How To Write Multiple Choice Questions: What We’ve Learnt From Analysing 24,916 Multiple Choice Maths Questions and Answers

Writing multiple-choice questions (MCQs) may seem to be a relatively simple process – write a question, choose some reasonably plausible answers and call it a day.

But a truly worthwhile MCQ must not only be carefully prepared to cover a range of outcomes, but be constantly monitored and analysed to judge its effectiveness and usefulness for the people it’s written for.

At Third Space Learning we’re always striving to provide the best learning experience for our maths intervention pupils, and designing an effective multiple choice question is part and parcel of that goal.

This blog explores how exactly we manage to do that; how we design, analyse and redesign our questions to be as impactful as possible.

The science behind our question designs

Research carried out by universities and e-learning specialists suggest that there are several important rules an MCQ should contain to be adequate for any learner.

As the Centre for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo suggested, ‘Well-designed MCQs allow testing for a wide breadth of content and objectives and provide an objective measurement of student ability’.

This is backed up by Dr Cynthia Brame from the Centre for Teaching at Vanderbilt University who suggests that MCQs have an advantage over other types of testing because of their:

- versatility, as they can assess various levels of learning outcomes

- reliability, as they are less susceptible to guessing than true/false questions,

- validity, as they can typically focus on a relatively broad representation of material with students usually able to answer questions more quickly than some other types of tests.

The Ultimate Guide to Effective Maths Interventions

Find out how to plan, manage, and teach one to one (and small group) maths interventions to raise attainment.

Download Free Now!The rules a good MCQ should follow include:

- They should test comprehension and critical thinking, not just recall knowledge.

- They should use simple sentence structure and precise wording.

- Most of the words should be in the question stem, rather than the answers.

- All distractors should be plausible, a similar length and be presented in a logical order.

- The order of correct answers should be mixed.

- They should be mutually exclusive (no trick questions) and if possible avoid double negatives.

- Keep the number of answers consistent, between 3 to 5.

While most of this research is centred around using MCQs with university-level students, a lot of these rules are useful when designing MCQs to be used by primary school children – the principles remain the same, even as the content changes.

At Third Space our thinking focuses on the children we will be testing; we adapt our questions to suit their age and ability, as well as providing opportunities for them to have to use more skills than simply recalling answers.

Third Space Learning’s design philosophy

At TSL, we have a meticulous writing, marking and analysis process, so that every MCQ we use is suitable for the type of learner it’s aimed at. This is particularly important considering their purpose; we use MCQs to evaluate pupil learning at both the start and end of a lesson.

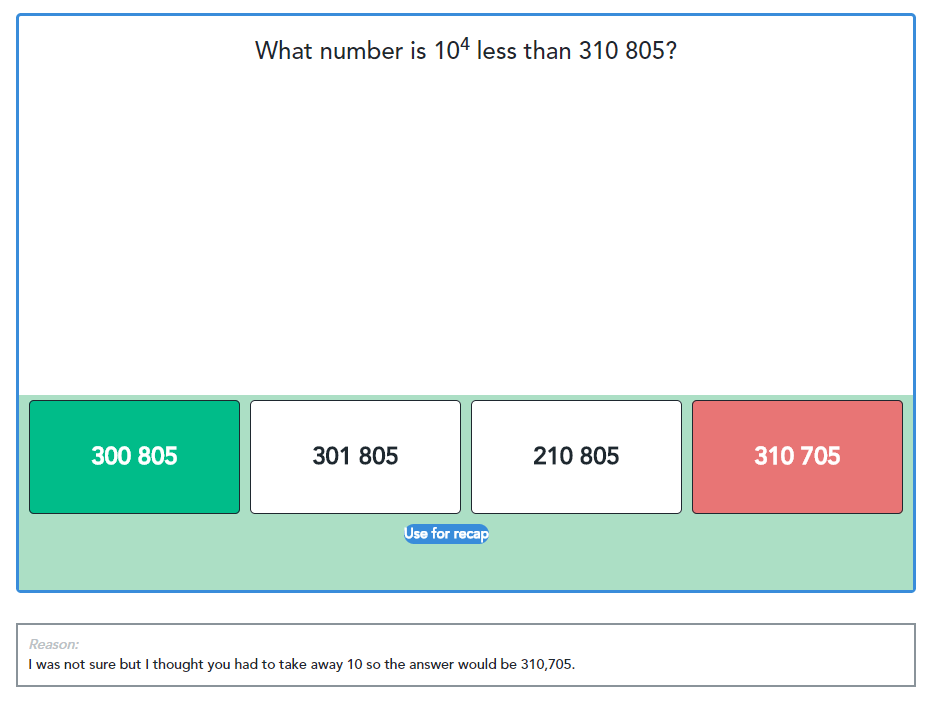

Above is an example of one of our MCQs. It has been designed to be used after the relevant lesson (in this case ‘Counting in powers of 10 up to one million’) has been completed.

