What Is Math Mastery? The 10 Key Principles Of Teaching For Mastery In Math

Math mastery, teaching for mastery in math, and the mastery approach to teaching and learning are now phrases heard all through the school system but there are still countless discrepancies about what they mean, what mastery looks like, and how to implement it.

In this article, Neil Almond takes the principles of mastery mathematics teaching as set out in Mark McCourt’s book Teaching for Mastery to provide an easy to digest primer on the 10 points every elementary and middle school teacher and school administrator should know before embarking on their ‘journey to math mastery’.

To get you started, we provide some simplified definitions before we move onto the meat of the issue – and why there are so many misconceptions around the meaning of mastery in math.

- What is math mastery?

- What is teaching for mastery?

- NCETM mastery

- Math mastery curriculums

- Who is Mark McCourt?

- 1. Teaching for mastery is an old technique, not a new one

- 2. Benjamin Bloom codified and formalized mastery teaching

- 3. There are six core elements to the teaching for mastery model

- 4. The role of the teacher in mastery teaching is paramount

- 5. Mastery teaching requires a positive relationship between the student and teacher

- 6. A conveyor-belt curriculum makes true math mastery teaching difficult to implement

- 7. All Students Can Learn Math, Given The Right Conditions And Time

- 8. Teaching for math mastery has to start from day one

- 9. An understanding of cognitive science is key to math mastery teaching

- 10. Teach everything correctly the first time

- What is math mastery?

- What is teaching for mastery?

- NCETM mastery

- Math mastery curriculums

- Who is Mark McCourt?

- 1. Teaching for mastery is an old technique, not a new one

- 2. Benjamin Bloom codified and formalized mastery teaching

- 3. There are six core elements to the teaching for mastery model

- 4. The role of the teacher in mastery teaching is paramount

- 5. Mastery teaching requires a positive relationship between the student and teacher

- 6. A conveyor-belt curriculum makes true math mastery teaching difficult to implement

- 7. All Students Can Learn Math, Given The Right Conditions And Time

- 8. Teaching for math mastery has to start from day one

- 9. An understanding of cognitive science is key to math mastery teaching

- 10. Teach everything correctly the first time

- What is math mastery?

- What is teaching for mastery?

- NCETM mastery

- Math mastery curriculums

- Who is Mark McCourt?

- 1. Teaching for mastery is an old technique, not a new one

- 2. Benjamin Bloom codified and formalized mastery teaching

- 3. There are six core elements to the teaching for mastery model

- 4. The role of the teacher in mastery teaching is paramount

- 5. Mastery teaching requires a positive relationship between the student and teacher

- 6. A conveyor-belt curriculum makes true math mastery teaching difficult to implement

- 7. All Students Can Learn Math, Given The Right Conditions And Time

- 8. Teaching for math mastery has to start from day one

- 9. An understanding of cognitive science is key to math mastery teaching

- 10. Teach everything correctly the first time

What is math mastery?

Math mastery is a teaching and learning approach that aims for students to develop deep understanding of math rather than being able to memorize key procedures or resort to rote learning.

The end goal and expectation is for all students (with very limited exceptions) to have acquired the fundamental facts and concepts of math for their grade, such that by the end of it they have achieved mastery in the math they have been taught.

At this point they are ready to move confidently on to their next stage of math.

Mastery of a mathematical concept means a child can use their knowledge of the concept to solve unfamiliar word problems, and undertake complex reasoning, using the appropriate mathematical vocabulary.

Math mastery is not a quick fix to math learning but a journey that the teacher and students go on together, with regular diagnostic assessment to check the students’ understanding and direct instruction that teaches to any gaps.

The Ultimate Guide to Problem Solving Techniques

The 9 problem solving techniques that every elementary student should know. Includes tasks for students and short explanations for teachers with questioning prompts.

Download Free Now!What is teaching for mastery?

