AI Literacy in Schools: A Practical Guide for Teachers and Leaders

For centuries, schools have focused on helping young people to read, write, and work with numbers. Today, another core skill is becoming just as important: AI literacy. The ability to understand and work with digital tools, specifically AI technologies, is shaping how students learn, how teachers teach, and the skills that will be needed in future jobs.

AI is already part of daily life in education, from the tools students use to research and create, to the systems that organize lessons and manage assessment. Yet many encounters with artificial intelligence happen informally and without guidance. Schools that take a deliberate approach to AI literacy skills can help staff and students to use these tools with more clarity and confidence.

This guide sets out what AI literacy means in practice, why it matters for elementary, middle and high school education, and how schools can start and continue to promote AI literacy. It offers a balanced view of opportunities and risks, and provides practical steps for teachers, school leaders, and policy makers who want to integrate AI literacy into their curriculum, culture, and digital strategy.

Book a free AI math tutoring pilot for up to 20 of your students.

See how unlimited one-on-one high-dosage math tutoring can support your school or district and boost students’ math achievement.

Developed by math teachers, trusted by 4,100+ schools, and counting.

Book a free pilotReading, Writing, Arithmetic… and Algorithms: What is AI literacy, and why does it matter?

AI literacy is the ability to understand, use, and interact with artificial intelligence responsibly and safely. Corporations across industries are offering AI courses and professional development programs to get today’s adults up to speed, and education is no exception.

For both teachers and students, AI literacy means knowing what AI is, where it appears in daily life, and how to work with it thoughtfully, much like any other education technology.

An effective AI literacy framework in educational settings brings together four key elements:

- Understanding: Being able to differentiate between generative AI, predictive models, and other forms of AI to understand their functions, what it can and cannot do, how outputs are produced, and where they appear in everyday tasks.

- Ethics: Recognizing that every AI model reflects human choices and values, and exploring fairness, privacy, and the consequences of design decisions.

- Safe use: Making informed decisions based on data about which AI tools are appropriate, protecting personal data, and recognizing risks such as bias or misinformation.

- Judgment: Asking questions of AI, checking information, and critically evaluating outputs.

These skills are now essential for education across all ages, from K-12 to higher education and college students. Generative AI tools, language translation services, and artificial intelligence-enabled classroom platforms are already part of learning and daily life. Without structured teaching, students’ first generative AI use often happens without guidance or awareness. Therefore, AI literacy education should begin as early as elementary school to prepare students for future challenges.

Promote AI literacy in schools

AI now appears in many parts of school life, though often in quiet, unplanned ways. A student might test a homework helper to check a concept, experiment with an image generator for an art project, or use a translation tool to understand a text. These moments can be useful, but they can also raise questions about accuracy, bias, and safety. Without shared understanding, experiences of AI can be inconsistent. AI needs human expertise, skills and knowledge.

Some teachers have begun to explore AI technologies for planning, feedback, or generating lesson ideas, discovering where they can support creativity or free time for other priorities. Many schools have even started to explore AI tutoring. Others are more cautious of AI adoption, watching developments while considering the right moment to start. Both positions are reasonable in a period of rapid change.

Curriculum references to AI vary. Computer science classes may introduce algorithms and data, and social studies or advisory periods might cover online safety, but opportunities to practice critical use of AI are still rare. Embedding these skills in existing subjects could make them part of everyday learning rather than a separate activity.

AI policy work is ongoing. Many safeguarding and IT guidelines were created before current generative AI technologies became widely available, so leaders are reviewing how these apply to today’s tools and contexts, as well as how frameworks can adapt to rapid AI development.

Understanding these varied starting points helps schools decide how to move forward. AI literacy frameworks can grow steadily, shaped by the school’s own values, priorities, and pace.

