What Is A Spiral Curriculum: A Teacher’s Guide to What, How And When To Implement

A spiral curriculum is a popular model to consider when looking at how you design and enact your curriculum.

For school leaders looking to renew their focus on how to structure learning within their school, both across grades and subjects, Aidan Severs, former curriculum lead, provides a teacher and school leader perspective on the spiral curriculum to support those of you involved in developing your own high-quality curriculum and assessing all the available curriculum models and structures.

What is a spiral curriculum?

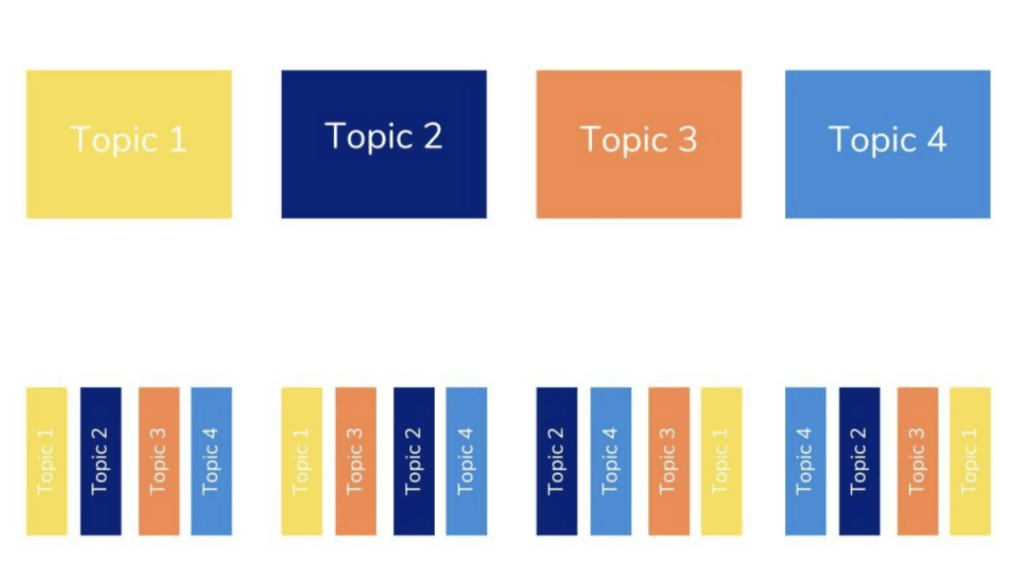

The spiral curriculum is a curriculum model in which a sequence of topics or themes are revisited in turn with the complexity of the content increasing each time learners encounter the topic or theme.

The model suggests that teachers and school leaders can see learning as an upward spiral, with foundational concepts being taught to begin with and then added to, or built upon, as the spiral loops upwards, or as prior knowledge is revisited.

Why consider a spiral curriculum

This curriculum model allows for previous learning to be reinforced as well as allowing for related new content to be taught and learned in the context of what has already been learned.

Although the concept of the spiral focuses on the revisiting of themes, it also has the sequencing of these themes at its heart. It proposes that before a learner revisits a particular theme, they may also need to have learned other content found within other themes.

Therefore, the spiral curriculum model supports the idea that a necessary part of learning is the creation of schema, or mental models, where links between material are made as the information is organized and stored in the mind of the learner.

Origins of the spiral curriculum

The spiral curriculum model was proposed and developed by Jerome Bruner, a prominent American psychologist and educational theorist, in the 1960s and was discussed in his publication entitled ‘The Process of Learning’. In it, he works with the hypothesis that “any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development” (p33). Here Bruner references the work of constructivist theorist Jean Piaget, particularly his idea that children move through four different stages of cognitive development which dictate how they learn.

