How Schools Can Use AI To Promote Equity In Education

Equity in education has emerged as one of the key priorities for school and trust leaders, especially since the COVID pandemic, when schools recognised the true scale of digital poverty and its impact on learning outcomes. The pandemic made it clear that under-resourced children were struggling to achieve the same levels of success and understanding as their better-equipped peers.

The rise of generative AI has added another layer of complexity to these existing inequalities, potentially widening gaps further. However, when implemented thoughtfully, AI also offers new opportunities to level the playing field. As educators, there is plenty we can do.

In this article, AI bias researcher Victoria Hedlund explores the concept of equity in education, how AI can become part of the solution rather than the problem, and what successful digital and AI equity looks like in schools.

Equity in education: the distinction between equality and equity

Let’s start with acknowledging that there is no generally accepted definition of equity or equity in education.

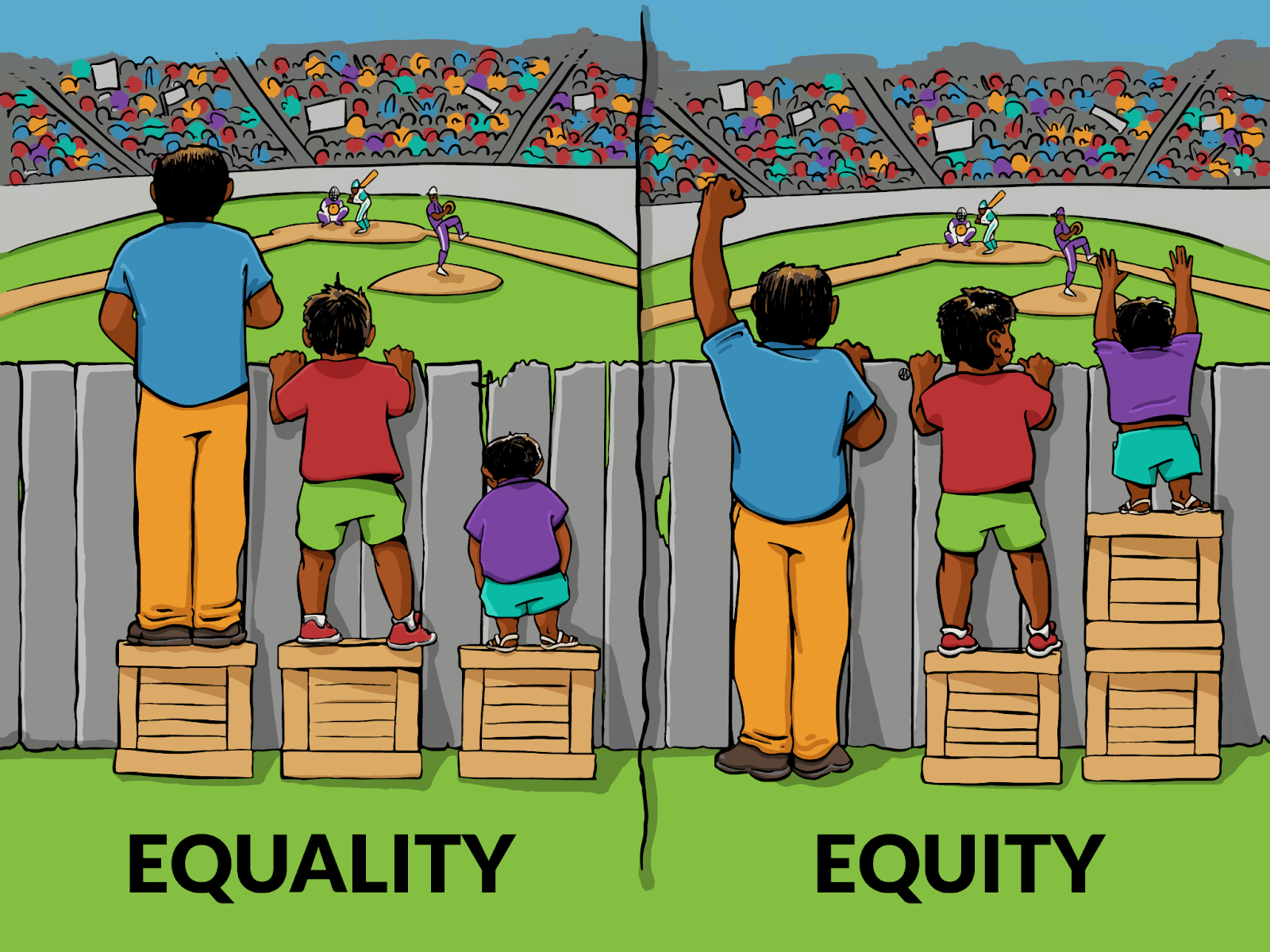

The DfE guidance shies away from using or defining equity in education, in favour of equality. The best way to think about these definitions I’ve seen comes in a visual format, through the very well-referenced image from artist Angus Maguire in the Interaction Institute for Social Change.

Equity can be thought of as a practical implementation of fairness, providing support according to need to achieve fairness of outcomes, ie more support for those who need it most.

Equality, on the other hand, giving the same provision to everyone, is not the same; being fair doesn’t necessarily mean being equal.

Equity in education is not equality; it requires addressing specific barriers faced by under-resourced and marginalised students to ensure fair opportunities for all

Discover how AI tutor, Skye, can improve your students’ confidence and maths results.

Get in touch to arrange a free AI maths tutoring session.

Try a free sessionEquity vs equality in the classroom

Imagine your school buys ChatGPT Pro access for all pupils. At first glance, this seems fair; everyone gets the same resource.

But consider two pupils:

- Child A already has this at home and knows how to use it

- Child B has no computer at home, an old hand-me-down data-free phone

How do teachers enable equity and equality in this situation?