Teaching for mastery is how the teacher (crucially with support of their school) organizes their classroom time and teaching preparation time in order for themselves and their students to go on the journey of mathematics mastery together.

NCETM mastery

NCETM, the National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics has championed the Singapore and Shanghai approach to mastery maths since the start of the new curriculum.

They have further codified it for their maths hubs training hundreds of primary maths teachers to include ‘5 big ideas in teaching for mastery’ ie

- Coherence

- Representation and Structre

- Mathematical Thinking

- Fluency

- Variation

Math mastery curriculums

There seems to have been, in the last 3 to 5 years, a resurgence of the word ‘mastery’ in educational discourse – especially around math education.

Every other mathematics curriculum advertises proudly they take a ‘mastery’ approach to math. Yet teachers’ understanding of what ‘mastery’ is seems to be limited to getting students to ‘master the content’, which doesn’t really narrow it down very much, nor does it offer any special insight beyond what we all aim to do as teachers.

In his recently released book, Teaching for Mastery, Mark McCourt gives the history and an overview of the classroom applications of the mastery model of schooling, and that is what I will be taking a closer look at in this post with particular reference to how it applies to math teaching at the elementary and middle school level.

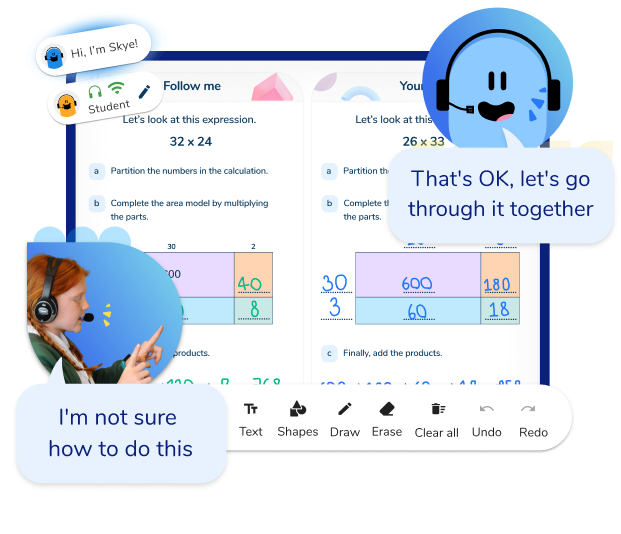

Meet Skye, the voice-based AI tutor making math success possible for every student.

Built by teachers and math experts, Skye uses the same pedagogy, curriculum and lesson structure as our traditional tutoring.

But, with more flexibility and a low cost, schools can scale online math tutoring to support every student who needs it.

Watch Skye in actionWho is Mark McCourt?

If you’re not familiar with him, Mark McCourt is a tour de force in high school mathematics education and a leading authority on the mastery models of teaching in the UK.

He has been a teacher, senior leader, headteacher and school inspector.

Mark is currently the CEO of La Salle Education, which provides professional development to schools and teachers across the UK. You can hear him speak at mathematics conferences but also on these episodes of the Mr. Barton Math podcasts:

His book, Teaching for Mastery, is subject-agnostic, meaning its principles can be applied to all subjects taught in schools but many examples focus on mastery math lessons. It’s an essential read for all math teachers, elementary, middle and high school.

Here are the ten key principles from his book

1. Teaching for mastery is an old technique, not a new one

The mastery model of teaching takes its influence from Ancient Greece and the work of Greek philosopher Aristotle (who lived approximately 2300 years ago).

The 1-to-1 tutor model, where the tutor is very much aware of the prior attainment of the students, knows where to take the learning next and, more importantly, can correct any misconceptions the student may have, is the firm foundation of the mastery approach to schooling.

This is the method that underpins Third Space Learning’s own one to one tuition math programs in school where individual misconceptions are fixed as they arise.

The tutors are trained to ensure that every student works to fully understand the math topic they are taught before moving onto the next.