Math Intervention Checklist

Essential step-by-step checklist to help you select, manage and evaluate the best math intervention programs for your students

Download Free Now!The role of AI literacy

AI literacy sits at the intersection of technical knowledge, critical thinking, and digital citizenship. A strong literacy framework defines the skills and knowledge, attitudes, and safeguards that protect students and prepare them for a future where AI is part of not only teaching and learning, but also life.

For teachers, AI literacy skills strengthen professional confidence, helping them use AI tools where they add value and to anticipate potential risks to wellbeing or academic integrity.

For school leaders, it supports choices based on data about resources, policy, and communication with parents.

5 core components of AI literacy in teaching and learning

AI literacy in schools is not just knowing that a tool exists or how to operate it. It is the gradual development of skills, attitudes, and safeguards that help students use AI in the classroom in ways that are safe, thoughtful, and purposeful.

1. Understand how AI works

Students benefit from a basic understanding of what artificial intelligence technologies and computing systems do, how they process data, and where their limitations lie. This is less about coding expertise and more about recognizing that AI cannot think like a human or do what educators do, that it works only with the data it has, and that its outputs can be incomplete or incorrect. This understanding helps learners question results and draw on their human skills to evaluate and edit outputs when necessary, rather than accepting them uncritically.

2. Recognize ethical and social impacts

3. Develop safe and critical use

AI literacy includes knowing how to protect personal data, avoid unsafe applications, and check the reliability of AI-generated content as AI models can “hallucinate” outputs that are inaccurate. Students can learn to recognize signs of bias or misinformation and know when to involve a trusted adult if something feels wrong.

4. Apply AI purposefully

Used well, AI tools in education can support tasks such as generating ideas, refining drafts, testing hypotheses, or exploring different perspectives. The emphasis is on improving thinking, not replacing it, so students remain active participants in the learning process where AI is simply another resource for learning.

5. Embed wellbeing, safeguarding and citizenship

AI literacy connects closely to digital citizenship. It includes making choices based on data about technology use, participating respectfully in online communities, and maintaining a healthy balance between on-screen and offline life.

When introduced gradually, revisited often, and linked to real learning scenarios, these components can help students and staff develop the knowledge and judgment needed to engage with AI effectively and confidently in both education and everyday life.

5 practical starting points for schools to develop an AI literacy framework

Integrating AI literacy into teaching and learning does not require a fully formed program from day one. A series of small, deliberate steps can build confidence for staff and students, while giving leaders the insight to develop AI literacy initiatives to suit their context.

1. Audit what is already happening

Stay updated on which AI tools educators, school staff and students use. This can reveal where effective practice is taking place, as well as highlight tools that may not meet safeguarding or curriculum needs.An audit can also uncover background uses of AI, such as translation or automated feedback, that influence learning without always being visible.

2. Link to recognized frameworks

Draw on existing guidance from trusted sources. The OECD and UNESCO offer AI literacy frameworks that set out the knowledge and skills learners need. Referencing these helps ensure your approach aligns with leading international experts and can make it easier to explain priorities to staff, school board members, and parents.

3. Provide space for Professional Development

Education leaders and teachers need time and support to effectively develop their understanding of AI. They should be allowed time and space to explore AI-enabled tools in a safe, low-pressure setting. This could take the form of short professional development sessions, peer workshops, or subject-based discussions. Direct interaction is the most effective way to understand AI capabilities and limitations.

Encouraging staff to share examples of effective learning scenarios can help improve basic knowledge, confidence, and spark new ideas, as well as increase engagement among less confident computer users. It’s important to remember that AI literacy requires digital literacy as a prerequisite and all staff should be supported with this.

4. Use safe, age-appropriate tools

Select AI tools with strong privacy protections and suitability for the age group.In elementary education, that might mean using guided environments with clear prompts and structured discussion. At the high school level, a wider range of tools may be possible, but still with oversight to ensure they serve the learning purpose.