To understand both equality and equity in education, you need to grasp two fundamentals: the difference in starting points for your pupils, and the intervention you want to execute.

Child A already understands the technology and receives support at home. Their chance of experiencing cognitive overload when using your new top-tier frontier chatbot is minimal. In fact, they may even be able to teach you a thing or two. Do they need this free access? No, because they already have it.

Child B struggles with using a PC or laptop at school, as they do not have experience with a computer at home. Their phone is used for text and calls only, as a data contract is expensive, so they also do not have access to any apps. This is a classic example of sociocultural and economic disadvantage – a key principle in equity theory in education. Do they need the free ChatGPT Pro access? In this case, of course, yes.

By giving every child in your class access to ChatGPT Pro, you may be promoting equality, but your intervention is not equitable. This is not the way to raise digital literacy for Child B.

Child B needs additional support. If not, your intervention may well have entirely the opposite outcome intended.

Without support, here’s what happens to Child B:

The cognitive overwhelm of going from next to nothing to everything is too much.

They experience disengagement due to cognitive overload and self-resentment for not being able to use the fancy new tool.

They are now demotivated and lack self-concept.

You put them in detention for off-task and disruptive behaviour (they kept pulling the keys off the keyboard and throwing them at their neighbour).

Why didn’t this intervention work? The only thing this equity approach achieves is your need to run a lunchtime detention.

Child B really needed:

- Basic computer skills training

- Step-by-step guidance on using the tool

- Small, manageable tasks where they could experience success

- Ongoing support to build confidence

True equity aims to ensure equally high outcomes for students, not just equal access to resources.

Educational equity: beyond equal access

It’s obvious that equity in education is more than devices and subscriptions. To borrow from the IT sector, educational equity means the whole support package. You need to provide ongoing support and quality aftercare.

If your programme’s not working, one of the first questions from customer support will be:

- What hardware are you using?

- Mac or PC?

- What version of Windows?