The spiral curriculum in academic literature

In describing the spiral curriculum, Bruner writes: “…basic ideas… are as simple as they are powerful… to use [these basic ideas] effectively, requires a continual deepening of one’s understanding of them that comes from learning to use them in progressively more complex forms… early teaching… should be designed to teach these subjects with scrupulous intellectual honesty but with an emphasis upon the intuitive grasp of ideas and upon the use of these basic ideas. A curriculum as it develops should revisit these basic ideas repeatedly, building upon them until the student has grasped the full formal apparatus that goes with them.” (p12-13, Jerome. S. Bruner (1960) The Process of Education, Harvard University Press)

Harden and Stamper summarize that “a spiral curriculum is one in which there is an iterative revisiting of topics, subjects or themes…. A spiral curriculum is not simply the repetition of a topic taught. It requires also the deepening of it, with each successive encounter building on the previous one.” (R.M. Harden & N. Stamper (1999) What is a spiral curriculum?, Medical Teacher, 21:2, 141-143 )

Key principles of a spiral curriculum

Harden and Stamper go on to identify 4 key features of Bruner’s spiral curriculum:

Over time:

- Topics are revisited

- Levels of difficulty increase

- New learning is related to previous learning

And that as a result:

- The competence of students increases

Spiral curriculum in math

When, it comes to math, Bruner himself gives an example of how a spiral curriculum model is useful: “If the understanding of number, measure, and probability is judged crucial in the pursuit of science, then instruction in these subjects should begin as intellectually honestly and as early as possible in a manner consistent with the child’s forms of thought. Let the topics be developed and redeveloped in later grades.” (p53-54)

Spiral curriculum examples

In a spiral curriculum for math, topics like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are introduced at an early stage. As students move on to higher grades, these foundational concepts are revisited and expanded upon to include more complex topics like fractions, decimals, algebra, geometry, and calculus.

