FAQs

AI literacy is the ability to understand, use and interact with artificial intelligence responsibly and safely. For teachers and students, it means knowing what AI is, where it appears in daily life and how to work with it thoughtfully, much like any other learning or digital tool.

Although some use AI literacy and AI fluency interchangeably, they are different. AI literacy is the ability to understand, use and interact with artificial intelligence responsibly and safely. AI fluency is the ability to apply AI in practice.

An AI literacy framework defines the essential skills, knowledge and attitudes students and staff need to use artificial intelligence safely and effectively. It typically covers four key areas: understanding how AI works, recognising ethical implications, developing safe usage practices, and applying critical judgement to AI outputs. A good framework provides structured progression from basic awareness to confident, purposeful use across different subjects and contexts.

Helpful Links

- What you need to know about UNESCO’s new AI competency frameworks for students and teachers

- Lyfta’s Critical Digital & Media Literacy Course

- AI Literacy Lessons for Grades 6–12 | Common Sense Education and UK version AI Literacy Lessons for Years 7-13 (UK) | Common Sense Education

- Experience AI | The excitement of AI in your classroom Raspberry Pi Foundation

- 10 Practical Activities To Embed AI Literacy In Your School Computing At School

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Skye – our AI maths tutor built by teachers – gives students personalised one-to-one lessons that address learning gaps and build confidence.

Since 2013 we’ve taught over 2 million hours of maths lessons to more than 170,000 students to help them become fluent, able mathematicians.

Explore our AI maths tutoring or find out about the AI tutor for your school.