The same holds for your pupils:

- What hardware are your pupils using?

- Do they have accessibility needs?

- Do they have processing needs?

- What supports can you put in place – physical, psychological or otherwise (screen readers, visual scaffolds, dual coding)?

- What software are they using?

- Do they need your help to apply any updates?

- How can you provide this? Do they need a refresher on the basics of the environment of a PC rather than a phone?

- What support plan or pathway do you need to put in place for your pupils, and how can they (and you!) determine success along the way?

Remembering the Teachers’ Standards

You may be wondering what national policy says about equity in education and an equity approach. Interestingly, the Department for Education does not define equity. It focuses on equality, as found in the Equality Framework:

“The general equality duty sets out the equality matters that schools need to consider when making decisions that affect pupils or staff with different protected characteristics. This duty has three elements. In carrying out their functions public bodies are required to have due regard when making decisions and developing policies, to the need to: eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and other conduct that is prohibited by the Equality Act 2010; advance equality of opportunity between people who share a protected characteristic and people who do not share it; build good relations across all protected characteristics between people who share a protected characteristic and people who do not share it.”

Child B does not have any protected characteristics. What guidance is there in respect of their issues?

In fact, there’s an implied equity-based provision in the Teachers’ Standards. In particular, these standards:

- Set high expectations which inspire, motivate and challenge pupils.

- Promote good progress and outcomes by pupils.

- Adapt teaching to respond to the strengths and needs of all pupils.

These are all operationalised versions of educational equity. These are the aspects that you can work with in your classroom setting.

AI Kickstart Kit for School Leaders

Use this practical planning tool, aligned with the DfE guidance on artificial intelligence, to ask the essential questions needed when implementing new AI tools in your school. Comes with a completed example and editable AI integration planning tool.

Download Free Now!Beyond the classroom: sociocultural and economic disadvantage

Let’s return to Child A and Child B. Their narratives are deeper than the present events. The educational system has always reflected society’s divides, with disadvantaged students usually facing sociocultural and economic disadvantage.

The space we are currently in with GenAI is simply the newest version of an old pattern of longstanding educational inequalities, described by researchers as ‘structural inequality’ (OECD, 2021).

Research studies document these patterns of inequality, such as postcode, language, English being a second language and family resources, not just who owns a device, and have informed equity-based interventions in the education system.

This is why the UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence places Fairness and Non-Discrimination at the heart of responsible GenAI use. The guidance urges all AI in education to address systemic biases and power imbalances, and to ensure tools are representative of diverse populations and responsive to individual needs to enhance education and life prospects.

Cognitive science aids this equity-based approach. Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory highlights that new tools and platforms can easily overwhelm students who lack foundational knowledge or digital fluency. Without careful scaffolding, you risk disengagement, as detailed in the scenario for Child B.

So how can AI in the classroom positively impact these disparities? Or can it widen them?

The answer depends on how we use it, the support we build, and our willingness to look honestly at where students are really starting from, not just where we have decided they ‘should’ be. Equity in education, in the age of AI or otherwise, involves courage and transparency.

Without care and critical oversight, inequitable disparities and gaps between learners will widen the flaws in education.

Current educational disparities AI can address

As an AI bias researcher, I spend considerable time examining the risks of AI.

But Gen AI also has real potential to promote educational equity, especially for those who learn and communicate differently.

As someone who is neurodivergent, AI bridges vivid inner thinking and academic expression. It allows experimentation with different ways to phrase ideas and maximise engagement with those who hold different communication styles.

How AI helps me communicate

My communication style can be, and often has been, described as direct, blunt and procedural.

I do not naturally use compound noun phrases, elaborate adjectives or complex structures unless they serve an immediate purpose.

GenAI allows me to explore interpretations of my writing by placing it in different personas, such as “you are a colleague with a love of poetry” and then seeing how well my points resonate with different audiences.

This has expanded the range of people I can reach and connect with.