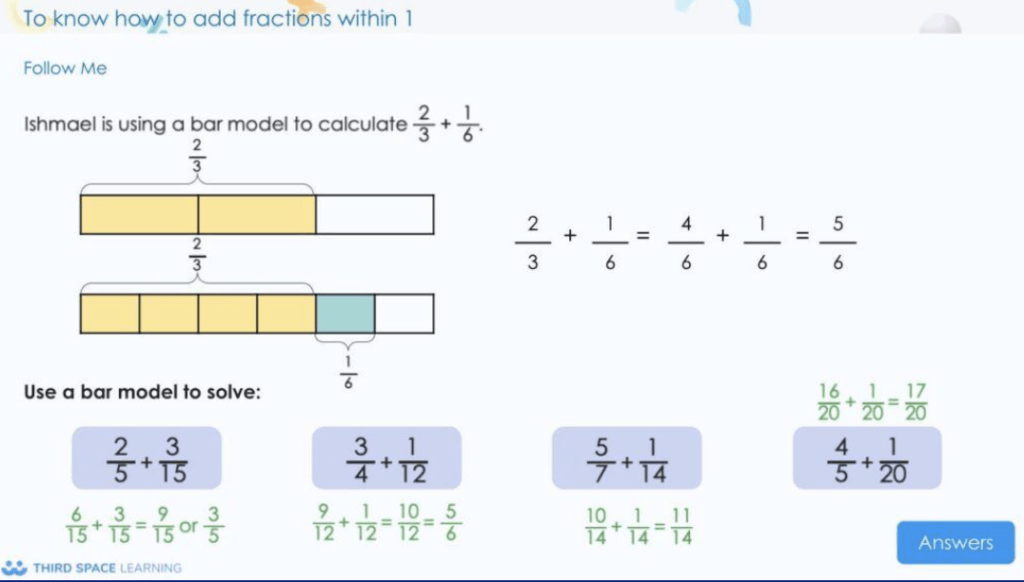

Fractions in a spiral

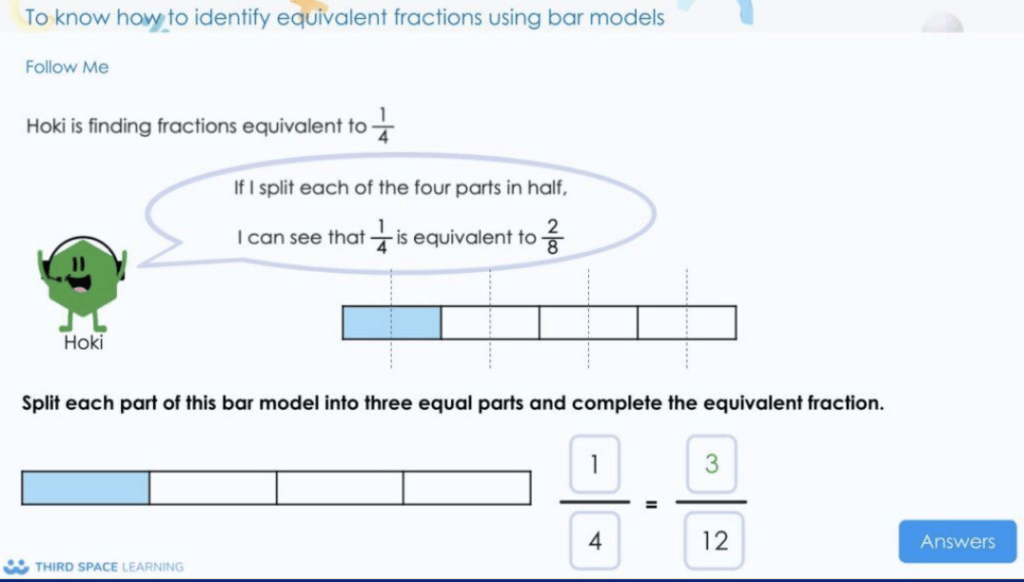

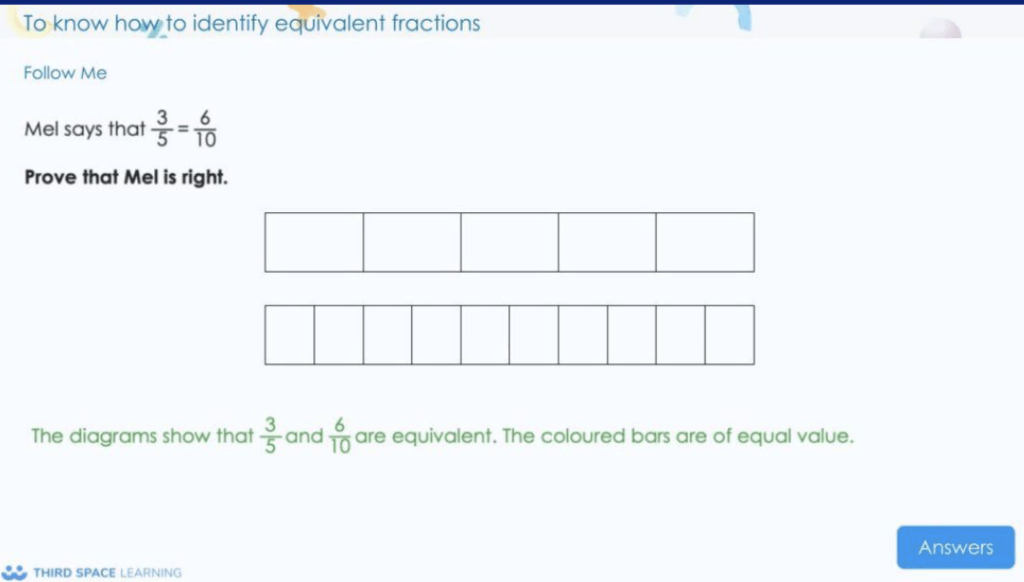

Third Space Learning’s resources build upon skills throughout the school year and are designed to reinforce past learning, ensuring that students understand the basics before diving deeper into each topic.

Let’s look at fractions as an example:

Fractions are formally introduced in 2nd grade, where children are taught to recognize, find and name a half as one of two equal parts and a quarter as one of four equal parts of an object, shape or quantity.

This is built upon with children being taught to recognize, find, name and write fractions ⅓,¼, 2/4 and ¾, of a length, shape, and set of objects or quantities.

Schools following CCSS

Fractions in 2nd grade

In 2nd grade, children learn a foundational concept: things can be split into equal parts, and when we do this, there are names for the parts created. It’s perhaps a concept that they have come across in their early years of life, however the inclusion of it in the curriculum formalizes the concept, marking it out as something that is important in mathematical thinking.

Students will partition circles and rectangles into two, three, and four equal shares. They will also begin to use the vocabulary words halves, thirds, half of, a third of, and so on. Students will recognize that equal shares of identical wholes do not have to be the same shape, and you can describe a whole as “two halves”, “three thirds”, and “four fourths”.

Fractions in 3rd grade

In third grade, students start to really develop their understanding of fractions, including representing them on a number line and finding equivalent fractions using visuals and manipulatives.

Students will expand on their knowledge of comparing numbers and fractions in 3rd grade. Students will first learn how to compare fractions with the same numerator or same denominator, using the same comparison symbols that are used when comparing whole numbers.