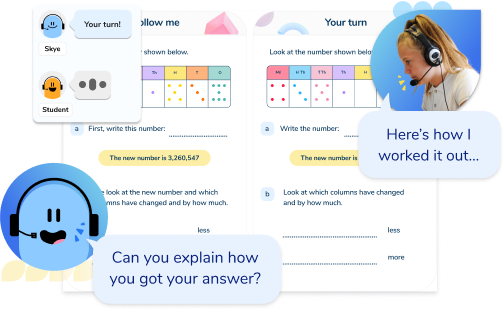

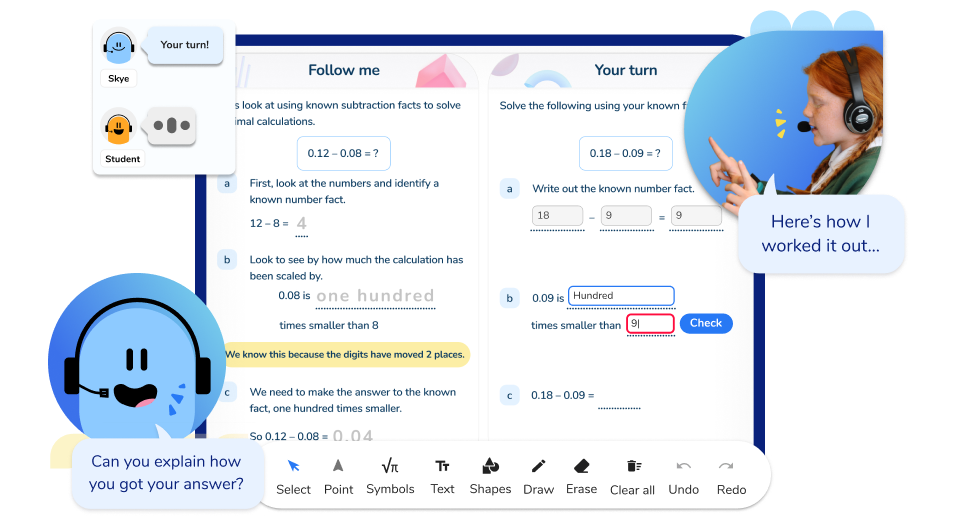

Skye, the age-appropriate AI math tutoring tool

Hundreds of schools across the country are implementing AI tutoring with AI math tutor, Skye. With unlimited sessions for unlimited students, schools can provide access for every student who needs additional support to secure their understanding of Grade 3-8 math content.

Skye, the spoken AI tutor, uses age-appropriate, curriculum-aligned lessons designed by our team of math experts and former teachers. It adapts to the pace of each individual to provide personalized math help that closes learning gaps and accelerates math progress.

A recent study by Educate Ventures Research found that students receiving tutoring from Skye improved their accuracy from 34% to 92% within a session.

Read about 5 use cases for how schools like yours are using AI tutoring.

5. Identify curriculum touchpoints

Leading with purpose: policy, culture, and what ‘good’ AI use looks like

Strong AI literacy begins with leadership that treats it as part of the school’s long-term vision for safeguarding, teaching and learning. It is not simply about keeping pace with emerging technologies, but about ensuring staff and students can work with AI safely, thoughtfully, and in ways that reflect the school’s values.

Develop clear, adaptable policies

AI policies should give staff and students clarity on expectations while leaving space to continue developing AI literacy. Policies need to address the following with examples relevant to everyday classroom practice:

- ethical use

- data privacy

- academic integrity

AI in schools guidance from the Office of Educational Technology (OET) and State Boards of Education can provide a baseline, while OECD and UNESCO frameworks can help define the knowledge and skills expected of AI-literate students.

Embed AI literacy across school life

When AI literacy is included in educators’ professional development, curriculum planning, and pastoral work, it becomes part of the school’s culture. Education leaders can encourage each subject area to consider the potential benefits and risks of AI in their discipline, and to revisit AI literacy as part of ongoing professional development. This reinforces the idea that AI literacy grows over time, through regular attention and shared responsibility.