I think in rich visual metaphors. I have a highly creative internal “sketchpad” for images – a mental space where I can build and hold detailed visual scenes. This enables me to be a strong representational artist. Yet I cannot easily deconstruct a mental image into words that convey the depth and texture of the original.

With GenAI, I can describe an image, iterate on the description and refine it until it comes closer to the richness I see in my mind.

I am sure I am not the only person who has experienced this, who has had their communication gatekept by words. GenAI can open that gate.

The promise of AI for equity in education

An equity mindset can be defined as recognising that no two learners travel the same road. When I look at AI in schools, my research and practice focus on the unique pathway each child experiences. This includes the sequence of prompts, feedback, adjustments, and small successes or setbacks as they work with AI.

AI holds potential for tackling some of the disparities that have long been visible in our classrooms. Let’s take the case of English language learners (EAL), where AI offers targeted support to help them access and engage with the same curriculum as their peers.

- Language and cultural inclusion tools can give every learner a voice.

- AI translation services can help multilingual classrooms communicate more fluidly.

- Culturally responsive content generation and adaptation can ensure examples, metaphors, and case studies resonate with different communities.

The potential lies in the responsiveness of the tool to adapt or modify learning outcomes exactly when they’re needed. But it has to be done in an informed way, as these unique pathways can be limited by cultural bias.

Disparities can still emerge when these tools are shaped by biased training data or narrow design choices. These limitations are often most visible when AI makes normative assumptions about pupils. The risk is that existing inequities are quietly reinforced.

To overcome this cultural bias, I always focus on asking: who gets left out? Schools need tools and teams that let experienced teachers and students flag mistakes, not just accept the output. Whatever the technology, educational equity will always depend on teacher intention, reflection, and active oversight.

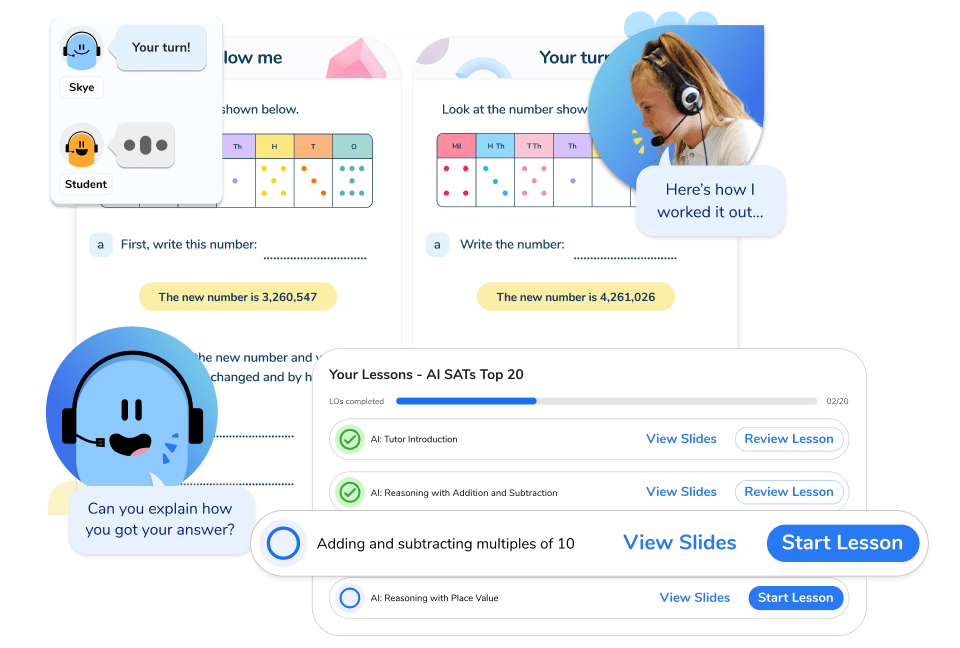

When Edtech companies start from this mindset, AI can offer real power to be equitable. Skye Third Space Learning’s AI Tutor is impressive as it keeps the management and pace with the classroom teacher, and it’s anchored in their years of human-generated teacher-created question and answer pairs. This keeps the control firmly with the human while harnessing the power of AI for the path setting, all within predefined boundaries.