The idea of teaching for mastery in a school is that you then just scale this approach up so that you get the effect of a one to one math tutor even with 30 children. Of course, this is hard to achieve in practice.

The person who pioneered this movement of aspiring to mastery teaching was Carleton Washburne in the early part of the 20th century.

2. Benjamin Bloom codified and formalized mastery teaching

In the 50s and 60s, Benjamin Bloom (yes, as in Bloom’s taxonomy) took on Washburne’s model from a similar starting point – to improve the impact of schooling on the disadvantaged where previous models didn’t.

He knew that if children were given the right amount of time to learn at their pace with appropriate conditions, then every child would be able to learn the content and master it.

Can we say the same about the math mastery model we are using to teach students math today?

Benjamin knew his model would have 2 key features:

- The crucial, successful elements of 1-to-1 tutoring, which could be transferred to a group-based environment

- The dispositions of academically and successful students in a group-based environment

Bloom noted that academically successful students used assessment as a means to improve their own understanding and not just to rank themselves against the rest of the class.

This, along with carefully designed assessment to identify misconceptions, could then be refuted and corrected by the teacher immediately.

Bloom wrote all of his work the mastery model in 1968, in a publication entitled ‘Learning for Mastery’, where he discusses elements of the mastery program, such as breaking content down into smaller units that last approximately a week or two and that frequent formative tests are used to see if the content has been mastered (Bloom, 1968).

In elementary and middle schools that follow a math mastery approach, this is now fairly standard behavior. In most schemes, not only is the content broken down into smaller units, but there are regular formative checks built in to ensure that students have grasped what’s been taught.

3. There are six core elements to the teaching for mastery model

In his book, Mark identifies six core elements of teaching for mastery from the work of Guskey (2010).

- Diagnostic pre-assessment with pre-teaching

- High-quality, group-based initial instruction

- Progress monitoring through regular formative assessment

- High-quality corrective instruction

- Second, parallel formative assessment

- Enrichment or extension activities

These same 6 elements are, therefore, the heart of a math mastery approach.

1. Diagnostic pre-assessment with pre-teaching

In the first element, careful pre-planned assessments are used to weed out any misconceptions that a student may have before a topic commences. In essence, this part of the model is to check to see if the students have the prior knowledge needed to tackle the new learning that is coming up.

Depending on the results, pre-teaching would then take place to ensure students are ready to progress onto the new idea.

For teachers to really make use of this, find questions on the same topic but for the previous grade’s objective and give those to the students before starting a new topic. Use the information from that assessment to ensure appropriate pre-teaching for those who will need it.

Read also: Your Math Intervention Must Have – Formative Diagnostic Assessment

2. High-quality, group-based initial instruction

In the second element, mastery models ‘emphasize the importance of engaging all students in high-quality, developmentally appropriate, research-based instruction in the general education classroom’ (Guskey, 2010) to ensure the maximum chance of success for the students.

Read also: Explicit Instruction and Worked Examples in Primary Math

3. Progress monitoring through regular formative assessment

In element three, regular formative assessment takes place to elicit an understanding of what has been taught already i.e. to ensure the intent from the second element has been understood.

Students would be expected to answer questions directed to them by the teacher and complete mini-quizzes, for example. Teachers would act on this information and provide immediate feedback as necessary.

Read also: The Difference Between Formative And Summative Assessment

4. High-quality corrective instruction

The fourth element refers to the teachers’ actions when they have learned that a student has not grasped an idea. This is not the same as reteaching what you have taught the same way.

The knowledgeable teacher would be expected to draw on their vast pedagogical and didactic knowledge to present the content in another way that the student could understand.

Guskey (2010) writes, ‘for a unit of a week or two in length, for example, corrective instruction might last one or two days.’ However, this time is later recovered as students are well versed in all prior topics.

The elementary and middle school math teacher must be able to draw on visuals, manipulatives and a variety of metaphors and examples so that the student has the best chance of understanding the topic.