It consists of a short and easy to understand question stem, followed by 4 plausible options for the pupil to choose from.

These options are all ones that challenge the pupil to remember what they have been taught, especially the meaning behind ’10 to the power of’.

One of the options has switched digits around to confuse the pupil, whilst the remaining three have all been reduced by a power of 10.

The colours show the correct answer (marked green) and the incorrect answer chosen by the pupil (marked red).

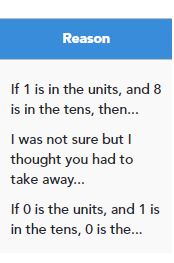

The pupil has also given a reason for their choice, which shows the tutor that the pupil has not mastered what was taught in the lesson; although they have understood that the 310 805 has been reduced by a power of ten, they haven’t grasped what is meant by the indices.

As the tutor may well decide to use this question as a warm-up in the following lesson to revise this topic, they can use the handy ‘Use for recap’ button to save and insert it into the next session they have with the pupil.

This feature allows tutors to quickly make use of previous questions pupils have attempted for a variety of reasons, from revising topics they haven’t understood to testing whether they have mastered an area they seem to know well.

Designing ‘at scale’

A tutor might draw conclusions from an answer like this for use with that particular pupil, but that’s not the only value we can gain from it.

This answer is just one of hundreds or even thousands for that same question, from other pupil attempting it in different parts of their own learning journeys.

Our content creation team frequently conduct their own analysis of pupil responses to questions like these, the conclusions of which they use to modify those questions for greater effectiveness.

We can undertake this sort of analysis because of our reach (we’ve delivered over 673,000 lessons to almost 57,000 pupils since our founding) and the size of our question bank – we’ve created 6,229 MCQs, each with 4 possible answers for a total of 24,916 possible responses. Given that each pupil will answer 3-5 MCQs per lesson, this broadens the scope of potential responses out even further.

With such a large potential database of pupil responses – a database that grows larger every day – our team can pull apart every aspect of a question to measure its impact. When they then make changes to that question, they do so with the confidence that their decisions are data driven.

For example, the layout, fonts and sizes of the question above have also been carefully thought out, as it is important that the question and distractors are easy for children to understand. Enough spare space has also been provided that the pupil can write down their attempts to work the question out.

These have to be consistent amongst all the questions, as constant changes to the font or size may confuse pupils and increase cognitive load. Learn more about cognitive load theory in the classroom here.

How we use and analyse our MCQs

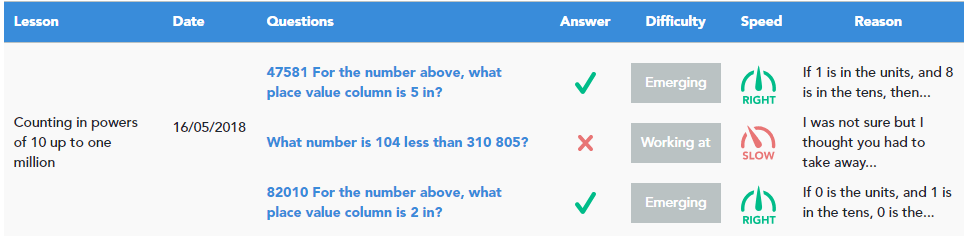

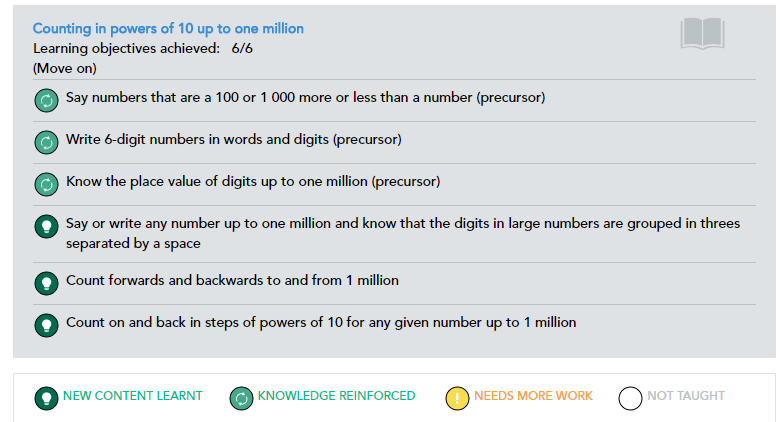

The picture above shows an example of a pupil’s results page from our online platform, which can be seen by the tutor after the pupil has attempted the MCQs. Some basic information related to the questions is visible, namely:

- the lesson they relate to

- the date they were attempted

- the questions themselves and whether the pupil got them wrong or right

However, it is the additional contextualised data that truly gives the tutor the ‘magic bullet’ to understand what is really going on with this particular pupil. Let’s elaborate on the following three aspects:

- difficulty rating

- speed of answering questions

- reasons given by the pupil for their answer

to help you understand how our tutors and content team use them as diagnostic tools to adapt and personalise learning for each pupil.

Difficulty rating

A question can be at one of three levels: ‘Emerging’, ‘Working at’ or ‘Extension’

- ‘Emerging’ questions are basic questions that are precursors to what’s been taught in the lesson

- ‘Working at’ questions test what has been taught in the lesson

- ‘Extension’ questions are more challenging questions that put what has been taught in the lesson into various contexts

When delivering questions, the system adapts to how the pupil is doing, as the ‘results’ screen shows.

The child got the first ‘Emerging’ question correct, so it next gave them a slightly more difficult ‘Working at’ question.

However, because the pupil got this one wrong, the system gave them another ‘Emerging’ question, judging that the ‘Working at’ questions may not be suitable for this pupil at this point.

How it benefits tutors:

A tutor can then use this information to understand at which level the pupil is struggling.

If it is at the ‘Emerging’ knowledge level, then they will spend more time focusing on the basics, as the tutor can judge whether the pupil has some gaps in their prior knowledge that need to be plugged.

If it is at the ‘Extension’ level, then they know where that pupil needs to be stretched and perhaps that they need to revise the topic in real life contexts.

In this example, as this is a ‘Working at’ level question the tutor knows that the lack of understanding relates to a learning objective in the lesson they’ve just taught, and so can go back and evaluate that learning objective and see how to go over it again in a fresh way so that it is mastered by the pupil.

How we use it at scale:

How the difficulty of the questions affects pupils’ understanding is important not only to the tutors but also to the content creators.

If a question is being consistently got wrong by large numbers of pupils, then it may well be at the wrong level and therefore must either be changed to a new level, or amended so it is suitable for ‘Working at’.

What to do with this sort of question will depend on its level.

For example with a seemingly tricky ‘Emerging’ question, it is more likely that there is an error in the language or distractors that needs to be corrected, rather than the question being pitched at the wrong level.

Speed of answering question

This gives an idea of how quickly the pupil is answering the question and how much time they are spending thinking about it.

The speed is shown by the position of the dial, the words ‘slow’, ‘right’ and ‘fast’, and the colours green and red, which all indicate how much time the pupil spent on the question.

How it benefits tutors:

In the above example, we can see that the pupil answered the two emerging questions in the correct amount of time, neither taking too long nor rushing through them.

However, for the question the pupil got wrong the report shows that the child spent too much time on it, indicating this with the red slow dial.

The tutor can see that the pupil spent a lot of time trying to work out what the question was asking them to do and trying to remember how to do it, reinforcing to the tutor that further work is required.

How we use it at scale:

For our content creators, the speed at which pupils attempt a question is vital to seeing how effective it is.

If pupils are taking a long time with a question then it suggests that there is a problem with it, whether that be unclear language, wrong level or some mistake confusing pupils; they then know the question needs to be changed.

If pupils are not spending a long time on a question which consistently comes up as ‘fast’ then perhaps the question is too easy for that level and needs to be moved to another level or made more challenging, depending on who the question is being targeted at.

The report could also show that pupils are guessing the answer to a question rather than trying to work it out, indicating that perhaps the question needs an adjustment to the language or distractors.

Reasons given by the pupil

In this exemplar case, the pupil was able to answer questions on areas they’d learnt previously but got the question incorrect that related to what was taught in that day’s lesson.

When analysed with the reasons the pupil has given for each of their answers, the tutor can see that the pupil may not have fully understood one of the objectives of the lesson.

The Speed column backs this data up, showing that they answered the two ‘Emerging’ questions in the right time, but obviously took a long time with the ‘Working at’ one.

How it benefits tutors:

Just as importantly, the reasons they give and the time spent on each question give us indicators to more nuanced measures of growth, such as perseverance, grit, effort and confidence in their abilities (especially obvious if they have guessed many of the answers).