Addressing bias in AI systems

Addressing bias in AI systems is critical to achieving true educational equity. If not carefully designed, AI tools can unintentionally reinforce the very disparities they are meant to overcome. This happens when AI systems are trained on data that reflects existing social or cultural factors, leading to outcomes that may disadvantage certain groups of students, especially those already facing sociocultural and economic disadvantage.

Third Space Learning is ahead of the curve with Skye, being designed from human questions, and comparing purely objective pupil answers with model teacher answers means that bias risks are minimised.

What bias looks like in practice

Bias can take several forms and varies depending on the subject. Here, we focus on issues relevant to maths teaching, Skye’s subject expertise.

Cultural assumptions in word problems

AI might consistently use examples about skiing holidays, private music lessons, or expensive restaurants when teaching percentages or money problems. Pupils from lower-income backgrounds may struggle to relate to these scenarios, making the maths feel irrelevant or exclusionary.

Language complexity

AI systems might default to complex vocabulary even when simpler alternatives exist. For instance, using “calculate the perimeter” instead of “work out the distance around” for younger pupils or EAL learners creates unnecessary barriers to understanding the mathematical concept.

Gender stereotypes in examples

AI might unconsciously perpetuate stereotypes by consistently showing boys in engineering contexts and girls in caring roles when creating word problems, potentially limiting pupils’ aspirations and engagement.

Response patterns

Some AI systems respond differently to certain names or language patterns. For example, they might provide more detailed explanations when pupils use standard English but shorter responses to pupils who use dialect or make grammatical errors, inadvertently providing inequitable support.

How to spot these issues:

- Monitor the examples your AI uses: do they reflect your pupils’ diverse backgrounds and experiences?

- Listen to how pupils respond: are some groups engaging less or seeming confused by cultural references?

- Check response quality: does the AI provide equally helpful support regardless of how pupils express themselves?

- Review progress data by demographic groups: are there patterns suggesting some pupils aren’t benefiting equally?

Creating an equitable learning environment

To create an equitable learning environment, educators, school leaders, and developers need to proactively identify and mitigate bias within AI systems. This starts with using diverse and representative data that reflect the full spectrum of student backgrounds and experiences.

Regularly testing AI tools for bias and implementing algorithms that can detect and correct unfair patterns are also key strategies.

Moreover, schools should involve teacher leaders and students in the process of evaluating AI outputs, ensuring that any issues are quickly flagged and addressed. Taking these steps helps educators ensure that AI supports, rather than hinders, the success of disadvantaged students.

Ultimately, addressing bias in AI is about creating a more equitable educational system, one where every student receives fair opportunities to achieve equally high outcomes.

6 key considerations when implementing AI: what schools need to examine

Building a fairer learning environment starts with educators themselves. To truly promote educational equity, teachers and school leaders must develop a deep understanding of the social and cultural factors that shape their students’ learning outcomes. This means reflecting on and addressing their own cultural biases, and being open to new perspectives and approaches.

- Where are you starting? Consider whether a pilot group of 10-15 pupils might help you understand how AI adapts to individual needs, but ask yourself: how will you measure what ‘benefit’ actually means?

- What does ‘designed for equity’ actually mean? While platforms may claim to allow customisation and detailed monitoring, how will you verify whether these claims work for your specific pupil populations?

- What does ‘equal benefit’ actually look like? Evaluate whether all pupils are benefiting equally from AI support. Are some groups making faster progress than others? Are there patterns in who struggles with the technology itself versus the mathematical content?