Read also: Common Math Misconceptions and How To Overcome Them

5. Second, parallel formative assessment

In the fifth element, we continue the cycle of teaching and check for understanding as a result of changes brought in at the fourth element. An important feature of the mastery model is that this is not the final assessment of this topic.

Mark draws on the analogy of driving. If you do not pass, the cycle of learning and practice continues until you have mastered the content.

6. Enrichment or extension activities

The final element is to provide challenging enrichment activities that provide a valuable learning experience but, crucially, does not move them on to new mathematical ideas – it may look at previously taught ones.

While those that have passed the assessment of the unit move on to this, those that fail will continue to receive corrective instruction until they pass.

It is important that the content provided here is additional material that not everyone needs to access.

Math leads in schools should make clear to their teaching teams, and to their students, which content is required for all students to know and which is additional in-depth enrichment that can be given to those who master a mathematical concept quicker than others.

4. The role of the teacher in mastery teaching is paramount

Despite Carleton’s early influence of the educational philosopher Dewey, it was the work done by psychologist Fred. S Keller in adapting behaviorists’ ideas into educational resources that allowed students to study at their own pace with minimal instruction from a teacher (which were being developed at the same time Bloom was looking at the work on mastery).

Both Carleton and Bloom appreciated the crucial role of the teacher in the mastery model.

As in the Aristotelian one to one tutor method, in order for the student to be successful, the tutee needed an experienced and knowledgeable tutor.

From the six elements of the mastery model, you can see how the teacher plays a key role in each section:

- The teacher will design or locate appropriate pre-assessment activities that will clearly demonstrate specific misconceptions that the expert teacher can correct in real time.

- The teacher will deliver the first and second wave of high-quality instruction, but also know countless ways of explaining different ideas so that all learners have the greatest opportunity to succeed.

Mastery teaching doesn’t begin the moment you get your teaching certificate

In the book, Mark challenges the idea that after you’ve got your teaching certificate, we are all expert educators.

He argues that all learners go through the continuum of novice to experts, with training of teachers early in their career spending time on the superficial, usually asking themselves things such as:

- What am I saying?

- How long should I do this for?

- What should I do next?

Eventually, teachers progress through the novice/expert continuum where the focus is on strategic knowledge – lessons learned from teaching to get better. Mark states that this process can take around 10 years of teaching mathematics.

This is certainly the case when learning how to properly administer math mastery, as well as other subjects within the curriculum.

All teachers need to know that they can always improve and become more effective. School leaders and administrators should look to see what the best professional development they can offer to their staff is.

Particular focus should be on the didactics of math teaching, for example, the use of math manipulatives.

This should be followed up continuously and not as a box-ticking exercise.

Read more

- What Metacognition Looks Like At Elementary School: 7 Steps for Implementation

- Quality First Teaching: What It is And How To Make The Most Of It

- 21 Best Math Challenges To Stretch Your Most Able Students

5. Mastery teaching requires a positive relationship between the student and teacher

Learning is a social event and for the students to have some buy-in to the mastery model of schooling, they need to have confidence and faith in the teacher delivering the content.

They need to know that the teachers are the holders of this knowledge and that they deem it important enough for the students to know.

As Mark says, ‘In order to accept new knowledge as truth, the people first must believe that the teacher is a carrier of truth and is sincere in their desire for the student to become learned.’

We know that in order for learning to happen, students must attend to and think about what is happening – this will only happen when those positive relationships have been developed. To get a mastery model of teaching, you need to get behavior right too!

While it may seem tempting to get the ball rolling quickly at the start of August, take the time in your primary classroom to embed routines, especially those relating to math tasks, like getting whiteboards and pens out and giving out and taking up manipulatives.

The time spent doing this and embedding these behaviors at the start of the year will pay dividends for the remainder of it and give you much more time for learning.