As one of Third Space Learning’s key objectives is to help children improve their growth mindset and confidence in themselves, these results help us see where the pupil is following that lesson, and lets the tutor decide how much revision is needed to help the child master that topic.

The pupil’s reasoning may show that they have no confidence with this area, that they have a misconception that needs to be addressed or that they do not fully understand why they have given their answer and just guessed.

The tutor’s decision is further aided by the data about each learning objective in the lesson.

These are the learning objectives for the lesson the pupil answered MCQs on, for which you’ll remember there were two ‘Emerging’ and one ‘Working at’.

Comparing these learning objectives to the results, the tutor can see that the question the pupil got wrong related to the learning objective on ‘Counting on and back in steps of powers of 10 for any given number up to 1 million’.

As this was new content to the pupil, the tutor can see that some further revision is needed to master this, but not as much as if it was something they had learnt before.

Also, the tutor has assessed that this learning objective was met during the lesson itself, although not enough to allow the pupil to independently answer questions on it correctly; a recap at the beginning of the next lesson may well be all the pupil needs to master this.

How we use it at scale:

For content creators, the reason given by a pupil helps give an understanding of why the pupil got the answer they gave, and how the set-up and language of the question may have affected them.

In this example, the pupil has understood from the words ‘less than’ that they needed to take away, but not how much they needed to take away. This indicates that rather than the language of the question being unclear, a lack of understanding led to the incorrect answer.

We can also gauge the pupil’s use of mathematical words and how their confidence in using this language is improving, and their reasoning for their answers (proving that they know not only the answer, but how they worked it out and why it is correct).

Pupil reasoning is one of the most important factors in effective question design – obtaining pupil feedback can clarify any doubts you might have about how a question ought to be changed (or not changed).

Read more: How to Measure Pupil Attitude and Mindset in Maths

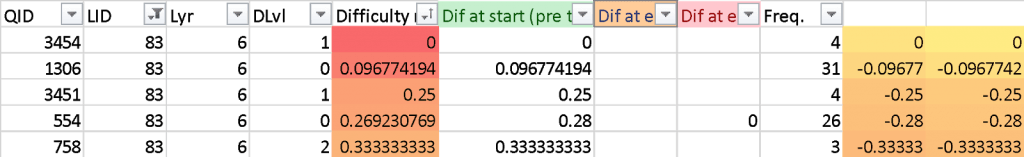

How we analyse the MCQs

This example of our data analysis shows how our system analyses the questions, giving detail as to what level each question is, the number of pupils attempting them, and how often they got the question correct at various stages of the teaching process.

The final overall score shows whether more or less pupils are getting it wrong or right.

This level of detail means the content writers can see the questions that are causing most difficulty and then go and correct them, the results of which will be seen in future analysis.

This excerpt from an analysis spreadsheet shows the ID of the questions and lesson, the year they are used with and the difficulty level.

But just as importantly, it shows how often the questions were attempted and how often the questions were answered correctly, whether at the start of a lesson, end of a lesson or end of a unit.

The overall ratings show how the results have changed over time, further enhanced by use of different colours.

The way it’s been set up gives the content creators the ability to easily see which questions are ‘under-performing’ and causing pupils most difficulty. They can then target those questions, going into each individually and making changes to whatever is causing so many incorrect results.

Even if a question is being answered correctly most of the time, that may indicate that it is at the wrong level or too easy to understand, and therefore also needs to be changed. So green may sometimes be as wrong as red!

As you can clearly see, every step a pupil makes when they work with us is constantly assessed and analysed, from the first time the pupil answers the question.

We look at the results in many ways, so a clear overall picture is given to both the tutor and the content creators as to why questions were answered the way they were.

This means the tutors can nurture the pupil’s mathematical knowledge alongside their growth mindset and overall confidence level. At the same time the content writers can judge every question they write, correcting and amending any they feel are incorrect or inappropriate for the high quality we strive to attain.

Interested in finding out more about how Third Space Learning’s maths intervention programmes could benefit your school? Call 0203 771 0095, or try a free demo today!

Further Reading:

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Every week Third Space Learning’s maths specialist tutors support thousands of students across hundreds of schools with weekly maths tuition designed to plug gaps and boost progress.

Since 2013 these personalised one to one lessons have helped over 150,000 primary and secondary students become more confident, able mathematicians.

Learn about our experience with schools or request a personalised quote for your school to speak to us about your school’s needs and how we can help.