Fractions in 4th grade and how fractions relate to decimals

In 4th grade, students expand their knowledge of fractions and are taught to add and subtract fractions with the same denominator within one whole. This is an example of how new learning is related to previous learning, and of how the complexity increases, this time this is achieved by combining knowledge from different, previously taught topics.

When children get to fourth grade, decimals to the hundredths place are introduced alongside fractions, building on the concept that there exist numbers that aren’t whole, introducing children to another common way to represent these not-whole numbers. Children are expected to find equivalences between fractions and decimals and are also taught to carry out further addition and subtraction of fractions, this time where the answer may be more than one whole.

Fractions in 5th grade: fractions with other operations

By the time children are in 4th grade, they build on their previous knowledge of the number system, calculations, fractions and decimals, particularly focusing on equivalent fractions and converting fractions from one form to another. They also begin to multiply fractions by a whole number, having spent plenty of time in previous grades learning how to multiply whole numbers. In addition, dividing by a fraction is introduced in this grade level.

Schools not following CCSS

Other schools not following Common Core teach the same concepts as shown above, although some individual standards and concepts may vary slightly. Some concepts may be covered in different grade levels, depending on the standards your school district has adopted.

Benefits of a spiral curriculum

There are several advantages to designing and using spiral curricula:

Securing the basics and retaining knowledge

The most obvious focus is on starting with the basics, placing the emphasis on how important it is for students to grasp foundational concepts before they move on.

The fact that topics are repeated gives students the opportunity to revisit their prior learning, recalling it and using it in new ways, thus, aiding retention and leading children to a deeper conceptual understanding of the content they have been taught previously, before learning new, associated content with an increased level of complexity.

This move from simple concepts to complex concepts over time, with content linked to what is thought to be developmentally appropriate, is a key feature of the spiral curriculum approach – the benefits of this are that children are introduced to complex topics early on, but in such a way that they can understand them. In turn, doing so may help reduce student’s test anxiety if they feel they have a secure understanding of the curriculum.

An alternative curriculum model may decide that because it is so difficult to know how to multiply fractions, there is no point in teaching finding a half in 1st grade, and that children should wait until they are developmentally ready to access higher level concepts such as the multiplication of fractions before having anything to do with them.

Integrating different bodies of knowledge

A further benefit of a spiral curriculum is how topics that have been studied previously can begin to be integrated. By bringing together knowledge from different domains within the curriculum area, children are encouraged to use and apply different key concepts with a degree of fluency as they new solve problems, going beyond recall of discrete facts to an application of their knowledge and skills.

Logical sequencing

This integration is supported by another benefit of the spiral curriculum: they are logically sequenced. Spiral curriculum design recognizes, particularly in a well-structured subject like math, that as children learn more, they will need to make more connections between content in their future learning. Curricula are then designed to ensure that children are taught content in an order that begins with the simplest, most foundational concepts in each topic or domain, before introducing units of work that require the use and application of knowledge and skills from more than one of these domains.

Disadvantages of a spiral curriculum

A spiral curriculum does not fit into every context and can have limitations.

Does not translate into every subject

A spiral curriculum is better suited to some subjects than others. For example, math and science are more fact-based than others, such as art subjects which are more subjective. Although some skills in arts subjects could be seen to be introduced and built upon incrementally, it wouldn’t be the case for all the content within those subjects.

Not all learning is linear

The spiral curriculum model is based on the idea that learning is a linear process, however, it isn’t always the case. A spiral curriculum model may not be the best way to make the links between interconnected ideas within a subject, for example, how multiplication and division are commutative. If multiplication is treated as two separate topics, and are not studied as one, the curriculum is less likely to support the development of the mental models which associate the two concepts.

Can lead to misconceptions

When students are taught concepts at an age-appropriate level, it might be the case that this learning ends up being superficial because they are not yet cognitively able to grasp the nuances or full extent of the concept. Where this is the case, it may be true that later on, when topics are returned to, this superficial understanding has led to children having math misconceptions that need to be ‘unlearned’.

Gaps in time can hinder conceptual understanding

In addition to this, the number of topics inserted into a spiral curriculum may dictate the space between topics. To take our earlier example, fractions may be taught as a unit or topic once a year, resulting in children forgetting in the interim what they have previously been taught.