Define and share a vision of excellence

A shared understanding of what ‘good’ looks like can guide decisions and help measure progress. This might include:

- Ethical and safe practices embedded in everyday teaching

- Staff with the technical knowledge to use AI-enabled tools appropriately

- Students able to contribute to policy through structured feedback by critically evaluating their use of AI

- A clear literacy framework understood by staff, students, and parents

Connect leadership to safeguarding and innovation

AI literacy is part of protecting students as well as preparing learners for the future. Safeguarding policies should cover AI systems in the same way they cover other digital technologies, while also encouraging safe, creative engagement with AI in learning scenarios.

Make policy visible in practice

Policies have the most impact when they are reflected in day-to-day routines. Consistent language from staff, classes and presentations exploring AI’s role in society, and subject leaders sharing examples of effective prompts can all help build a culture where AI literacy is simply part of how the school operates. Before long, AI will start to feel like Wi-Fi and computers, part of the normal way of operating.

Responding to 5 common concerns about artificial intelligence

Leaders and teachers are carrying real pressure. Time is tight. Expectations from parents and students are high. The world and society are moving very fast. Our aim here is reassurance with substance, so that you can make choices based on data and teach with confidence.

AI raises practical and ethical questions for schools. Addressing them directly helps staff feel confident and ensures students learn safe, purposeful use.

1. “Students know more than we do”

Many students encounter AI before teachers do, but familiarity and engagement is not the same as judgment. The “digital native” label is misleading and unhelpful. Teachers set the boundaries, choose the context, and guide exploration.Scenario-based discussions work well: students analyze AI outputs against agreed criteria such as accuracy, bias, and relevance, then reflect on what worked and why. This allows peer learning while keeping professional authority at the center.

2. “AI undermines creativity or rigor”

Well-designed tasks make AI a starting point, not the finished product. In English, students might compare two AI-generated openings for a persuasive speech, then adapt them for a target audience. In Geography, they could assess AI-suggested hypotheses for fieldwork.Recording prompts, annotating drafts, and explaining improvements ensures creativity and rigor remain with the learner.

3. “It is too soon, or too uncertain”

Delaying action leaves AI use to happen unseen. Start small with a short pilot in one or two subjects, set clear boundaries, measure impact, and adapt. Protect data privacy, avoid under-13 accounts, and safeguard assessment integrity. Begin with trusted guidance and add context-specific expectations.

4. “Using AI is affecting how students think”

Over-reliance on AI can weaken critical thinking. Short routines such as comparing AI-generated summaries with trusted sources, or reviewing AI-provided math solutions step by step, help students evaluate rather than accept. Make clear when AI is off-limits for mastery tasks and deep learning and when it is permitted for exploration, always with evidence of process.

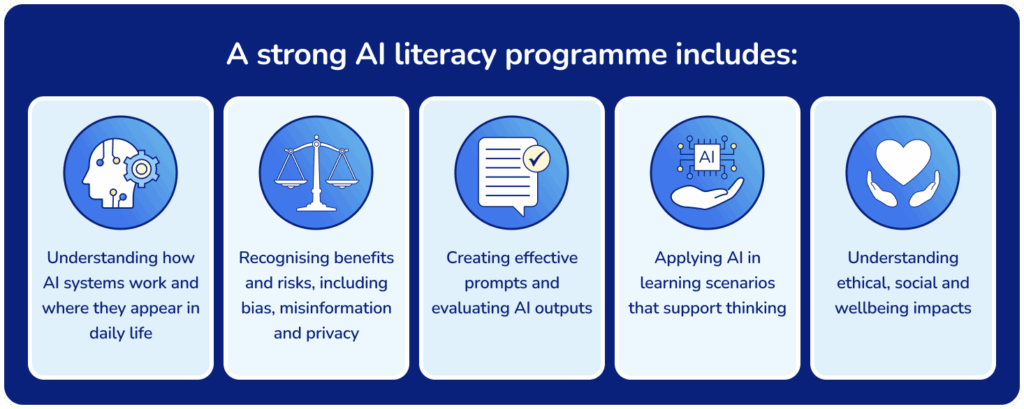

5. “We are not clear on what skills to teach”