Read also: Why You Should Follow Mastery In Math: 6 Real Benefits

6. A conveyor-belt curriculum makes true math mastery teaching difficult to implement

So far, I imagine nothing that has been said here is controversial or that new to teachers, yet to achieve a mastery model of schooling in our current system is impossible to replicate due to one reason – grades.

Mark McCourt is very skeptical of what he calls ‘Conveyor-belt Curriculums’ which is the type of curriculum that is currently used in the US.

This approach is when content is delivered to learners based around age and grade level expectations.

A 1st grade child will automatically progress to 2nd grade – and the content that comes with it – despite them not grasping the 1st grade content.

The conveyor-belt cannot be stopped as teachers need to progress ‘through the curriculum.’ What then often happens is that learners are left floundering with the new ideas from the new content or are removed from other lessons to have interventions.

In the mastery math model for schools – in its true sense – learners must understand all the content that has come before advancing to the new stages. Therefore, truly achieving the mastery model is impossible given the constraints of the curriculum from the government.

We can, therefore, only use principles from a mastery program to inform our pedagogical thinking to fit the current conveyor-belt system that we find ourselves working in.

The best that can be done would be to create highly homogeneous groups of students with a narrow achievement gap and start the mastery math model with them.

Teachers currently teaching with mixed ability grouping in math may want to review or discuss with the rest of your team whether this is the best approach.

7. All Students Can Learn Math, Given The Right Conditions And Time

Linked to the idea above comes another answer to what is teaching for mastery.

It is the most powerful and important idea of the model – that given the appropriate time and conditions, ALL students can learn the content!

Time is one of the most precious resources teachers have; it is imperative that we spend this resource as wisely as possible. Mastery is not to be seen as a detailed curriculum that labels a unit with a grade level, or week number or a lesson number.

If you hold onto the belief that learning can take place within the time confinements of one lesson of one hour in length or that ‘progress’ can be shown within minutes of students arriving in the classroom then you cannot claim to be implementing the mastery model.

The mastery model moves from the question of ‘Have I taught the curriculum?’ to ‘Has the curriculum been learned?’

The right conditions would be seen as the student/teacher relationship and the pedagogical and didactic choices that the teacher would employ when embarking on the second element of the mastery model – high-quality grouped instruction.

What else is clear in his book, is the role the student plays in their own learning. Another point central to the mastery approach is that of effort. The student is expected to put a lot of effort in to achieve what the teacher has promised they will learn.

School leaders and administrators need to ensure that there is a culture in your elementary and middle schools that students need to give their full effort to everything that they try and, while they may not be successful the first time, if they keep at it they will be. For some schools, this may already be embedded as part of a culture of growth mindset.

Teachers need to ensure they create the right conditions. They do this by making sure they use the time given to them wisely and plan appropriate interventions to ensure any missing background knowledge is learned, using strategies for differentiation in the classroom that seek to ensure the raising up of as many students as possible.

8. Teaching for math mastery has to start from day one

For the mastery-model to be truly effective and sustaining, it has to start from day one – kindergarten.

The only way that it could work through elementary school would be through a rigorous and well-structured plan – that could take up to 2 to 3 years- and a tremendous amount of professional development opportunities for staff.

As Mark puts it, ‘Training should focus on ensuring that a subject teacher has multiple approaches for every concept they will be required to teach. This becomes the profession’s body of knowledge. The canon of how to teach.’

It is therefore not sufficient for a school to decide late in the summer semester that there will be a change of teaching model to the mastery model and this is to be expected to occur across all grades with only two professional development days to support it.

It should be a rolling program (that is, it begins in kindergarten and goes up with that year group) with each grade level receiving as much professional development as required for the model to be successful.

There are many benefits to math mastery being the initial program of teaching for mastery that you introduce into your elementary school. Math lends itself well to this mastery approach due to its more structured nature in comparison to some other school subjects.

9. An understanding of cognitive science is key to math mastery teaching

The aim of the mastery model is to ensure that all learners have understood and remembered what has been taught.