A spiral curriculum such as this which also has no regular review of content in the interim period between topics risks students forgetting what they were taught and teachers having to re-teach rather than remind when it comes round to teaching the topic again. When teachers have to do this, they lose time which should have been spent on teaching the new content, resulting either in teaching being rushed, or content not being taught at all.

Blocks versus interleaving

The spiral curriculum is usually blocked: topics are covered over a 2 or 3 week period, depending on the number of objectives considered to be part of that topic. Research has shown that interleaved practice, an approach in which math problems are rearranged so that practice tasks include different kinds of problems, improves mathematics learning.

When topics are taught in blocks – 3 weeks on addition for example – the kind of practice children get is blocked and they are not required to think about other kinds of problems and other areas of the math curriculum and, therefore, are not selecting solutions but simply carrying out the same procedures over and over again.

When practice is interleaved, children will be faced with problems taken from any topics that they have studied so far, thus requiring them to recall what they have learned and to choose and apply a range of strategies based on what is appropriate to the problem. Interleaved practice is not usually a feature of spiral curriculum.

An alternative curriculum model that is built upon the fact that much of the content of the math curriculum is interconnected might be preferable, although as we have seen, there are ways to use a spiral curriculum to ensure these links are being made.

For example, a spiral curriculum could conceivably teach multiplication and division as one topic, highlighting the commutativity right from the start. However it is done, a math curriculum which is rich in deliberately-made links is crucial to fluency and the usage and application of math knowledge and skills.

How can a spiral curriculum help your school?

How to introduce a spiral curriculum

It may be the case that your school’s curriculum already is developed to be a spiral curriculum.

Before developing the curriculum in your school, a good starting point would be to understand the extent to which your curriculum could be considered to be a spiral curriculum.

Developing a spiral curriculum

To develop a spiral curriculum, an intimate knowledge of the math standards used at your school will be required, as well as constant reference to it during the curricula’s creation.

Curriculum developers will be aided by the fact that most math standards already group mathematical content into topics or domains. For example, following the Common Core State Standards, the domains are: Number and operations in base 10 (place value, addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, decimals, percentages), operations and algebraic thinking, number and operations – fractions, measurement and data, and geometry (covering properties of shape and position and direction).

Curriculum developers may want to reconsider the groupings made in the math standards to ensure that concepts which are linked are not taught in isolation, however the document will provide a good starting point.

If developing a spiral curriculum, schools should bear in mind the key principles outlined above: topics should be revisited, the levels of difficulty should increase and explicit links between old and new learning should be made.

Understanding the purpose of a spiral curriculum

Just as important for curriculum developers to remember is the purpose of doing all this: to increase the competencies of the students. This should be a guiding principle for any changes made and introduced.

If you do identify ways in which your curriculum is deficient, and you think a spiral curriculum is the way forward, a significant period of development will be required. It won’t be possible to change a unit here and there, as this will have a knock-on effect later down the line. This process should involve retaining the strong elements of the previous curriculum while rearranging and strengthening the weaker aspects.

Moving between curriculum models

Any move from one curriculum to another needs to be managed with care. School leaders should consider if a wholesale move from one to another, with every child in every grade level starting on the new curriculum at the start of a new year is a wise decision.

Most curricula build on previously taught content, therefore a change of curriculum, say, in 2nd grade, may mean that a child doesn’t have requisite prior knowledge to access the prescribed 2nd-grade content, leading to teachers having to track back and teach foundational concepts, leaving them less time to teach the new content.

A simple alternative to this is to roll out the new curriculum year by year, with the youngest children starting the new curriculum each year, and the older children continuing to work on the old curriculum until eventually, the first year group to commence working with the curriculum have moved their way through the school, by which time all children will be working on the new curriculum.

Applying the curriculum in the classroom

Beyond the writing of the curriculum, one will need to consider the pedagogical approaches that will be necessary to facilitate this curriculum in the classroom. Curriculum developers should think about how the content in the curriculum will be best taught, selecting teaching practices that are well-matched to the content.

School leaders may want to consider how the curriculum and its delivery will be appropriate for children with differing needs, for example, using interventions to ensure that children have grasped the foundational concepts before moving on to learning more complex concepts.

Once this significant piece of curriculum development work is done, school leaders will need to invest in staff training and resourcing and any other necessary preparations for the delivery of the new curriculum. A curriculum on paper is all very well, but it is in the classroom where it really matters.