A strong AI literacy program includes:

- Understanding how AI systems work and where they appear in daily life

- Recognizing benefits and risks, including bias, misinformation, and privacyCreating effective prompts and evaluating AI outputs

- Applying AI in learning scenarios that support thinking

- Understanding ethical, social, and wellbeing impacts

Staff need parallel knowledge plus the skills to select tools, embed AI literacy into the curriculum, recognize misuse, and model safe, purposeful use.

6 practical steps for leaders that help right now

1. Set classroom norms for safe, purposeful use

Agree on when AI tools may be opened, how prompts are recorded, and how outputs are checked. Require students to paste any prompt into their notes to build traceability and support coaching over time.

2. Teach effective prompts as part of literacy

Show students how to give purpose, constraints, and sources. For example:

- Purpose: draft a balanced summary for a 7th Grade audience.

- Constraints: 150 words, plain language, one benefit, one risk, two sources to check. This keeps AI in service of the task and supports choices based on data.

3. Protect assessment while allowing practice

For coursework, require planning artifacts, annotated drafts, and a short oral exam. For homework, alternate AI-permitted tasks with AI-free tasks, making expectations visible in the brief.

4. Use a simple, repeatable risk screening process

Before introducing an AI tool, check:

- Purpose: Is it aligned with curriculum or pastoral goals, and can it promote AI literacy?

- Data: What is collected, where stored, and who can access it? Does it meet privacy requirements?

- Age suitability: Is it appropriate and safe for the age group?

- Control: Can functions be limited to prevent unsafe use?

- Impact on learning: Does it encourage critical thinking and creativity rather than over-reliance?

5. Offer quick, regular Professional Development

6. Bring parents with you

Provide a short guide explaining AI literacy, where it appears in the curriculum, and homework rules. Include three conversation starters families can use at home to build shared understanding.

Handled in this way, AI tools become part of a wider culture of curiosity and care. Teachers retain control of the learning process, students develop skills for safe, thoughtful use, and leaders can grow AI literacy initiatives that feel realistic and grounded in school values.

What the experts say on AI literacy: insights from research and practice

AI is not neutral: Professor Wayne Holmes

Holmes’ work with UNESCO shows that every artificial intelligence system reflects the data, values, and priorities of the people and organizations that created it. He warns that treating AI as an impartial helper hides how bias, power, and commercial interest shape its outputs.

For schools, this means AI literacy must include explicit teaching on how to question emerging technologies’ origins, purpose, and likely limitations. Leaders should also ensure that policies address ethics and governance, not just functionality.

Co-design matters: Professor Judy Robertson

Robertson’s research on computing education and the “Data Education in Schools” program demonstrates that involving students in designing and critiquing AI projects deepens their understanding far more than passive use.

Professor Judy Robertson advocates giving young people authentic problem solving opportunities using AI tools, combined with structured teacher guidance. This builds transferable skills in critical thinking, collaboration, and ethical reasoning, and ensures AI literacy is rooted in purposeful, age-appropriate tasks.

Speculative thinking is vital: Professor Jen Ross

Ross’ work on digital futures in education focuses on asking “what kind of future do we want with AI?” rather than only “how does AI work?”. Her methods use structured activities where students and staff imagine near-term and longer-term scenarios for AI in their subject, weighing potential benefits and potential risks.

A futures-oriented approach makes values and priorities visible, helping schools align AI literacy with their broader vision for education.

What schools can take from this

- Treat AI as value-laden, not neutral: Teach students to identify whose goals and values are embedded in AI systems, using case studies and tool comparisons. Apply the same scrutiny when selecting tools for school use.