- What kind of professional development actually prepares teachers for this? While workshops and training sessions are often suggested, the reality is more complex. How do you help educators recognise bias in AI systems when the technology itself is evolving rapidly? What happens when the ‘practical strategies’ don’t work with your specific pupil populations?

- What story is your data really telling? While pathway overview tools and metrics are widely promoted as solutions, consider: Who decided what pathways matter? What biases are embedded in how these systems categorise pupil responses? Are you interpreting hesitation as confusion, or might it represent thoughtful consideration?

- Whose voices are you actually hearing? While consulting with pupils, parents, and staff sounds comprehensive, consider: Are you reaching the families who are most digitally excluded? When pupils say something ‘works,’ do they mean it’s effective or just familiar? How do you identify exclusion when those being excluded might not have the language or confidence to articulate it?

Personalised support that removes barriers

Some schools offer free data SIMs or offline AI tools for families who cannot get connected. Partnerships with local businesses or councils sometimes fill the gaps, bringing real change where budgets run out. These creative solutions and partnerships are especially crucial for supporting working-class pupils, who often face additional barriers to educational success due to socio-economic disparities.

When it comes to challenges for schools, the obvious one is AI literacy. Teachers need a sandbox environment to try things out, and a low-stakes, supportive network of peers. It’s similar for school leaders, who need to enable teachers and factor in an AI Policy.

This support can be anything from auditing the tech that you have through the plan technology for your school initiative to providing targeted CPD for your teachers. Teachers need to be able to use tools, but GenAI literacy is more than that – they need to know how they can stay in control, as they are responsible for the GenAI output in their classroom.

4 critical questions for school leaders: what equity really requires

Equity in education is larger in structure than AI, but AI can affect or create an equitable learning environment. School leaders can focus on these four key principles:

1. How can you create a genuine experimentation space? The assumption that teachers need ‘sandbox environments’ sounds reasonable, but what happens when experimentation reveals that AI responds unpredictably to different types of learners? How do you balance innovation pressure with professional responsibility?

2. What story is your data really telling? Learn about the pathway overview tools, metrics and dashboards available. These show not just whether pupils got answers right or wrong, but how they approached problems, where they hesitated, and what misconceptions emerged.

3. How do you involve all stakeholders? Consult with pupils, parents, and staff about their experiences with any AI product. What works? What feels exclusionary? What additional support do different groups need?

4. What ongoing support is needed? Schools are often told to ‘source training on AI policy and strategy,’ but who determines what constitutes adequate preparation? How do you distinguish between genuine professional development and vendor-led product training disguised as education?

An equity mindset involves an iterative, dynamic process. At the heart of all that you do, remember Child B. Prepare students and ensure they receive options for future choice, social mobility, academic success, attainment and wellbeing.

References

Department for Education (2011) Teachers’ Standards: Guidance for school leaders, school staff and governing bodies. Available at: GOV.UK (Accessed: 4 August 2025).

Department for Education (2014) The Equality Act 2010 and schools: Departmental advice for school leaders, school staff, governing bodies and local authorities. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/equality-act-2010-advice-for-schools (Accessed: 4 August 2025).

GenEd Labs (2025) GenEdLabs.ai: Ethical, inclusive and bias-aware AI for education. Available at: https://www.genedlabs.ai/ (Accessed: 4 August 2025).

Hedlund, V. (forthcoming) ‘Pathways, Prompts and Pitfalls: Recognising and Managing Bias in GenAI for Educators’, in Fitzpatrick, D. (ed.) The AI Educators Guide 2026. ThirdBox Publishing. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Educators-AI-Guide-2026-ebook/dp/B0FCMHQ8VD (Accessed: 4 August 2025).

Sweller, J. (2011) ‘Cognitive load theory’, in Mestre, J.P. and Ross, B.H. (eds.) The psychology of learning and motivation, Volume 55. London: Academic Press, pp. 37–76.

UNESCO (2021) Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. Paris: UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381137 (Accessed: 4 August 2025).