Communicating the reasons behind changing curriculum models

School leaders should ensure that they understand and can articulate why changes have been made to the curriculum and this should be communicated clearly to teachers and other staff members.

To get further buy-in from staff, school leaders can provide the resources that teachers need, show that they trust staff to try things out, make mistakes, and provide feedback on the new curriculum, and explain to the staff that they expect the process of implementation to take time as staff get to grips with the new curriculum. In addition to this, staff members should know how the new curriculum should be taught, with any active ingredients made very clear to them.

You may also be interested in:

- Knowledge organizers

- What Is Math Mastery? The 10 Key Principles Of Teaching For Mastery In Math

- Differentiated Instruction: 9 Differentiated Curriculum And Instruction Strategies For Teachers

- Student Centered Learning: A Teacher’s Guide

References (and quotes):

Jerome. S. Bruner (1960) The Process of Education, Harvard University Press (http://edci770.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/45494576/Bruner_Processes_of_Education.pdf)

The basic ideas that lie at the heart of all science and mathematics and the basic themes that give form to life and literature are as simple as they are powerful. To be in command of these basic ideas, to use them effectively, requires a continual deepening of one’s understanding of them that comes from learning to use them in progressively more complex forms… The early teaching of science, mathematics, social studies, and literature should be designed to teach these subjects with scrupulous intellectual honesty, but with an emphasis upon the intuitive grasp of ideas and upon the use of these basic ideas. A curriculum as it develops should revisit these basic ideas repeatedly, building upon them until the student has grasped the full formal apparatus that goes with them. (p12-13)

General claims that can be made for teaching the fundamental structure of a subject:

- understanding fundamentals makes a subject more comprehensible (p23)

- unless detail is placed into a structured pattern, it is rapidly forgotten… Detailed material is conserved in memory by the use of simplified ways of representing it (p24)… What learning general or fundamental principles does is to ensure that memory loss will not mean total loss, that what remains will permit us to reconstruct the details when needed. (p25)

- an understanding of fundamental principles and ideas, as noted earlier, appears to be the main road to adequate “transfer of training.” To understand something as a specific instance of a more general case-which is what understanding a more fundamental principle or structure means-is to have learned not only a specific thing but also a model for understanding other things like it that one may encounter. (p25)

- by constantly reexamining material taught in elementary and secondary schools for its fundamental character, one is able to narrow the gap between “advanced” knowledge and “elementary” knowledge (p26)

The curriculum of a subject should be determined by the most fundamental understanding that can be achieved of the underlying principles that give structure to that subject. Teaching specific topics or skills without making clear their context in the broader fundamental structure of a field of knowledge is uneconomical in several deep senses. In the first place, such teaching makes it exceedingly difficult for the student to generalize from what he has learned to what he will encounter later. In the second place, learning that has fallen short of a grasp of general principles has little reward in terms of intellectual excitement…Third, knowledge one has acquired without sufficient structure to tie it together is knowledge that is likely to be forgotten. An unconnected set of facts has a pitiably short half-life in memory. Organizing facts in terms of principles and ideas from which they may be inferred is the only known way of reducing the quick rate of loss of human memory. (p31-32)

R.M. Harden & N. Stamper (1999) What is a spiral curriculum?, Medical Teacher, 21:2, 141-143 (https://lchcautobio.ucsd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/R.M.-Harden-Medical-Teacher-1999.pdf)

Do you have students who need extra support in math?

Give your students more opportunities to consolidate learning and practice skills through personalized math tutoring with their own dedicated online math tutor.

Each student receives differentiated instruction designed to close their individual learning gaps, and scaffolded learning ensures every student learns at the right pace. Lessons are aligned with your state’s standards and assessments, plus you’ll receive regular reports every step of the way.

Personalized one-on-one math tutoring programs are available for:

– 2nd grade tutoring

– 3rd grade tutoring

– 4th grade tutoring

– 5th grade tutoring

– 6th grade tutoring

– 7th grade tutoring

– 8th grade tutoring

Why not learn more about how it works?

The content in this article was originally written by UK Primary Lead Practitioner Aidan Severs and has since been revised and adapted for US schools by math curriculum specialist and former elementary math teacher Christi Kulesza.