- Integrate co-design into learning: Build AI literacy initiatives around real-world problem solving projects where students and staff work together to plan, test, and evaluate AI use. Include explicit discussion of ethics, bias, and reliability at each stage.

- Use futures thinking to keep purpose in view: Run regular, structured scenario-building exercises that encourage reflection on AI’s role in different subjects and contexts. Compare these visions to current practice and adapt policy accordingly.

- Connect practice to recognized frameworks: Use benchmarks such as UNESCO’s AI in Education guidance to define what AI-literate students and staff should know and be able to do at different stages. Map these to curriculum plans and professional development priorities so that AI literacy develops systematically rather than in isolated activities.

AI literacy for a new era

Artificial intelligence is increasingly part of the systems, tools, and habits that shape how young people learn and live. Schools cannot choose whether students will encounter it, only how prepared they will be when they do.

AI literacy is essential. It blends technical understanding, ethical judgment, critical evaluation, and purposeful application so students can use AI safely and intelligently, and educators can guide them with confidence.

This is not about chasing every new tool. It is about creating a culture where staff and students recognize how AI works, question the values and risks embedded in it, and decide when and how to use it in the service of learning. Schools can lead wisely by grounding decisions in evidence, aligning practice with values, and adapting as they learn.

The strongest programs will be deliberate and evolving in their understanding of AI. They will draw on recognized frameworks, adapt to context, promote equity in education, and balance ambition with realism. Change begins with clear intent and collaborative learning, with leadership that connects curriculum, policy, and professional development, and treats AI literacy as part of safeguarding, academic integrity, and digital citizenship.

Schools that commit to this will give their communities something powerful: the ability to think clearly, act responsibly, and create boldly in an AI-shaped world. This is preparation for tomorrow and an opportunity to make learning today richer, more connected, and more human. The opportunity is here. Let’s take it!

AI tools, professional development resources and helpful links

- What you need to know about UNESCO’s new AI competency frameworks for students and teachers

- AI Literacy Lessons for Grades 6–12 | Common Sense Education

- The Day of AI program developed by MIT provides short-form AI literacy curricula for educators teaching students aged 5 to 18.

- Foundational courses in AI include Google AI Essentials, AI For Everyone by DeepLearning.AI, and Microsoft’s AI-900 Certification.

- Companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and Intel are offering free AI courses and learning resources online to enhance workforce AI literacy.

- IBM offers online courses and resources to help individuals improve their AI literacy skills.

AI literacy FAQs

AI literacy is the ability to understand, use, and interact with various technologies integrating artificial intelligence responsibly and safely. For teachers and students, it means knowing what AI is, where it appears in daily life, and how to work with it thoughtfully, much like any other learning or digital tool.

Although some use AI literacy and AI fluency interchangeably, they are different. AI literacy is the ability to understand, use, and interact with artificial intelligence responsibly and safely. AI fluency is the ability to apply AI in practice.

An AI literacy framework defines the essential skills, knowledge, and attitudes students and staff need to use artificial intelligence safely and effectively. It typically covers four key areas: understanding how AI works, recognizing ethical implications, developing safe usage practices, and applying critical judgment to AI outputs. A good framework provides structured progression from basic awareness to confident, purposeful use across different subjects and contexts.

Do you have students who need extra support in math?

Skye – our AI math tutor built by experienced teachers – provides students with personalized one-on-one, spoken instruction that helps them master concepts, close skill gaps, and gain confidence.

Since 2013, we’ve delivered over 2 million hours of math lessons to more than 170,000 students, guiding them toward higher math achievement.

Discover how our AI math tutoring can boost student success, or see how our math programs can support your school’s goals:

– 3rd grade tutoring

– 4th grade tutoring

– 5th grade tutoring

– 6th grade tutoring

– 7th grade tutoring

– 8th grade tutoring