To give us the best chance of this happening, it is important to draw on the canon of knowledge that cognitive science has given us over the last 50 years and implement this in our instructional phases.

While there is not enough time to go into all the detail, the key elements of cognitive science that teachers should be aware of in their math mastery teaching are as follows:

- Working memory/Long-term memory

- Cognitive load theory and the various effects that come with that

- Schemas

- Retrieval and the testing effect

- Desirable difficulties – spacing, interleaving

- The hypercorrection effect

- Learning vs performance

Many of these topics are covered in Craig Barton’s book, How I Wish I’d Taught Math, which Third Space has covered in a series of blogs on teaching math for elementary school teachers by Clare Sealy. Start with this one on Cognitive Load Theory.

By having an understanding of the above, teachers can really begin to think about the choices that they make in the classroom in regards to explicit instruction and the way they deliver their main teaching in a way that will promote learning for long-term retention.

10. Teach everything correctly the first time

Finally, if you’re looking for a one sentence answer to achieving math mastery through the mastery model of teaching, it’s quite simple: teach everything right the first time.

Where teachers have to rush through to complete the curriculum, tricks or sometimes lies are often used to cover that content quickly, such as telling children in 1st grade that you cannot take 8 away from 6, or steps are skipped, such as rote learning multiplication facts without exploring the relationships between them.

Mark argues that this creates two problems.

First, it breaks down the relationship between the students and the teacher, as the teacher is exposed as a liar and therefore not a person to be trusted. The suggested course of action here is to tell the student it is possible, and that this will be covered when we look at another type of subtraction.

Secondly, it does not improve a learners mathematical understanding. Mark makes the case that teachers should be taught in the didactics of math – the technical detail – so that from the very beginning, we are getting things right for the learners in our care.

By doing this we help them develop mathematical fluency and reasoning skills, both of which are key to helping them become better as mathematicians and in their problem solving.

Pedagogy is not enough.

It is only through the careful selection of pedagogy and knowledge of multiple didactic choices will we allow students to see the interconnectedness of mathematical ideas.

We should not see math as a set of procedures to learn and a curriculum to get through, but rather see it as a journey to understand the universe we are in (according to Mark there are 320 mathematical ideas to learn to know the body of math).

These should be taught correctly the first time so that everyone can understand them and be part of the conversation.

Mathematics mastery teaching and learning may be a long procedure, but it is one that is certainly worth the effort you will be putting in to get there.

Sources of Inspiration

McCourt, M (2019). Teaching for Mastery. Woodbridge: John Catt Education

Bloom, B. S. (1968). Learning for Mastery. Instruction and Curriculum. Regional Education Laboratory for the Carolinas and Virginia, Topical Papers and Reprints, Number 1. Evaluation Comment . Washington, D.C., USA: Office of Education.

Guskey, Thomas. (2010). Lessons of Mastery Learning. Educational leadership: journal of the Department of Supervision and Curriculum Development, N.E.A. 68. 52-57.

Do you have students who need extra support in math?

Give your students more opportunities to consolidate learning and practice skills through personalized math tutoring with their own dedicated online math tutor.

Each student receives differentiated instruction designed to close their individual learning gaps, and scaffolded learning ensures every student learns at the right pace. Lessons are aligned with your state’s standards and assessments, plus you’ll receive regular reports every step of the way.

Personalized one-on-one math tutoring programs are available for:

– 2nd grade tutoring

– 3rd grade tutoring

– 4th grade tutoring

– 5th grade tutoring

– 6th grade tutoring

– 7th grade tutoring

– 8th grade tutoring

Why not learn more about how it works?

Meet Skye, our AI voice tutor. Built on over a decade of tutoring expertise, Skye uses the same proven pedagogy and curriculum as our traditional tutoring to close learning gaps and accelerate progress. Watch a clip of Skye’s AI math tutoring in action.

The content in this article was originally written by primary school lead teacher Neil Almond and has since been revised and adapted for US schools by elementary math teacher Christi Kulesza.